Explore This Topic

- The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion: A Deep Literary Analysis

- Why Joan Didion’s Prose Style Works in The Year of Magical Thinking

- Grief, Memory, and Magical Thinking: Themes in Didion’s Work

- 8 Striking Quotes from The Year of Magical Thinking (And What They Reveal)

- Books Like The Year of Magical Thinking: Grief Memoirs That Go Deeper

- What Didion Doesn’t Say: The Historical Context Behind The Year of Magical Thinking

Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking (2005) is a spare, intensely personal memoir of grief, written in the aftermath of her husband’s sudden death and during their daughter’s grave illness. On the surface, it reads as an inward-looking account of one woman’s emotional journey. Yet the book is suffused with unspoken context on historical currents and cultural underpinnings that Didion herself does not spell out, but which deepen the memoir’s resonance.

From the national mood of the early 2000s to evolving social attitudes about mourning, understanding the book’s implicit contexts can enrich our appreciation of Didion’s work. This article explores what Didion doesn’t say in her memoir: the broader historical and cultural forces that informed the book and its reception.

The Cultural Climate of Post-9/11 America

Didion’s memoir emerged at a time when America was reeling from the shock of the September 11, 2001 attacks and their aftermath. The early 2000s were a period of collective mourning and anxious introspection. Public discourse was preoccupied with sudden loss, trauma, and the fragility of life, themes that uncannily parallel Didion’s personal story.

Although the book does not explicitly mention 9/11, it was published only four years after the attacks, into a society that had been forced to confront mortality on an unprecedented scale. This post-9/11 cultural climate forms a crucial backdrop to Didion’s narrative. Readers in 2005, steeped in the imagery of memorials and the language of grief, would have intuitively connected Didion’s private bereavement with the atmosphere of a national tragedy.

Didion herself was an acute observer of American responses to tragedy. In a 2003 lecture (later published as “Fixed Ideas: America Since 9.11”), she critiqued the nation’s reaction to the September 11 attacks, noting how even a calamity of that magnitude was swiftly swathed in sentiment and political symbolism. She pointed out, for example, that some officials had been quick to find “upside aspects” in the surge of patriotic feeling after 9/11, a wave of public emotion that could be exploited and packaged for various agendas.

This impulse to domesticate grief into comforting clichés is something Didion implicitly avoids in her own memoir. Magical Thinking takes its very title from an acknowledgment of irrationality, the “magical” thought patterns by which she, and by extension any mourner, tries to cope with the unimaginable.

Writing in a post-9/11 world, Didion could assume readers knew the feeling of waking up to a reality that had irreversibly changed in an instant. Even without referring to global events, Didion’s chronicle of personal catastrophe spoke to a society that had recently experienced a very public one. Her calm, precise voice stood out against the bombast of patriotic memorializing, offering a different kind of testament to sudden loss.

Thus, the post-9/11 milieu gave Magical Thinking an added layer of relevance: it was a private grief memoir that doubled as a subtle counternarrative to the sentimental handling of collective grief in the culture at large.

Evolving Medical and Social Attitudes to Death and Grief

One of the threads subtly traced in Didion’s memoir is the changing way modern society deals with death, especially the medicalization of dying and mourning in the late 20th century. Didion does not explicitly lecture on this history, but through her story she hints at the stark contrast between an earlier era’s intimate, ritualized engagement with death and today’s more clinical, institutional approach.

Over the course of the twentieth century, death in America gradually moved out of the home and into the hospital. In generations past, a family member’s final moments and mourning period unfolded within the home and community, governed by familiar rituals. By the 2000s, however, most deaths occurred under medical supervision, and the care of the dying, as well as the handling of the body and the comforting of survivors, had become the province of professionals.

Didion’s experience reflects this shift. Her husband, John Gregory Dunne, suffers a massive cardiac arrest at home, but within minutes an ambulance arrives and rushes him to a Manhattan hospital where, in a fluorescent-lit emergency room, he is pronounced dead. Her daughter Quintana, stricken by septic shock, is kept alive for days in an intensive care unit, attached to monitors and tended by teams of specialists. The memoir captures how quickly a private tragedy is subsumed into the protocols of the modern hospital.

As medical advances in the 20th century conquered many once-fatal illnesses and prolonged life, death became less visible in daily life, and when it did occur, it often felt like an aberration or even a failure. In earlier times, the bereaved were expected to lament their loss loudly through prescribed rites; in our time, prolonged or overt mourning is often treated as a pathology to be hurried along.

Throughout the book, Didion grapples with the chasm between her intimate sorrow and the institutional frameworks that surround it. She recounts, for example, the jarring moment when a hospital representative called mere hours after her husband’s death to inquire about organ donations. The request was medically routine and a matter of protocols and transplant lists, yet to Didion it felt surreal, even ghoulish, coming so soon in her raw grief.

Similarly, while her daughter lay in a coma, Didion turned to medical literature (intensive care journals, neurology manuals) in an effort to understand the terminology and regain a semblance of control. This instinct to respond to death through research reflects not only Didion’s disposition but also the broader modern trend of entrusting life and death to expert knowledge. In an era of high-tech medicine, families often find themselves, like Didion, becoming students of diagnoses and prognoses, a far cry from the home-based, ritual knowledge of death that sufficed in earlier generations.

A Changing Literary Landscape of Memoir

Beyond its personal and historical content, Magical Thinking also belongs to a specific literary moment. The early 21st century saw an explosion of memoirs in American publishing. The so-called “memoir boom” of the 1990s and 2000s put countless personal narratives on bookstore shelves, reflecting an enormous hunger among readers for true stories of individual experiences.

By 2005, memoir was one of the dominant literary forms, and readers had become accustomed to first-person accounts of trauma, loss, and survival. In this context, Didion ventured into the territory of intimate memoir and found a ready audience. Yet her approach to life writing stood apart from many contemporaries. Whereas some popular memoirs of that era veered into melodrama or sensationalism, Didion’s book remained restrained, precise, and probing.

Didion’s entry into memoir was also notable because of her literary pedigree. By 2005 she was a revered figure in American letters, an essayist-novelist known for her cool, incisive prose and her role in the New Journalism movement of the 1960s and 70s. The publishing world treated Magical Thinking not just as another grief memoir, but as an event: a major writer turning her gaze inward. This mirrored a broader shift in publishing; other acclaimed authors of Didion’s generation were also embracing memoir later in their careers. Not long after Didion, novelists like Joyce Carol Oates and Joan Wickersham would publish their own reflections on loss.

The commercial and critical success of Didion’s book reinforced the idea that memoir could be high art. Her book’s rigor not only lent the work intellectual heft; it also implicitly commented on the memoir genre itself, suggesting it could do more than simply elicit empathy or tears: it could illuminate the human condition in a broader sense. Didion’s contribution was to show that a memoir of grief need not follow the expected script of overcoming and closure.

Didion’s World: Generational and Personal Influences

To fully understand what the book does and does not say, one must consider Didion’s own background. She was born in 1934, came of age in the post-World War II era, and entered writing during the transformative 1960s. Her generational identity and life experiences are subtly woven into the fabric of the memoir. Though she rarely references herself outside the immediate scope of husband, daughter, and hospitals, the way she processes grief cannot be separated from who she is and the times that formed her.

Didion belongs to the generation that bridged the old world and the new. As a young woman, Didion moved from her provincial California upbringing to the bustle of New York’s literary scene. Along with contemporaries like Norman Mailer and Tom Wolfe, Didion became a leading voice of New Journalism—a style blending subjective perspective with fact.

Didion and Dunne in their early married years exemplified a kind of bohemian intellectual life: they were writers without strict rules, a couple who could pin daisies in their hair or dress their toddler in whimsical outfits and consider it part of life’s grand improvisation. At the same time, they shared a posture of critical detachment that came to define much of the political and cultural discourse of the sixties: skeptical of institutions, wary of consensus, and allergic to official narratives.

Didion’s personal milieu also includes the rarefied literary and Hollywood circles in which she and Dunne moved. For decades, the couple lived between California and New York, writing screenplays and articles, and hosting dinner parties with actors, directors, editors, and intellectuals. By the time of John’s death in 2003, the two had been each other’s closest collaborators and confidants for nearly forty years—a partnership of remarkable intimacy (as the memoir itself documents).

Reception and Cultural Impact

When Magical Thinking was published in late 2005, it was met with widespread acclaim and became an unexpected commercial success. The reception of the book is itself part of its historical context, revealing how Didion’s personal story struck a chord in the culture of the time. Far from a niche project, the memoir quickly climbed bestseller lists. There was, indeed, an outpouring of sympathy and admiration for Didion not only as a literary figure but as a woman who had survived the unthinkable and transformed it into art.

The book’s critical positioning was distinctive. It wasn’t merely reviewed as a moving memoir; it was discussed as an important cultural text about how we deal with death. In high-profile forums, writers grappled with Didion’s implications. Some noted how her insistence on truth-telling in grief served as a counterpoint to self-help culture. The memoir won the 2005 National Book Award for Nonfiction and was also a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award. Decades later, its stature would only grow: in 2024, The New York Times Book Review ranked it as 12th of the 100 best books of the twenty-first century up to that point.

Perhaps one measure of the memoir’s cultural impact was its adaptation to another medium. In 2007, Didion adapted the book into a one-woman Broadway play, directed by David Hare and starring Vanessa Redgrave. The stage production distilled the memoir’s essence into an evening of theater, and audiences heard Didion’s words spoken aloud. This theatrical afterlife of the memoir indicates how fully Didion’s story had entered the public conversation: her personal tragedy had become a shared cultural narrative that people wanted to see interpreted on stage.

The reception and discourse around Magical Thinking confirmed that what Didion doesn’t explicitly explain in the book was nevertheless felt and appreciated by readers. Critics and readers saw the book as timely and timeless: a chronicle of one winter in a woman’s life that also serves as an X-ray of the modern soul in grief. By illuminating her personal darkness with such clarity, Didion had provided a kind of gentle guidance for a culture that often finds itself at a loss for how to deal with death.

###

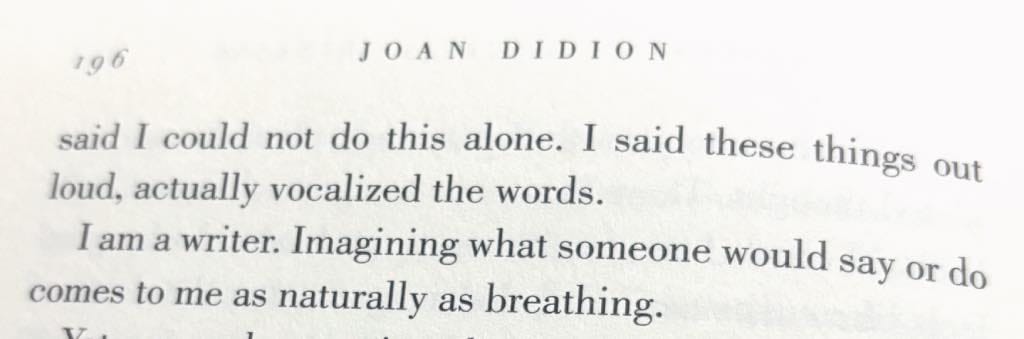

“I am a writer. Imagining what someone would say or do comes to me as naturally as breathing.”

Page 196, The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion

Further Reading

In Grief, Joan Didion’s Move From Fiction to Memoir by David Ulin, Literary Hub