Explore This Topic

- The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion: A Deep Literary Analysis

- Why Joan Didion’s Prose Style Works in The Year of Magical Thinking

- Grief, Memory, and Magical Thinking: Themes in Didion’s Work

- 8 Striking Quotes from The Year of Magical Thinking (And What They Reveal)

- Books Like The Year of Magical Thinking: Grief Memoirs That Go Deeper

- What Didion Doesn’t Say: The Historical Context Behind The Year of Magical Thinking

Joan Didion’s memoir The Year of Magical Thinking (2005) chronicles the year following the sudden death of her husband, John Gregory Dunne, in late 2003, a year that also saw their daughter Quintana in a life-threatening coma. It is a sobering, clear-eyed account of grief and an attempt to make sense of the unimaginable.

Didion’s characteristically precise prose becomes a vehicle for exploring the disorientation of bereavement: the shock and denial, the looping memories, the warping of time, the inadequacy of language, and the reconstruction of one’s identity after loss. Throughout the memoir, certain lines that encapsulate Didion’s thematic concerns and stylistic approach ring out with striking insight.

Below, we examine eight such quotes selected according to the book’s common themes like grief, memory, denial, language, and identity. We then explore what each reveals about Didion’s journey through mourning. In each case, we consider the context of the quote in the memoir, the insight it offers about Didion’s experience, and the literary or critical resonance surrounding it.

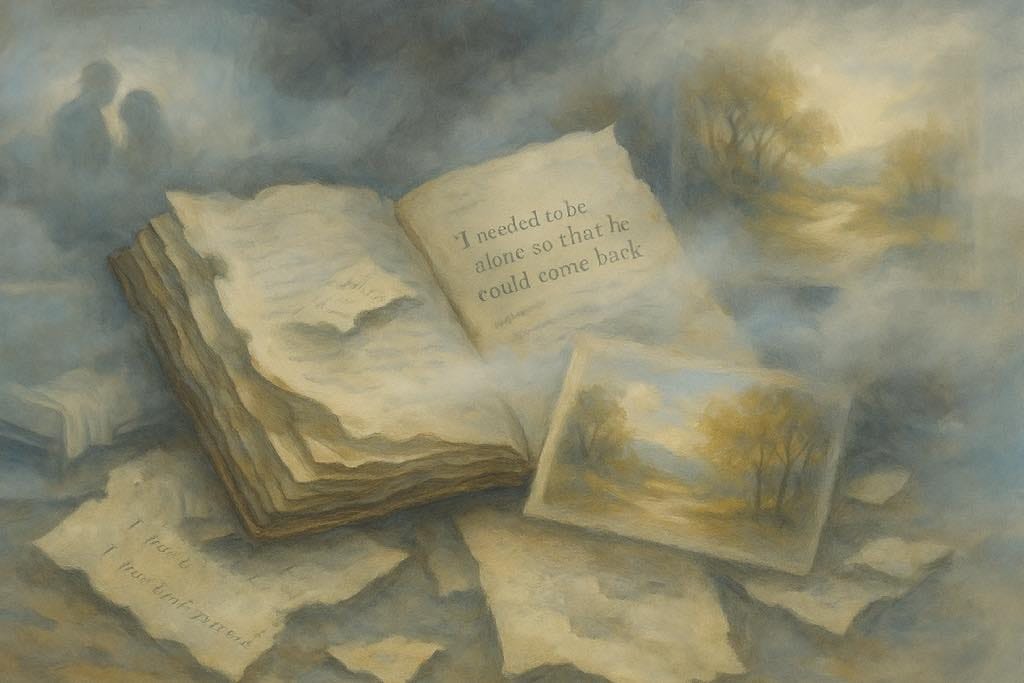

1.

“I needed that first night to be alone so that he could come back. This was the beginning of my year of magical thinking.”

p. 33

In the immediate aftermath of John’s death, Didion finds herself gripped by an irrational but overpowering idea: if she stays alone on that first night, perhaps her husband will somehow return. This quote appears early in the memoir, as Didion recounts the hours after leaving the hospital without John.

The simple, matter-of-fact tone belies the absurdity of the thought—she knows on a rational level that John is dead, yet she behaves as if his return were possible. Didion herself labels this “the beginning of my year of magical thinking,” directly acknowledging that she has entered a state of mind where normal logic does not apply.

The context here is Didion’s description of how she avoided calls and company that night; part of her believed that if no one else was around, the impossible might happen. This is grief’s denial in its purest form, an involuntary, almost childlike bargaining with reality.

Thematically, this quote lays bare Didion’s central struggle with accepting finality. It reveals the “magical thinking” of the title: a form of denial and hope that defies logical sense. In classical models of grief (such as Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s stages), Didion’s mindset corresponds to the denial or bargaining phase, when the bereaved cannot fully process the permanence of loss.

However, Didion’s portrayal of denial is uniquely intimate and unadorned. She does not dramatize it with hysteria; she presents it in cool, clinical prose (I needed to do X so that Y might happen). Here, one short sentence (“This was the beginning of my year of magical thinking”) serves almost as a diagnosis of her own condition.

The quote reveals how her mind, desperate for John, concocted a rule (be alone = he’ll come back) that she intellectually knows is false. In doing this, she lets us witness the poignant disharmony between intellect and emotion that defines the grieving process. It’s a gentle reminder that profound grief often involves, as Didion says elsewhere, being “literally crazy” in ways one would never predict.

2.

“We are not idealized wild things. We are imperfect mortal beings, aware of that mortality even as we push it away, failed by our very complication, so wired that when we mourn our losses we also mourn, for better or for worse, ourselves. As we were. As we are no longer. As we will one day not be at all.”

p. 198

This remarkably reflective quote appears toward the end of the book as Didion considers the universal aspects of grief and mortality. In a sweeping, lyrical statement, she suggests that mourning the death of a loved one is also an act of grieving for one’s own past, present, and future selves.

The context in the memoir is a moment of philosophical insight: Didion is stepping back from her personal story to generalize about the human condition. She rejects any romantic notion that we are “idealized wild things” immune to pain, instead emphasizing that we are frail, “imperfect mortal beings.”

The triple reprise that follows —”As we were. As we are no longer. As we will one day not be at all.”—strikes a rhythmic, almost liturgical tone, as if echoing a prayer. These short-fragment sentences hammer home the stages of the self that are implicated in grief: the person we used to be (when our loved one was alive), the person we have ceased to be with their loss, and the person we will ultimately become (or cease to be) in our own mortality.

Thematically, this quote reveals Didion’s profound understanding that grief is intertwined with identity. When someone close to us dies, it isn’t only their absence we mourn, but also the loss of the life we lived with them. Didion articulates this by saying, “When we mourn our losses we also mourn… ourselves.” This speaks to the way John’s death forced her to mourn the Joan she was when John was alive—a Joan who, in some sense, no longer exists. In grieving him, she is inevitably grieving the end of that version of Joan.

The quote’s resonance extends further: it implicitly references the idea that all mourning contains an element of self-mourning because it confronts us with our own mortality. The phrase “aware of that mortality even as we push it away” suggests that people carry knowledge of death’s inevitability but usually suppress it, until a bereavement forces it to the surface.

3.

“I could not count the times during the average day when something would come up that I needed to tell him. This impulse did not end with his death. What ended was the possibility of response.”

p. 194

Here, Didion poignantly captures the everyday reality of loss: the persistent impulse to share life’s moments with someone who is no longer there. This quote comes from later in the memoir, as Didion reflects on the countless times she finds herself reaching mentally toward John to remark on a story, ask a question, or simply hear his opinion, only to remember he is gone.

The context is the accumulation of mundane experiences that suddenly turn tragicomic: reading an article, noticing something odd in the news, experiencing a small victory or frustration—all those little sharable pieces of a day that now have nowhere to go. Didion confesses that the impulse to tell John these things is undiminished; what’s changed, brutally, is that there will never be an answer.

“What ended was the possibility of response.” The finality of that line lands like a quiet blow. Her phrasing is characteristically precise; she doesn’t say conversation ended, only the possibility of response. That single word “possibility” emphasizes the absolute nature of death’s separation. It underscores that even though she can still talk to John in her mind, she must face the silence that follows.

Stylistically, the quote is straightforward and unadorned, which heightens its emotional impact. The brevity and parallel structure of these lines lend them an undeniable truth, hammered in by experience. There is also a subtle rhythm: “did not end” vs. “ended was.” The inversion in the next sentence (putting “What ended” at the start) draws attention to the final word “response.” It hangs there, emphasizing the silence that has descended on her life.

The quote underlines that absence is not a one-time realization but a series of discoveries: each unshared observation is a new encounter with John’s death. In exploring this, Didion also implicitly touches on how grief intersects with memory (each impulse to speak is sparked by memory or habit) and with language (she still has words to say, but no recipient). The loss of a loved one is shown to be the loss of an audience and counterpart for one’s life.

4.

“Given that grief remained the most general of afflictions its literature seemed remarkably spare.”

p. 44

Early in her mourning, Didion (ever the researcher and writer) turns to literature and cultural guides to understand what she is experiencing. This quote captures her surprise (and mild scorn) at discovering that there is relatively little written wisdom on grief, despite the universality of the experience.

It appears around page 44 of the memoir, where Didion catalogs the few sources she found: C. S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed (1961), some lines in novels like Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain (Der Zauberberg, 1924), and not much else. The tone carries a hint of Didion’s trademark dry skepticism. She calls grief “the most general of afflictions,” meaning nearly everyone will endure it at some point, yet notes the irony that its literature is “remarkably spare.”

Didion implicitly asks: if grief is so common, why do we collectively have so little to say about it? The answer might be that grief had long been treated as a private, even taboo subject, one reason Didion’s memoir was so groundbreaking. By pointing out the sparsity of grief literature, she positions Magical Thinking as an attempt to fill that gap, or at least to add her voice to a small chorus.

Additionally, this quote touches on the theme of language and its limits. Grief, she finds, defies easy articulation; perhaps that’s why its literature is spare. In a later reflection, she even laments needing more than words to convey what she feels (wishing for a film editor’s tools to compress time and show all frames of memory). So here, early on, Didion is grappling with the inadequacy of existing narratives.

Indeed, this moment in the memoir shows Didion adopting a research attitude: she temporarily becomes an investigator of grief rather than simply a sufferer of it. This distancing can be seen as a form of control (more on that in the next section). The sentence’s cool, almost clinical tone is part of that. It’s as if Didion momentarily puts on her reporter hat: surveying the literature and reporting the surprising finding that even in the library, grief leaves one “alone.”

From a critical perspective, Didion’s observation here has been echoed by others and even rectified in recent years by an explosion of grief memoirs. But in 2005, when her book was published, there were indeed relatively few first-person accounts of grief in popular literature. (Lewis’s A Grief Observed from 1961 was a standout; another was H/Harriet Vehse’s Widow in 1979, but such works were not widely known.) Didion’s noting of this sparseness might also hint at a subtle critique: perhaps we avoid writing or reading about grief because it’s uncomfortable, or perhaps those who grieve often lack the capacity to write about it until much later (if at all).

5.

“In time of trouble, I had been trained since childhood, read, learn, work it up, go to the literature. Information was control.”

p. 44

This quote immediately precedes Didion’s remark on the sparse literature of grief. She acknowledges that her instinct, ingrained from an early age, is to respond to any crisis by gathering information. The cadence of the first sentence (“read, learn, work it up, go to the literature”) sounds almost like a set of instructions or a mantra she was taught. It reflects her upbringing and her career: she’s someone who believes in the power of research and intellect to tackle problems.

The definitive statement that follows, “Information was control,” distills her creed: if you can just find the right facts, the right analysis, you can master the situation. In the context of the memoir, Didion lives this methodology. After John’s death, she obsessively studies his medical records and autopsy report. She notes details like the exact time the ambulance took to arrive, the specific ventricular fibrillation that killed him, the percentages and odds from clinical studies. It’s as if by mastering the technical details of how and why things happened, she might somehow undo or at least comprehend the what.

It’s a form of magical thinking in itself: the belief that mastering the information might grant some agency or at least shield her from further shock. In fact, Didion hints that part of her magical thinking manifested as a conviction that if she could understand John’s cardiac event fully, perhaps there was a way to reverse it or a detail that would change the outcome. She even insisted on an autopsy, partly in the hope that doctors could “find out what was wrong so they can fix it,” a poignant example of how her need for facts overlapped with an unconscious denial of finality.

The idea that “information was control” also speaks to Didion’s identity as a writer and journalist. Writing nonfiction, she had long relied on research to bring order to chaos. Now, faced with a personal tragedy, she reverts to that training. But grief stubbornly repels such order, a point Didion gradually realizes. No amount of medical detail can truly explain why John is gone or bring him back.

The subtext becomes clear: if information truly equaled control, then why does she still feel so unmoored? Over the course of the book, the limits of this mantra become apparent. Didion cannot control life or death with knowledge. Rationality has only limited power over the irrational surges of hope and denial. Thus, the quote is somewhat tinged with irony by the memoir’s end.

6.

“No. The way you got sideswiped was by going back.”

p. 53

As the shock of loss evolves, Didion discovers that simply remembering can ambush her with pain. This quote comes from a passage where she describes what she calls the “vortex effect”: the sudden, uncontrollable waves of memory and emotion that knock her off course.

In context, Didion is admonishing herself. The line begins with a firm “No,” as if refuting an internal voice that tempted her to mentally “go back” in time. “The way you got sideswiped was by going back,” she notes, using a vivid metaphor of being broadsided by an oncoming car. By addressing herself as “you,” Didion universalizes the warning: it’s a second-person injunction that could apply to anyone grieving.

Didion finds that innocuous stimuli can set off cascades of recollection; for instance, seeing spring blossoms along Highway 101 unexpectedly spirals into thoughts of her life with John. In the memoir, she writes that even seemingly “innocuous” memories could hit her “as though she were sideswiped.” The “vortex” motif signifies how grief flouts any attempt at linear healing; one moment she might be functioning normally, the next she is sucked into an inward spiral of remembrance.

It’s worth noting the resonance of this idea with Didion’s earlier famous line (not one of our focal eight, but foundational in her narrative):

“Grief comes in waves, paroxysms, sudden apprehensions that weaken the knees and blind the eyes and obliterate the dailiness of life.”

p. 27

The “sideswipe” is essentially one of those waves, a sudden blow of memory that momentarily blinds her to her current surroundings. Didion internalizes the incident as a lesson: the only way to avoid being ambushed is to avoid “going back” in one’s mind; essentially, to avoid dwelling on the past. Of course, such avoidance is neither fully possible nor truly healthy long-term, which Didion likely knows.

But in the throes of early grief, this quote shows her instinct for self-preservation: she attempts to control her grief by controlling her thoughts, sticking to what she calls the “correct track” of the present. Ironically, as the memoir progresses, Didion cannot always steer clear of the vortex; the memories will return despite her efforts.

7.

“As a writer, even as a child, long before what I wrote began to be published, I developed a sense that meaning itself was resident in the rhythms of words and sentences and paragraphs… The way I write is who I am, or have become…”

p. 7

At the beginning of the memoir, Didion turns a reflective gaze on language and her own writing process, acknowledging how integral writing is to her identity and how it drives her effort to understand John’s death. This quote is part of a longer passage in which she confesses that, despite a lifetime of finding solace and sense through writing, in the case of profound grief, even her trusted tools seem to falter.

She admits that she wishes she had the equivalent of a film editor’s cutting room to convey the full reality of her memory and emotions. Nonetheless, she asserts something crucial: “The way I write is who I am, or have become.” Writing is not just her profession; it’s her core identity and coping mechanism.

Didion is grappling with the limits of narrative to capture the truth of what she’s been through. By saying “meaning itself was resident in the rhythms of words,” she recognizes that it’s not only the semantic content of language that conveys truth, but the style, the cadence, the very form of expression. This is a key to understanding Didion’s prose in the entire memoir: the repetitions, the fragmentary sentences, the looping structure all mirror her mental state and help evoke sense beyond factual recounting.

Even in this self-analytical quote, Didion’s distinctive rhythm is on display. She uses a long, winding sentence to describe her lifelong relationship with writing, then delivers the conclusion: “The way I write is who I am” is almost like a revelation or a creed. The rhythm of her sentences provides a sense of stability when her inner world is reeling. Notably, the phrase “the rhythms of words and sentences and paragraphs” itself has a rhythm: the repetition of “and” and the progression from words to sentences to paragraphs draw the reader into the cadence she’s describing.

Some literary analysts note that Didion’s use of repetition and circular structure in the memoir mimics the thought patterns of trauma survivors (returning again and again to the moment of shock). What Didion adds is a self-reflexive awareness: she knows she is doing this and even why. By including this quote, she essentially pulls back the curtain for the reader, saying: This is why I’ve written this book the way I have. “The way I write is who I am” thus becomes a key to reading the memoir: to understand her in grief, we must pay attention not only to what she says but also to how she says it.

8.

“Marriage is memory, marriage is time… Marriage is not only time: it is also, paradoxically, the denial of time.”

p. 197

Didion offers this insight as she contemplates what her forty-year marriage to John meant and how his absence has altered her perception of herself. The quote occurs in a section where she reflects on how she had viewed her life and identity through the prism of her marriage. “Marriage is memory, marriage is time,” she writes; it is a declaration that a long marriage is fundamentally built on shared history.

Every marriage accumulates a trove of joint memories; it is a narrative that two people build together over time. But then she adds a twist: “Marriage is not only time: it is also, paradoxically, the denial of time.” This paradox speaks volumes about Didion’s experience. In context, she elaborates that for 40 years she saw herself through John’s eyes, and in that reflection she “did not age.” Only after John’s death did she realize that, “for the first time since I was 29, I saw myself through the eyes of others… I realized that my image of myself was of someone significantly younger.” In other words, being married had, in a sense, frozen time for her, or at least shielded her from the usual sense of aging, because within the marriage, they sustained an image of each other that was timeless.

Didion’s phrase “denial of time” suggests that within their partnership, they had a stable sense of each other that didn’t acknowledge decay or change—he would always be the man who knew her from her youth, and she would always be that younger Joan in his eyes. This is an immensely poignant idea: that one function of a long marriage is to provide a sort of safe zone where the brutal passage of time (aging, mortality) is kept at bay, at least in the couple’s own minds.

This quote underscores why John’s death is not just the loss of a companion but the end of that temporal bubble. Suddenly, time catches up. Didion explicitly notes that only after John was gone did she confront how others saw her: as an elderly widow, not the ageless Joan of John’s view. Thus, this quote is about denial in a different sense, not the denial of death per se, but the denial of aging and change that a marriage can unconsciously cultivate.

Didion’s prose often achieves profundity through just such economy and balance. The clarity of these lines belies the layers of emotion beneath. In terms of technique, it also resonates with Didion’s penchant for recursive thought: she states something, then circles back to complicate it. The paradox of time here also mirrors the book’s broader structure, where Didion frequently loops back in time, retelling events and memories, almost as if to wrestle against the forward march of time without John.

Further Reading

The Year of Magical Thinking Quotes on Goodreads