Explore This Topic

- The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion: A Deep Literary Analysis

- Why Joan Didion’s Prose Style Works in The Year of Magical Thinking

- Grief, Memory, and Magical Thinking: Themes in Didion’s Work

- 8 Striking Quotes from The Year of Magical Thinking (And What They Reveal)

- Books Like The Year of Magical Thinking: Grief Memoirs That Go Deeper

- What Didion Doesn’t Say: The Historical Context Behind The Year of Magical Thinking

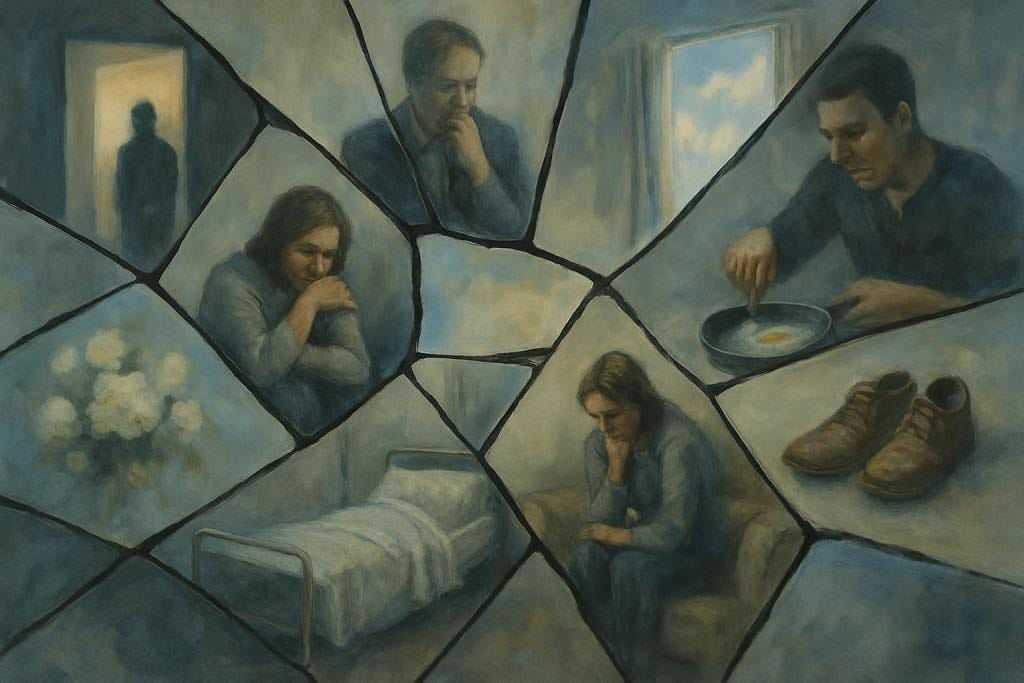

Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking (2005) is often hailed as a classic of mourning literature—a raw yet exquisitely controlled memoir of the year following the sudden death of her husband, writer John Gregory Dunne. In that “ordinary instant” when Dunne collapsed of a heart attack at their dinner table, Didion’s life was irrevocably divided into a “before” and “after.” The book that emerged from the aftermath is not just a chronicle of personal loss but an exploration of grief’s disorienting terrain, the workings of memory, and the peculiar logic of “magical thinking” that overtook her in mourning.

This article examines those central themes, e.g., grief, memory, and magical thinking, as they develop across Didion’s memoir, focusing on the ways her narrative structure and voice give expression to them. We also consider Magical Thinking in light of literary and psychological theories of mourning, trauma, and memory to uncover how Didion’s experience both echoes and challenges these frameworks.

Grief as Disorientation and “Insanity”

Didion’s memoir insists that grief is qualitatively different from what even the most imaginative among us expect. “Grief turns out to be a place none of us know until we reach it,” she observes, emphasizing the futility of imagining how one might respond to loss. Before John’s death, Didion, like most people, assumed grief would be an intensification of normal emotions—sadness, primarily. What arrived instead was far stranger and more destabilizing: a full-body dislocation from normal logic, memory, and even physical reality.

Cognitive Disarray and the Limits of Rationality

One of Didion’s core realizations is that intense bereavement can resemble a temporary mental illness. In her words:

“We might expect that we will be prostrate, inconsolable, crazy with loss. We do not expect to be literally crazy, cool customers who believe their husband is about to return and need his shoes.”

Here, Didion admits that in her grief she exhibited delusional and irrational thinking she never anticipated, a theme to which we will return in detail as magical thinking. She documents how grief altered her cognitive functioning: she experienced confusion, impaired memory and concentration, and an underlying sense of derangement. Didion even turned to clinical literature and accounts by psychologists for context, finding surprisingly little in this feeling of outright insanity accompanying loss.

In framing grief as a kind of transient madness, Didion aligns with what some theorists of mourning have noted anecdotally but which popular culture often glosses over. Her memoir thus expands our understanding of mourning beyond sadness into the realm of cognitive and perceptual disturbance, a world where normal logic loosens and one’s sense of reality is fundamentally shaken.

Public Composure vs. Inner Collapse

Crucially, Didion’s portrayal of grief also engages with the cultural expectations and stigmas surrounding bereavement. From the start, she is aware of the unwritten social script that demands the bereaved remain composed and “not indulge” in overt displays of despair. On the night of her husband’s death, she recalls writing a note to herself: “the question of self-pity,” as if reminding herself to avoid that taboo at all costs.

American culture, like that of other Western societies, often treats extended or visible grief as socially disruptive. Didion draws on Geoffrey Gorer’s 1965 study Death, Grief, and Mourning, which observed a rising pressure in both the U.S. and England to suppress mourning in public. Gorer argued that grief had come to be seen less as a natural response and more as a form of self-indulgence. Those who managed to hide their sorrow were admired for their restraint, embodying a new social imperative to keep grief subdued.

In the memoir, she dutifully plays the part of the “cool customer,” appearing calm and organized in the immediate aftermath (making funeral arrangements, interacting with doctors) even as internally she feels she has “crossed one of those legendary rivers that divide the living from the dead,” visible only to others who have recently suffered loss.

This split between outward composure and inner chaos is a running theme. Didion exposes it to critique the cultural pressure to “get over” loss quickly. “We have been conditioned to treat mourning as self-indulgence,” she notes, and to prize the bereaved who soldier on as if nothing has happened. By detailing her own experience of concealing profound disorientation beneath a functional exterior, Didion’s book implicitly calls out these unrealistic expectations and exposes the true nature of grief.

Challenging the Pathologization of Grief

Notably, Didion’s account resonates with and yet challenges classic grief theories. Sigmund Freud’s seminal essay “Mourning and Melancholia” (1917) drew a line between “normal” grief, which should resolve in due time as the survivor gradually withdraws emotional energy from the lost loved one, and pathological grief (melancholia), in which this detachment fails to occur.

Didion’s year of mourning challenges these boundaries. In many ways, her grief was adaptive—she survived, continued caring for her critically ill daughter Quintana, and ultimately did begin to comprehend John’s death—yet she also shows features Freud might label “melancholic,” such as an inability to let go of the deceased (keeping his belongings, irrationally expecting his return) for far longer than rationality would dictate.

Modern grief research has critiqued Freud’s insistence on “letting go” as the goal of mourning. In fact, contemporary bereavement experts like John Bowlby and Colin Murray Parkes have described a phase of “searching” and yearning that is common after loss, where the bereaved may literally or mentally search for the lost person (checking familiar places, seeing their face in crowds, or, as Didion did, feeling momentarily that the loved one will reappear).

The Looping Trajectory of Mourning

Far from pathological, such behavior is now understood as a normal part of acute grief. Didion’s experience exemplifies this searching phase vividly. Likewise, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s famous five stages of grief (originally formulated for the terminally ill but often applied to mourners—denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance) can be mapped only loosely onto Didion’s journey.

There is certainly denial in Didion’s story and a kind of bargaining (her mind’s superstitious attempts to undo reality), and eventually a measure of acceptance, but the process was not a linear march through discrete stages. Didion presents it as a fluid, looping trajectory—one step forward, one back—defying any neat model of “healing.”

In fact, she explicitly cautions against imposing facile narratives of recovery on the bereaved: “In the version of grief we imagine, the model will be ‘healing.’ A certain forward movement will prevail. The worst days will be the earliest…” she writes, only to demonstrate that in reality, grief has no predictable progression and the worst moments can ambush you long after the world assumes you are “over it.”

Grieving the Self, Not Just the Other

By the end of that first year without John, Didion does not claim to be “finished” with grief, but she has gained hard-won insight into its nature. She describes grief as a permanent alteration of one’s reality: “We are imperfect mortal beings… so wired that when we mourn our losses we also mourn, for better or worse, ourselves—as we were, as we are no longer, as we will one day not be at all.”

In mourning her husband, she was also mourning the end of the life they had together and the end of the person she was in that life. This blending of grief for the other and grief for one’s own changed identity underscores how profoundly loss can unnerve one’s sense of self. Yet Didion also comes to recognize a pivotal truth necessary for survival:

“If we are to live ourselves, there comes a point at which we must relinquish the dead, let them go, keep them dead.”

This stark acknowledgement (that she had to finally accept John was gone and could not be bargained back) marks the beginning of Didion’s reluctant acceptance. This acceptance is not closure, a term she despises for its falsity, but rather a recognition of reality. In a sense, her memoir charts a movement from near-unreason and shock toward a clearer-eyed reckoning with mortality. That arc, however uneven, is what gives Magical Thinking its narrative form and its cathartic power.

Memory, Time, and the “Vortex”: The Persistence of the Past

If grief upended Didion’s sense of reason, it also profoundly altered her relationship with memory and time. Throughout the book, the past continually floods the present, often without warning, in what Didion calls the “vortex”—her term for those sudden, engulfing swells of memory that can be triggered by the most ordinary stimuli.

A familiar song, a glimpse of a place she and John visited, even a stray thought can pull her irresistibly into a recollection so vivid and consuming that it leaves her momentarily paralyzed in grief. “The way you got sideswiped was by going back,” she notes. To “go back” and to indulge memory is to risk being sideswiped by the reality of loss all over again.

In one instance, Didion finds herself frozen before a closet, struck by the sight of her late husband’s shoes, the very ones she can’t bear to part with; the mundane act of opening a closet becomes a portal to anguish. This intrusive memory phenomenon is well-known in grief (and shares features with traumatic flashbacks). In Didion’s case, positive memories can be just as triggering as painful ones, because every happy reminiscence carries the sting of irreversibility.

The memoir illustrates how grief disrupts the linear timeline: past moments with John replay in Didion’s mind with technicolor immediacy, coexisting with the present in a way that defies the normal flow of time.

Time Distortion and Nonlinear Structure

Didion’s narrative structure itself mirrors this temporal distortion. Rather than recount events in strict chronology, Magical Thinking loops and circles back. Key scenes such as the night of John’s death are relived multiple times in the text, each iteration zooming in on different details or emotional realizations. Early on, we get a spare journalistic account of that night; later, we revisit it with additional layers of insight or context.

This recursive structure formalizes what grief does internally. The mourner replays the traumatic moment, each time hoping for a new understanding or simply to master it through repetition. Didion obsesses over medical records and timelines, dissecting phrases like “fixed dilated pupils” with journalistic rigor. These clinical details, painfully inadequate in conveying the death of someone beloved, become objects of fixation. Through this, she tries to impose narrative control on an experience that has no logic.

Memory in this book is thus double-edged. It is the treasury of all she shared with John: forty years of marriage, conversations, trips, and inside jokes, which she does not want to lose. Yet it is also the source of acute pain and disorientation, since every memory underscores his absence. She writes of being caught off guard by recollections and then struggling to reorient to a world in which that remembered moment is no longer retrievable in reality.

There is a powerful passage where Didion describes how, after John’s death, she would encounter something interesting in the news or think of an idea and reflexively reach to tell John, then freeze as she remembered he was gone. In those instances, memory isn’t a comfort; it’s a knife-twist, reminding her that the person with whom those memories were created is no longer there to share them or to validate the shared history that formed a core of her identity.

Identity, Shared Memory, and the Fear of Forgetting

Didion notes that losing John meant losing the one person who remembered certain events of her life as she did, the only other witness to their private world. Thus, memory and identity are intimately linked in the memoir. As long as John was alive, Didion’s memories were living, dynamic, and constantly augmented by their ongoing life together, mutually reinforced by each other’s recollection.

After John’s death, her memories feel more like fragile artifacts she alone is responsible for carrying. This realization contributes to what Didion calls “mourning for oneself”: in grieving her husband, she is also grieving “the loss of the way things were, the person she herself was when John was alive.”

The memoir emphasizes how mourning involves memory, and specifically, mourning involves the fear of memory’s decay. Didion feared “letting go” of grief in part because it felt like letting go of memory, of the vividness of John’s presence in her mind. Who was she, if not the wife who remembered John? The role of family relationships in configuring identity becomes painfully clear to her after his death. She had been one half of a partnership for so long that navigating the world alone, even the simple act of reading a newspaper without being able to discuss it with him, calls into question her very self.

Memory Work as Meaning-Making

From a psychological perspective, Didion’s experience underscores the notion that part of grieving is redefining one’s relationship to the deceased. Classic theories urged complete detachment, but more recent grief models advocate for continuing bonds, finding a healthy way to maintain an inner connection with the lost loved one while acknowledging their physical absence.

Didion does exactly this through memory. Over the year, she gradually shifts from needing John to literally return to integrating him as an internal presence. We see this transformation in how her use of memory evolves. Early on, memories ambush her (the vortex), leaving her feeling out of control. She tries to avoid those triggers; for example, she cannot yet face going to the places they frequented together, fearing the vortex.

But as time progresses, Didion begins to actively curate her memories of John. She sifts through photographs, recalls stories of their travels, and even reads his old letters or books. These acts become a way of communing with him in his absence, consciously and more calmly. Writing the memoir itself is the ultimate act of memory to preserve them: Didion putting down the details of their last days, of her grief, of who John was. And in doing so, she is performing what grief counselors might call “meaning-making” or narrative reconstruction. She is weaving the chaotic strands of the past year into a story that she can hold onto and understand.

The Trauma of Ordinary Instants

The concept of time is also manipulated in Magical Thinking to reflect Didion’s altered perception. In grief, time can simultaneously freeze and race. Didion remarks that the year after John’s death seemed to both drag on interminably and yet disappear in a blink, a contradiction common in bereavement accounts. Her sense of dates and normal temporal landmarks was upended (at one point, she forgets what month it is or is startled by the change of seasons).

The memoir’s fragmentary and looping structure, with fragments of poetry or previous writings inserted, echoes this broken chronology. Didion even includes the exact timestamps of certain hospital events or phone calls, suggesting how obsessively her mind latched onto temporal details as anchor points in a sea of confusion. It’s as if, by pinning down when things happened, she hoped to restore order.

Memory, for Didion, is also tied to the physicality of grief. She notes how grief affected her body, the waves of dizziness, the feeling of being faint or disembodied when a memory struck. The quote “Life changes in the instant. The ordinary instant” that opens the book is returned to later when she describes how an ordinary sight or sound can instantly transport her to a different time, knocking the wind out of her.

Didion even explicitly asks herself, “What could I have done?” and “What if I had been in Los Angeles instead of New York—could it have been different?” engaging in counterfactual, time-bending thoughts common in both grief and trauma as one tries to undo the event mentally. She eventually works through these unanswerable questions to the point of accepting that nothing would have changed the outcome.

“Magical Thinking”: Illusion, Denial, and Control

The very title of Didion’s memoir announces magical thinking as its governing motif. In the anthropological sense, magical thinking is the belief that one’s thoughts or actions can influence events that are objectively beyond one’s control, a kind of superstition or primitive logic found in many cultures and in childhood cognition. For Didion, magical thinking began to define her mindset in the aftermath of loss: a desperate, if momentary, belief that she could somehow undo the reality of her husband’s death.

Didion was stunned to observe herself lapsing into ritualistic and illogical behaviors, all oriented around an unstated hope that John might return. She would not donate his shoes and clothes, because how could he come back with nothing to wear? She was uneasy about the autopsy, irrationally reasoning that “whatever had gone wrong was something simple… easily fixed,” as if a medical examiner might find a reversible flaw.

Cultural Delusions About Control

The memoir is candid about these “quiet delusions,” tracing how they ebbed and flowed over the year. For months, “‘bringing him back’ had been… my hidden focus, a magic trick,” she confesses; even after realizing this intellectually, “Seeing it clearly did not yet allow me to give away the clothes he would need.”

Over the course of the memoir, we see magical thinking gradually recede as Didion confronts the unavoidable truths about mortality. A turning point comes when she reads the coroner’s autopsy report on John’s heart failure. The clinical finality of terms like “fixed dilated pupils” and the sheer physiological fact of a major coronary artery completely occluded force her to accept that nothing she did or didn’t do caused his death. “It was only after the autopsy report did I stop trying to reconstruct the collision, the collapse of the dead star,” she writes, using the metaphor of a star that had already burned out long before its light disappeared from view.

Letting Go

In finally admitting that John’s death was beyond anyone’s control, Didion releases the last hold of her magical thinking. She recognizes a broader cultural fallacy at the same time:

“I realize how open we are to the persistent message that we can avert death. And to its punitive correlative: that if death catches us, we have only ourselves to blame.”

Here she indicts the modern ethos that encourages constant self-optimization, as if eating the right foods or taking the right medicine could grant immortality—an attitude that can slyly shame the bereaved (did we miss something? do something wrong?). Didion’s journey through magical thinking, then, is not just a personal quirk; it reflects our collective struggle of surrendering to the fact of death’s randomness.

By the memoir’s end, Didion has stopped waiting for John’s return. In a tacitly heart-wrenching moment, she packs up his shoes to give away, the very shoes she once so fiercely protected. It is a symbolic act of “relinquishing the dead,” acknowledging that to “keep them dead” is an act of love too, because it allows the living to go on living.

Further Reading

The Anatomy of Grief by Peter D. Kramer, Slate