Explore This Topic

- The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion: A Deep Literary Analysis

- Why Joan Didion’s Prose Style Works in The Year of Magical Thinking

- Grief, Memory, and Magical Thinking: Themes in Didion’s Work

- 8 Striking Quotes from The Year of Magical Thinking (And What They Reveal)

- Books Like The Year of Magical Thinking: Grief Memoirs That Go Deeper

- What Didion Doesn’t Say: The Historical Context Behind The Year of Magical Thinking

The experience of losing a loved one is one of life’s few certainties, yet the manner in which that loss is felt, interpreted, and recorded varies with each individual. Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking (2005) stands as a touchstone in the literature of bereavement—a meticulously observed, unsentimental chronicle of the year following her husband’s sudden death, rendered in prose at once austere and precise. Her work remains notable not only for its emotional restraint but also for the intellectual rigor with which it examines mourning as both event and process.

Yet the register of grief is never singular. While Didion’s narrative has endured for its clarity and control, many readers find themselves drawn toward memoirs that articulate sorrow from other perspectives: the loss of a parent, a child, a sibling, a friend, or even an entire community; narratives that foreground cultural or spiritual frameworks; and voices that diverge in tone or temperament from Didion’s carefully maintained remove.

What follows is a curated selection of contemporary grief memoirs that respond to these varied expressions of mourning. Organized thematically, these works do not simply echo the concerns of Didion’s book but extend and complicate them—each offering a distinct vantage on memory, loss, and the act of continuing.

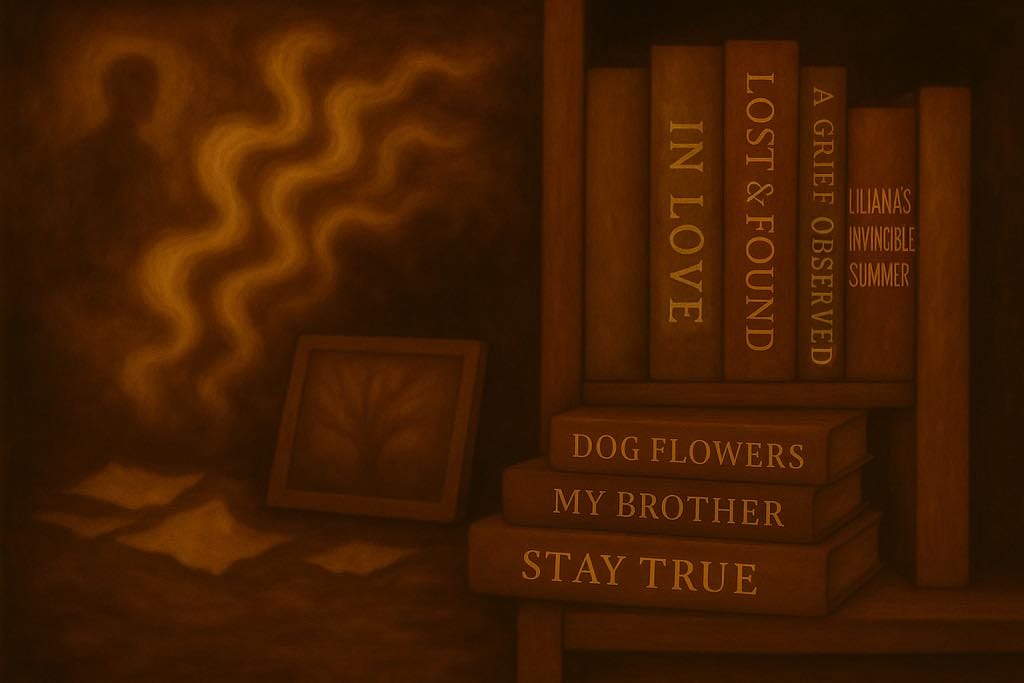

Love and Loss: Memoirs of Spousal Grief

Memorial Days by Geraldine Brooks

Memorial Days (2023) by Geraldine Brooks opens at the precise instant her world falls apart—a late-night phone call brings the news that her husband, historian Tony Horwitz, has collapsed and died suddenly while on a book tour. Brooks, a Pulitzer-winning novelist and journalist, renders the opening scenes in urgent, clipped present-tense narration, capturing the immediacy and disorientation of that moment. What unfolds is a restrained yet resonant account of mourning, an eloquent reflection on love, absence, and endurance in a world without religious consolations.

Like Didion, Brooks finds herself thrust into widowhood without warning, yet her approach highlights different facets. She exposes the harsh and impersonal mechanisms that often confront the bereaved, from the dehumanizing language used in emergency rooms, where her husband is referred to in abstract terms, to the bureaucratic demands that offer little room for mourning in the immediate aftermath.

Memorial Days unfolds across two temporal strands: the immediate aftermath of Horwitz’s sudden death in 2019 and a later period, three years on, when Brooks retreats to a remote Australian island. There, in relative isolation, she grants herself permission to fully enter the space of mourning, a process that echoes the structured rituals of traditional grief, now often absent in secular life. This retreat becomes less a gesture of escape than a calculated pause, a setting aside of time in which sorrow is neither minimized nor postponed.

The memoir is both an elegy to a beloved husband and an inquiry into how one navigates a life after profound loss. Like Didion, she documents sorrow with clear-eyed discipline, yet she also ventures into the metaphysical, drawing on her Jewish faith to explore frameworks for life’s endurance and purpose. The resulting narrative offers a resonant counterpoint to Magical Thinking, an exploration of sudden spousal loss transformed by cultural perspective, delayed reckoning, and a profound refusal to sentimentalize.

In Love: A Memoir of Love and Loss by Amy Bloom

If Brooks’s story is about the shock of sudden loss, Amy Bloom’s In Love: A Memoir of Love and Loss (2022) charts a profoundly different trajectory: one in which death is anticipated, negotiated, and chosen. When her husband, Brian, is diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s, the couple makes the painful decision to pursue an assisted death in Switzerland. What follows is not only a journey across continents but also a reckoning with the ethical, emotional, and existential dimensions of saying goodbye while love is still present and mutual recognition still possible.

Bloom writes with unsparing candor and fierce tenderness, documenting the procedural labyrinth of assisted dying and the slow erosion of Brian’s memory and personality. This is far from a typical widow’s memoir; it’s a love story told in reverse, through the prism of a looming end that the couple actively navigates. What distinguishes In Love is its refusal to romanticize or dramatize. Bloom treats euthanasia neither as taboo nor as a political statement, but as the deeply personal solution to an impossible dilemma, a choice rooted in love and carried out with dignity.

Bloom, a novelist known for her rich, character-driven stories, brings gravitas and compassion to questions most of us hope never to face. Her language is clear, unsentimental, and emotionally grounded. Unlike Didion’s retreat into magical thinking, Bloom faces grief head-on, contending not with the shock of loss but with its slow, visible approach. Her exploration of anticipatory grief—of grieving not only the person who will be lost but the gradual disappearance already underway—makes this book uniquely affecting.

And yet, despite the gravity of its subject, In Love does not dwell in despair. What shines through is the intimacy between two people determined to meet death with agency and mutual respect. Bloom recounts Brian’s insistence on preserving his autonomy, choosing to end his life before the illness could strip him of his identity. Her memoir broadens the emotional and ethical range of grief literature by offering a vision of love rooted in the strength required to part with intention and grace.

Parental Loss and the Search for Identity

Losing a parent can upend one’s sense of self, and two recent memoirs explore this truth from very different angles.

Lost & Found by Kathryn Schulz

In Kathryn Schulz’s Lost & Found (2022), the acclaimed New Yorker writer examines the eerie timing of losing her father just as she fell in love. Schulz’s father, a charming and erudite man in his 70s, died after a long illness, a death she notes was sad but “not a tragedy,” coming at the natural end of a life well-lived.

Eighteen months before his passing, Schulz met the woman who would become her life partner, and thus her memoir braids together two narratives: one of grief for a beloved parent (the “Lost”) and one of the joy of finding a partner (the “Found”), with a short coda (“And”) reflecting on how these experiences intermingle. What makes Lost & Found extraordinary is not the events themselves; as Schulz wryly points out, there’s nothing especially uncommon about a person in midlife experiencing both death and love. Rather, it is her reckoning with the very concepts of loss and discovery that elevates the book.

Schulz has a nimble, inquisitive mind that ranges from etymology to literature to cosmic coincidence. Early on, she muses on why we use the verb “lose” for death, tracing it to ancient words for perishing and separation. Didion’s Magical Thinking, too, had moments of larger inquiry (for example, questioning medical notions of grief stages), but Schulz pushes further into abstraction, crafting a work of dazzling intellect grounded in deeply felt experience.

The prose moves fluidly from tender scenes (sitting at her dying father’s bedside or feeling the spark of new love) to broader insights on how every loss in life may carry an unexpected find, and vice versa. Schulz explores this duality with nuance, showing how the act of revisiting grief can also unearth moments of unexpected clarity or joy. For anyone who appreciated Didion’s incisive mind but wants a dose of warmth and optimism alongside the sorrow, Schulz offers a beautifully balanced perspective on the cycles of life.

Dog Flowers by Danielle Geller

In Dog Flowers (2021), Danielle Geller also loses a parent (her mother), but here the journey of grief becomes a journey into heritage, identity, and understanding a life marked by hardship. Geller, a Navajo writer, was largely estranged from her mother, Laureen, who struggled with alcoholism and homelessness. When Laureen dies, Geller inherits a trove of her belongings: eight suitcases stuffed with diaries, letters, photos, scraps of a troubled life. From these fragments, Geller assembles not just her mother’s story but also her own.

Dog Flowers is subtitled “A Memoir, an Archive,” and indeed the book’s structure blends personal narrative with archival documents and images. This narrative technique stands in contrast to Didion’s, who focused almost exclusively on her own interiority in Magical Thinking. Geller instead turns her gaze outward and backward, reconstructing her mother’s youth on the Navajo reservation and her turbulent adulthood while interweaving Geller’s childhood memories and her attempts to reconnect with family on the reservation after Laureen’s death.

The grief here is not just for the mother who died but for the mother Geller never fully knew and the cultural identity she herself fears she’s lost touch with. Dog Flowers is unflinching about the familial pain of addiction, abuse, and intergenerational trauma, yet it’s driven by a desperate tenderness. Where Didion intellectualizes, Geller excavates (literally sifting through artifacts) to bridge a gap between mother and daughter, past and present.

Because of this, Geller also explores what it means to be Navajo and “home.” By the memoir’s end, her grief has led her to perform ceremonies on ancestral land and to see her mother’s life in a more compassionate light. Dog Flowers thus complements Didion by adding dimensions of cultural identity and reconciliation to the work of mourning. It’s a powerful story about how losing a parent can trigger a search for oneself and how assembling the pieces of someone’s story can be a final act of love.

The Unthinkable Loss of a Child

Few losses are as unfathomable as the death of one’s child. Two memoirs, one written during a child’s dying and one written after, explore this extreme terrain with courage and insight.

The Still Point of the Turning World by Emily Rapp Black

Emily Rapp Black’s The Still Point of the Turning World (2013) recounts the journey of her infant son Ronan’s brief life and impending death. At just nine months old, Ronan was diagnosed with Tay-Sachs disease, a rare genetic disorder that is always fatal, typically by age three.

Rapp, a writer and former divinity student, suddenly found herself a mother with no future to imagine for her child. Rather than turn away from this cruel reality, she confronted it head-on in writing. In fact, the memoir ends while Ronan is still alive, because Rapp completed her story before his death; her act of writing was itself a way to grieve in advance.

This perspective of anticipatory grief distinguishes Rapp’s book from Didion’s Magical Thinking. Didion dealt with shock and retroactive longing, whereas Rapp lived in an ongoing tragedy, balancing intense present love with the knowledge of looming loss. Her prose is at once precise and profound. She draws on philosophy, poetry, and theology (the title itself references a T.S. Eliot poem) to make sense of the existential cost of such love, the price paid for loving someone destined to die so young.

An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination by Elizabeth McCracken

Elizabeth McCracken’s An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination (2008) starts where no parent ever wants to: with a stillbirth. McCracken was nine months pregnant with her first child when she learned that her baby boy had died in utero just before labor. In this slim memoir, she chronicles that horrific loss and the year that followed, including a subsequent pregnancy that brought her a healthy second baby.

McCracken, a novelist by trade, writes with a remarkable blend of candor, dark humor, and tenderness. While the subject is unimaginably sad, her voice is not mournful 100% of the time; she finds sparks of wit and joy within the darkness. She describes moments like picking out tiny coffin decorations with a sort of wry, self-aware astonishment at the absurdities grief forces upon us.

Crucially, Exact Replica is also a love story, not just of McCracken’s love for her lost baby, whom she calls Pudding, but also for the second son born a year later. The narrative juxtaposes the two pregnancies: one ending in heartbreak, the other in hope. This structure gives the book a gentle cathartic arc, from utter despair to a bittersweet happiness.

Yet McCracken never suggests that a subsequent child “replaces” the one who died (hence, the title). The second baby is a new, beloved individual, while the first remains an exact replica of her imagination, forever a perfect dream that almost was. Indeed, McCracken’s novelist sensibilities shine in the lyrical quality of her reflections and the vividness of her memories. She offers consolations without clichés, acknowledging that nothing can erase the pain, but life can still surprise you with grace.

Compared to Didion, McCracken is more intimate and openly emotional, though never saccharine. Didion kept a cool control over her narrative, whereas McCracken at times lets herself laugh through tears or marvel at the sadness and love coexisting in her story. Reading Exact Replica alongside Magical Thinking, one appreciates how even the most private sorrows can be rendered in literature with honesty and even wit. Both books ultimately affirm Didion’s famous line that “life changes fast,” but McCracken adds that it can also continue, carrying new life, new stories.

Siblings: Bonds and Bereavements

The death of a sibling can be a particularly complex grief, tied up with childhood memories, family roles, and often the “what if” of unrealized futures. Two memoirs, written decades apart, explore sibling loss in searing, nuanced detail.

Liliana’s Invincible Summer by Cristina Rivera Garza

Cristina Rivera Garza’s Liliana’s Invincible Summer (2023) is subtitled “A Sister’s Search for Justice,” and that immediately signals how this grief memoir differs from most: it doubles as an investigative quest. Rivera Garza, one of Mexico’s renowned novelists and poets, lost her younger sister Liliana in 1990. Liliana was murdered at age 20 by an ex-boyfriend in an act of femicidal violence, a tragedy as much a product of cultural forces as individual fate.

For thirty years, the killer evaded capture, and the case went cold. Eventually, Rivera Garza undertook the painstaking task of retracing every detail of her sister’s life and final days, driven by a need to reconstruct the truth of who Liliana was and perhaps even flush out new leads. The result is a memoir that defies categorization, blending personal testimony, archival research, and investigative writing into a singular work of remembrance.

Liliana’s Invincible Summer unfolds as a meticulous collage: Rivera Garza scours diaries, interviews friends, consults case files, and walks the actual paths her sister took in her final days. Photographs, letters, and even Liliana’s own writings are woven into the text, giving Liliana a voice. Rivera Garza not only mourns Liliana, she challenges the societal epidemic of violence against women that took her sister’s life.

How does this resonate with readers of Didion? While Didion’s grief was private and domestic, Rivera Garza’s is inherently political. Yet there are points of connection: Didion wrote of her “vortex” of memories around her husband’s death, sifting through hospital records and recollections to make sense of senseless loss. Rivera Garza undertakes a similar sifting, though her vortex is one of forensic and emotional data spanning decades.

My Brother by Jamaica Kincaid

In Jamaica Kincaid’s My Brother (1997), grief takes on a different complexity: that of losing someone with whom one had a difficult, even ambivalent, relationship. Kincaid’s younger brother, Devon, died of AIDS in 1996 at the age of 33. In this memoir, Kincaid examines her brother’s life and death with unblinking honesty.

Devon had lived in Antigua (their birthplace) in poverty, struggled with drug use, and had a distant relationship with Jamaica, who by then had long settled in the United States. Kincaid does not sentimentalize her brother or pretend to a closeness they didn’t have. Instead, she renders her brother with unflinching honesty by capturing his flaws, struggles, and humanity.

The memoir unfolds partly as Kincaid’s personal journey and partly as a meditation on their family. She scrutinizes her own responses, at one point admitting she felt more sorrow watching Devon’s once-handsome face deteriorate than she initially felt at the news of his illness. She ponders the injustice of AIDS and the social stigma attached to it at the time, and she reflects on the distances (geographical, emotional) that separated her from her siblings. In the end, though, she manages to forge a kind of posthumous intimacy with Devon through writing.

Kincaid’s grief is tangled up with guilt, resentment, and yearning, a far cry from Didion’s relatively straightforward sorrow for a deeply loved spouse. And yet, both writers share a refusal to indulge in easy comforts. For a reader who appreciated the emotional restraint and insight of Magical Thinking, My Brother offers a different flavor of restraint. It challenges the idea that grief always brings people closer; sometimes, it magnifies the distances and forces you to reckon with what never was.

Beyond Family: Grieving Friends and Communities

Not all our profound losses are of relatives or partners; some are of chosen family or entire communities. In this final cluster, we look at two memoirs that venture beyond the traditional family unit: one tracing the loss of a dear friend and another mourning multiple deaths in a community.

Stay True by Hua Hsu

Hua Hsu’s Stay True (2022) is a memoir of friendship, art, and the coming-of-age that was abruptly shattered. Hsu, now a staff writer at The New Yorker, was a college student at UC Berkeley in the mid-1990s when he befriended Ken, a Japanese American classmate seemingly his opposite in tastes and temperament. Just as the two young men were forming a deep, if unlikely, bond, Ken was killed in a random carjacking.

The murder of a 20-year-old for no reason at all left Hsu unmoored, grappling not only with grief but also with guilt (common in survivor’s grief) and the existential questions of youth. Stay True is Hsu’s attempt, decades later, to make sense of that loss and memorialize his friend. Central to Hsu’s meditation is the question of authenticity, how one learns to inhabit their own identity in the wake of tragedy, and how to represent someone else’s life with integrity and care in writing.

The narrative is threaded with music and pop culture, making it a poignant Gen-X elegy. Stylistically, Hsu writes in a straightforward, reflective manner. He doesn’t indulge in overwrought sentiment; instead, the power lies in the questions he asks and the details he preserves. This self-awareness about storytelling and memory gives Stay True a philosophical kinship to Didion’s approach.

Didion, too, was concerned with the accuracy of memory and the narratives we construct around death. In Magical Thinking, she scrutinized every detail of her husband’s final days, fearful of getting it wrong or losing the truth of him. Hsu carries a similar vigilance for his friend.

Men We Reaped by Jesmyn Ward

By contrast, Jesmyn Ward’s Men We Reaped (2013) paints grief on a broader canvas, that of an entire Black community in the American South ravaged by tragedy. In a span of four years, Ward lost five young men who were close to her: among them her younger brother, Joshua, as well as cousins and friends, all from her rural Mississippi hometown. The causes were varied (car accidents, suicide, drug overdose, violence), but underlying them, Ward discerned common threads of poverty, racism, and hopelessness that stalk young Black lives.

Men We Reaped is both deeply personal and socio-political. Ward, a two-time National Book Award-winning novelist, writes with language that is lush and evocative, steeped in the sights and sounds of the Gulf Coast, yet it’s also unsparing in truth-telling. She mourns, too, the slow violence of economic struggle that wore her family down. Yet alongside the anger and sorrow, Ward celebrates the lives of those she lost, rendering each friend or relative with loving detail and acknowledging their flaws without judgment.

For readers of Didion, Men We Reaped offers both a comparison and a contrast. Like Didion, Ward engages in a form of reporting, such as gathering facts, interviewing relatives, and contextualizing each passing. Ward even quotes historical figures (the title comes from a Harriet Tubman quote about reaping the harvest of war’s dead). Both authors ask “Why?” after sudden deaths. But where Didion’s inquiry stayed intimate and somewhat detached, Ward’s “Why?” is aimed at America itself. In scenes describing the community coming together after each funeral, Ward finds a resilient beauty in the solidarity of her people. To read Ward’s memoir is to understand grief as a social experience as well as a personal one.

###

Each of these memoirs goes beyond the scope of Didion’s Magical Thinking in its own way. All of them refuse easy consolations and instead dig deeper into philosophical questions, cultural contexts, historical injustices, or the labyrinth of memory. Reading them, we encounter grief in its myriad forms.

Some of these writers, like Schulz and McCracken, ultimately find a measure of hope or meaning blooming alongside loss. Others, like Rivera Garza and Ward, turn their sorrow into a rallying cry or a work of witness. All treat grief not as a passive state but as an active journey, one that involves searching, questioning, fighting, remembering, and, above all, writing.

Joan Didion wrote, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” These memoirists tell their grief stories in order to live with what they have lost, and in doing so, they give us not just mirror reflections of Didion’s experience but new windows into the human condition. For readers seeking books like Didion’s, these memoirs offer companionship on the long road through mourning, each illuminating a stretch of terrain that Didion had not traversed, while offering steadfast company for those navigating their own.

Further Reading

Best books for overcoming grief, but are not self help, more of a hidden theme? on Reddit