Explore This Topic

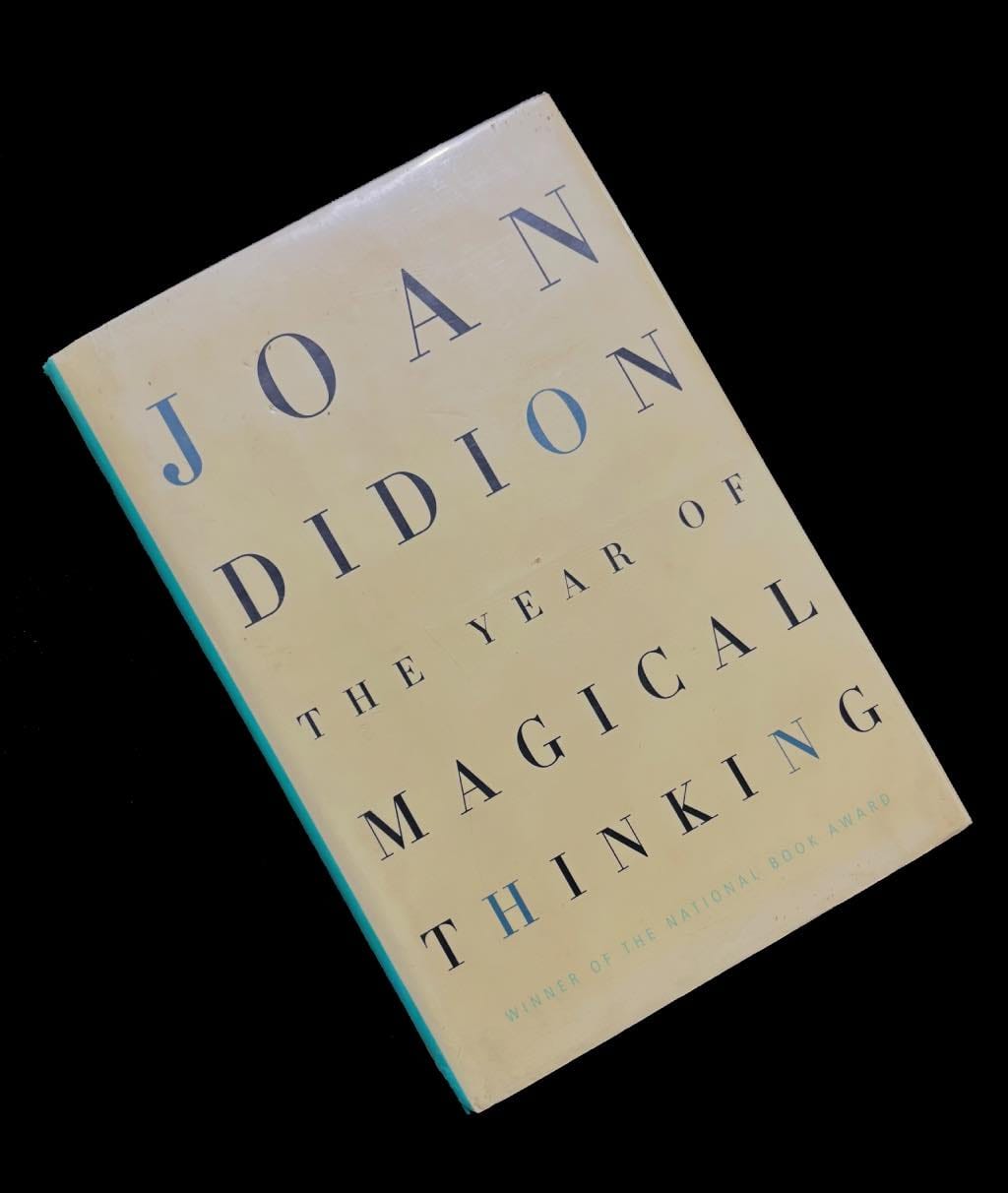

- The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion: A Deep Literary Analysis

- Why Joan Didion’s Prose Style Works in The Year of Magical Thinking

- Grief, Memory, and Magical Thinking: Themes in Didion’s Work

- 8 Striking Quotes from The Year of Magical Thinking (And What They Reveal)

- Books Like The Year of Magical Thinking: Grief Memoirs That Go Deeper

- What Didion Doesn’t Say: The Historical Context Behind The Year of Magical Thinking

Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking (2005) is often classified as a memoir, but to call it simply a memoir is to flatten a work that redefines the very form of personal narrative. Before this book, Didion had already established herself as a precision stylist, recognized for her cool detachment, psychological insight, and sharp journalistic control. But this book is something else entirely. It marked a shift in the literary memoir, expanding it beyond recollection into a mode of writing that mirrors the psychological or emotional complexity of actual experience.

Here, Didion does not sentimentalize; she dissects. This book is not just an account of grief but an inquiry into how language fails us when we are most in need of it, obeying grief’s rhythm rather than narrative convention. Didion wrote the book after the sudden death of her husband, John Gregory Dunne, while their daughter, Quintana Roo, was critically ill. It is an unflinching attempt to capture the mental disarray that follows profound loss.

This article offers a comprehensive analysis of The Year of Magical Thinking as a literary work, not only in content, but also in structure, style, and cultural position. We investigate how Didion’s syntax and disjointed prose reflect psychological confusion, and explore the interplay of themes such as magical thinking, memory, and denial. The article also connects to supporting pieces that analyze her prose, dissect her use of language, unpack her most piercing lines, and trace the book’s lasting influence on contemporary writing about grief.

Form as Grief: How Structure Reflects Psychological Breakdown

What distinguishes this work is not just its subject, but how it embodies the fractured experience of it. Didion uses repetition, temporal disruption, and linguistic precision to simulate the disorder of mourning. The book’s structure mirrors the unpredictability of thought; she circles back, contradicts herself, replays events, and redacts memories. It evades the luxury of tidy closure and instead offers the reader an exposed consciousness, struggling to order an incomprehensible reality while simultaneously rejecting its finality.

The moment of John’s death, for instance, recurs throughout the book. Didion circles back to it obsessively, not to analyze but because her mind compulsively replays it. The suddenness and unrehearsed cessation of a domestic routine (“You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends”) remains fixed, avoiding narrative absorption. She does not seek to explain why it happened, only to capture how impossible it feels that it did.

This refusal to follow a linear arc sharply distinguishes the book from conventional memoirs. Where many grief narratives build toward healing, reconciliation, or philosophical acceptance, Didion constructs a personal account that consciously avoids closure. She does not emerge transformed because the writing remains trapped in the cognitive pattern of grief: doubling back, holding out against finality while disrupting any clean structure.

The book’s structure does not simply function as a container for grief; it is grief as it behaves in real time, a mirror of Didion’s mind under duress. Time collapses inward while past and present blur. She describes events that happened weeks apart in adjacent sentences, then interrupts herself with medical records, quotations, and annotations. Just as grief confuses chronology and memory, the book avoids traditional literary structures and instead focuses on tracing back a story that disregards linearity.

Didion’s Language and Prose Style

Didion’s prose is often described as spare, but in Magical Thinking, it is more than that; it is clinically exacting. Her sentences are stripped of ornament not for effect, but because anything else would feel dishonest. Because of this, the tone of the book has often been mistaken for detachment.

But what Didion accomplishes in this book is not simply coldness. Even at her most devastated, her syntax remains composed. The declarative sentences come one after another, as if she is testing the strength of facts. “I remember thinking that I needed to discuss this with John,” she writes. “There was nothing I did not discuss with John.” The repetition is childlike in its rhythm and obsessive in its insistence. She is not building an argument but trying to hold fragments of comprehension altogether.

Her control over voice is all the more startling given the subject matter. The book contains almost no metaphors. Her vocabulary avoids sentiment as she writes in a tone closer to report than confession. When she describes her husband’s sudden death, she does not linger in emotion but instead gives the details: they sit down to dinner; she turned her head; he fell. The horror lies in the understatement; by withholding expression, she forces the reader into the psychological gap where grief operates.

As repetition becomes a defining characteristic, phrases recur—“the ordinary instant,” “the night he died,” “I needed to discuss this with John”—as though the act of writing cannot progress without re-encountering what has already happened. This is not redundancy but the very essence of the book’s architecture, wherein these repeated lines function like refrains in a poem, anchoring the text in emotional loops that mirror the interior experience of loss.

For a focused breakdown of how Didion uses repetition and sentence rhythm to mimic cognitive patterns, see: Why Joan Didion’s Prose Style Works in The Year of Magical Thinking.

Magical Thinking, Memory, and Denial: Thematic Refractions

Didion does not grieve conventionally. She grieves by thinking. However, the thinking she describes is not philosophical contemplation. It is magical, marked by its refusal to surrender to fact. She documents with exacting detail the rituals that attempt to suspend reality. She cannot part with her husband’s shoes because he might come back. She combs through medical records not to understand what happened, but to discover some overlooked version where he survives. Her grief is obsessive. It is a logic so airtight it begins to hollow out from within. She knows he is dead, and yet she cannot believe it. The phrase “magical thinking” is the precise clinical term for the state she inhabits.

In this logic, memory is not a solace but a trap. She circles the past aimlessly, caught in repeating loops. Moments replay compulsively, such as the dinner table, the fall, the ambulance, and the hospital, not for their insight but for their unanswered nature. Memory deceives as much as it recalls; it alters, contradicts, corrects. Didion recounts earlier statements only to revise them later. The mind, she suggests, functions as an editor: selective, unstable, and always in flux.

Denial in this book is not a passing stage but a condition that underwrites the entire structure. Her grief does not erupt in breakdowns or catharsis but takes the form of contradiction. “I knew he was dead,” she writes, “but I didn’t believe it.” This is not irony. It is the core of her narration. She performs the motions of understanding through research, writing, and medical inquiry, but comprehension remains out of reach. The thinking appears logical, even lucid, yet it persistently evades conclusion. This is what gives the prose its tension: an argument that cannot convince its own author.

These themes do not stand apart but refract through one another. Magical thinking distorts memory; memory undermines reality; denial gives the entire account its rhythm. What Didion renders is not the experience of grief as feeling, but its architecture: circular, intellectually charged, and incapable of tidy ending.

For a full thematic exploration, including connections to Didion’s broader body of work, see: Grief, Memory, and Magical Thinking in Didion’s Work.

Grief in Fragments: A Close Look at Key Quotes

Some of Didion’s most striking lines are not elevated pronouncements. They arrive discreetly, almost unguarded. Yet their effect accumulates gradually, line by line and image by image, until the page becomes an emotional pressure point. These moments are open-ended; they are shards that return to the mind when narrative fails. Each sentence acts as a structural anchor, a point the text builds on and circles back to.

Sentences That Distill Loss

“Life changes fast. Life changes in the instant. You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends.”

The opening line of the book delivers impact without offering a ramp or introduction. The rhythm of the first two sentences, with their repetition and clipped phrasing, enacts the very disorientation Didion is about to explore. Then, she turns sharply: a dinner table, the most banal of settings. That last line grounds the abstraction in real life, revealing the instability of everything we trust as stable.

“The ordinary instant.”

A phrase so stripped down to its core it could be overlooked, but this is Didion’s thesis. Death doesn’t always arrive with warning but disrupts an otherwise unremarkable moment, and in doing so, permanently alters our understanding of time. In a book that repeatedly breaks linearity, this phrase names the illusion it’s responding to: that anything about life is safe or predictable.

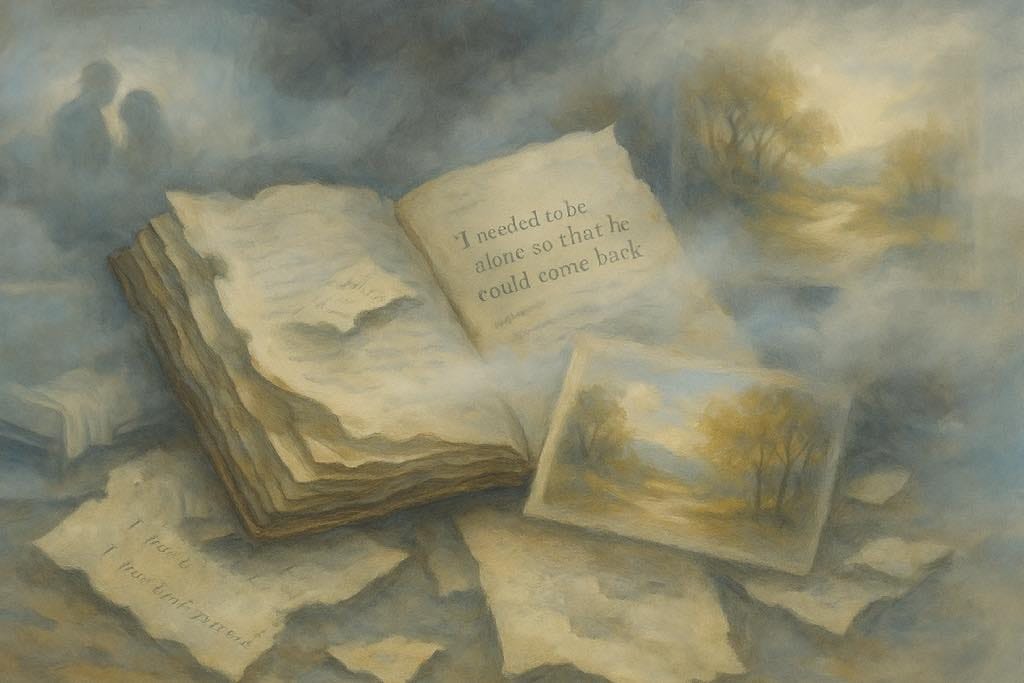

Quiet Surrealism, Reluctant Belief

“I needed to be alone so that he could come back.”

This is the moment when Didion names her magical thinking, with the line hovering between clarity and hallucination. The syntax is measured, yet the logic is fantastical. This is not denial in its loudest form, nor is it outright refusal. It’s more complicated: Didion lets the irrational coexist with her voice, refusing to tidy it away with explanation.

“I knew he was dead. I also believed that if he was dead it was because I had failed to get him to the hospital in time.”

This sentence pairs fact with illusion in one breath. It captures the psychic contradiction of grief: knowledge and belief diverge, and guilt becomes a coping mechanism. Didion knows she is not responsible, but responsibility offers a kind of order. The syntax of the sentence folds in on itself: the cause is illogical, but the feeling is precise; knowledge becomes subordinate to belief. What matters is not what’s real, but what can be controlled.

For a broader analysis of Didion’s most resonant lines and their function across the memoir, see: 8 Striking Quotes from The Year of Magical Thinking.

Cultural and Historical Context

Grief in the Early 21st Century

When Magical Thinking was published in 2005, the literary world was not short of memoirs. What it lacked, however, were memoirs of grief that defied easy answers. The post-9/11 cultural moment was saturated with language of healing, closure, and resilience, terms that suggest narrative completeness. Didion offered none of that.

Her book landed in a public atmosphere increasingly uncomfortable with ambiguity. Popular nonfiction at the time often followed a predictable arc: trauma, crisis, recovery, redemption. Didion broke that model. She presented grief not as a singular event to be overcome, but as a state of suspended comprehension. Readers were not guided toward catharsis; they were asked to sit inside uncertainty.

This reluctance to narrative closure gave the book its cultural heft. It felt honest at a time when honesty was often filtered through the logic of self-help mechanisms. Didion’s refusal to recover became its own kind of ethical stance. She was not offering guidance to a chaotic world but was merely a company in the dark.

Private Loss, Public Echo

Didion was already a towering figure when this book appeared, but Magical Thinking fundamentally repositioned her. It established her not just as an essayist of national unrest or California disillusionment, but as the chronicler of a profound inner disintegration. The sharpness of her control, once trained on politics and ideology, turned inward. And readers followed.

The memoir’s influence reached a different stage when Vanessa Redgrave performed it as a one-woman play on Broadway in 2007. While critics praised the production, the book’s deeper significance was revealed in how it passed from hand to hand—less as a text to be studied than as a companion for the bereaved. It earned trust not by explaining loss, but by honoring its disorientation.

From a contemporary perspective, Magical Thinking signaled a turn in personal writing. It validated a literary memoir that dwells in finality without resolving it, that rejects tidy arcs, and that meets the reader without simplification. The book created a space for narratives that inhabit difficult states of mind rather than seeking release from them.

For a closer look at the reciprocal relationship between The Year of Magical Thinking and its cultural moment, see the full article: What Didion Doesn’t Say: The Historical Context Behind The Year of Magical Thinking.

Other Works on Loss, Memory, and Control

Didion’s account of grief is singular in its execution, but it does not stand alone. Her book belongs to a lineage of literary texts that examine death not as an endpoint, but as a problem of thought, language, and memory. For readers who found themselves altered by Didion’s memoir, the following works offer kinship, tension, or deepened inquiry.

- C. S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed (1961) is perhaps the closest spiritual companion, if not in tone, but in structure. Like Didion, Lewis avoids narrative smoothness. He stumbles, contradicts himself, and repeats. But where Didion’s voice remains pared and observational, Lewis’s is more explicitly wounded and anguished. The two writers circle similar voids, though their vocabularies, rational and spiritual, diverge.

- Megan O’Rourke’s The Long Goodbye (2011) enters the territory of modern elegy. More lyrical than Didion, O’Rourke interweaves personal memory with cultural rituals of mourning, often challenging the limited language available for loss. Where Didion documents the architecture of grief, O’Rourke explores the atmospheric weather of it.

- Max Porter’s hybrid novel Grief Is the Thing with Feathers (2015) breaks all formal boundaries. His book is surreal, compressed, nonlinear. A giant crow serves as an avatar for grief: aggressive, absurd, tender, and mocking. For readers drawn to Didion’s structural daring, Porter offers a radically different, yet equally profound, approach to articulating sorrow.

- Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Notes on Grief (2021), a more recent entry, takes Didion’s cool control and pulls it through a global and familial lens. It is brief, sharp, and devastating. Adichie does not try to make sense of her loss. Instead, she tolerates its gravity to dissolve all structure. The restraint remains, but the rawness lies closer to the surface.

These works do not just echo Didion’s book; rather, they converse with it. Each book treats grief not as a theme, but as a condition that alters the function of language. And like Didion, they refuse to resolve, leaving spaces open and undiagnosed for the reader to sit inside them with uncertainty.

Going back to Magical Thinking after encountering these books can deepen one’s sense of its precision. Didion’s voice never wavers, yet the restraint she builds is architectural and full of intention. With that control, the full dimension of loss comes into view. Within it, we recognize something we’ve known all along, even if we’ve never said it aloud.

For more on how these and other contemporary works echo, counter, or extend Didion’s literary style, visit: Books Like The Year of Magical Thinking: Grief Memoirs That Go Deeper.

Why This Book Still Holds

The Year of Magical Thinking endures as essential reading not by instructing us on grief, but by declining to do so. It provides no lessons, no finality, and no emotional peace. The book reveals grief’s internal logic: its circular time, its splintered memory, and its defiance of narrative order. Didion builds a precise, fragile structure that echoes the inner turmoil of loss, offering neither explanation nor solace.

If this article has provided insight into Didion’s thought process, language, and cultural perspective, there is still more to explore. Each part of this analysis connects to a more in-depth look at her style, her use of repetition, the time period she lived in, and the broader literary effects of her grief. These supporting pieces extend and enrich the discussion, offering a fuller picture of a book that deepens and rewards the more you examine it.

Further Reading

Q: How were you able to keep writing after the death of your husband? A: There was nothing else to do. I had to write my way out of it by Emma Brockes, The Guardian

2005 interview: Joan Didion on her ‘Year of Magical Thinking’ by Kritin Tillotson, Star Tribune

My sister gave me a copy of Joan Didion’s ‘The Year of Magical Thinking,’ and the late author’s memoir greatly changed my perspective by Mara Leighton, Business Insider

25 Years Ago, Joan Didion Kept a Diary. It’s About to Become Public. on Reddit