My Reading Note

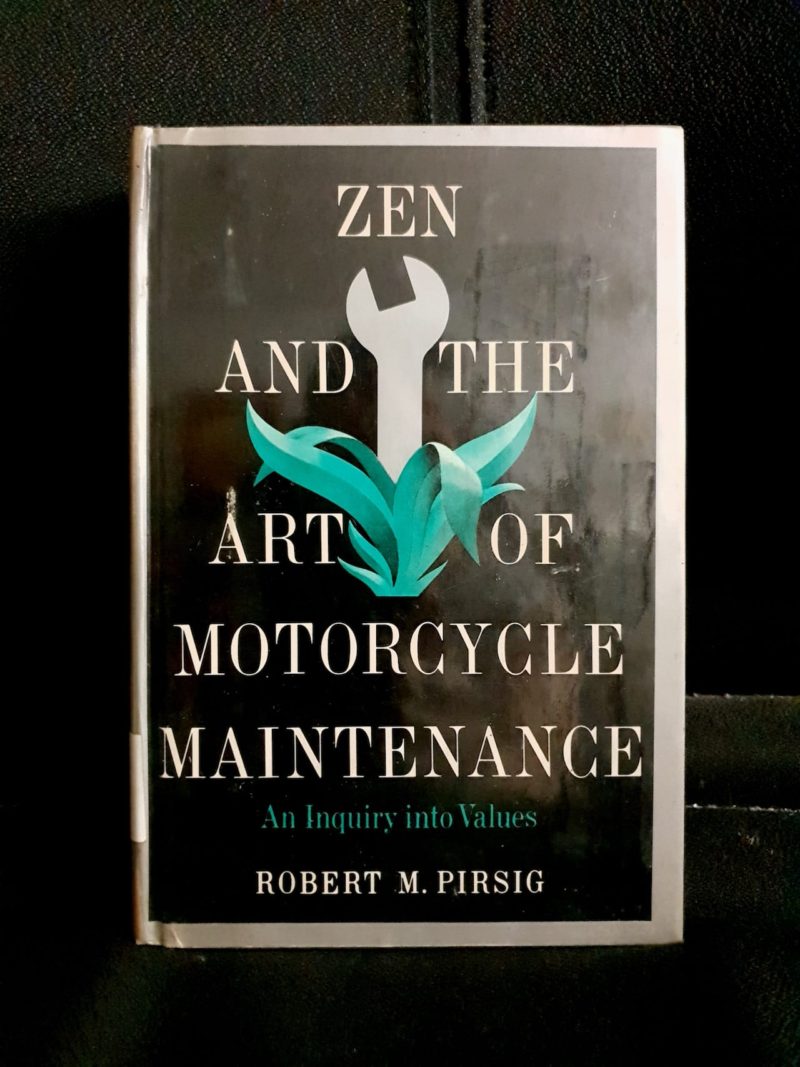

I bought this book for its cover, with its dandelion design on a dirty white field. I was prepared for Barnes’s themes, but not for the novel’s effect. It stayed with me because of its technique: a narrator’s voice assembling a version of history he can live with.

Memory in Julian Barnes’s The Sense of an Ending (2011) acts as a curator of disgrace. The novel grants its narrator, Tony Webster, a voice of fastidious recollection—a voice that sorts, labels, and displays the artifacts of a life with the calm authority of a museum guide. The narration is the exhibit, a collection arranged for internal consistency rather than verifiable fact. This curated past, presented with such declarative ease, forms the book’s primary aesthetic and philosophical gesture. Barnes constructs an exhibition to be doubted.

This review examines the technical methods of this narrative curation. Tony’s retelling is an act of retrospective construction, where each verbal hedge and qualified assertion contributes to a defensive structure. Through clear, controlled prose, a sustainable self is produced from the intolerable materials of regret and failure. Barnes’s stylistic control ensures the preservation of the specific self Tony requires. The novel derives its authority from a precise correspondence between its form and its aim.

My analysis focuses on the narrative voice as the novel’s primary artistic achievement. Other elements, such as the philosophical musings on time, or the portrait of English middle-class life, are secondary to the technical feat Barnes accomplishes through Tony’s recounting.

I focus here because the voice is the novel’s argument. Its construction makes abstract ideas about memory and regret physically felt.

The Anatomy of a Conjured Voice

The novel begins with a direct statement about memory’s failures. From there, Barnes constructs Tony’s voice with conversational assurance and saturates it with the qualifiers of casual recall: “I suppose,” “probably,” “as I remember it now.” These phrases serve specific instruments. They build a narrator whose veneer of candor secures belief. This constructed stability exists to be undermined.

I read these qualifiers as a form of narrative sleight-of-hand. Each “I think” introduces a tremor into the story’s foundation. The tremor of his voice as he recalls them reveals more than the events he describes.

The prose is clean, precise, and deceptively simple, a stylistic choice that mirrors Tony’s own desire for a tidy, managed history. Barnes uses this clarity as a contrast agent. When the cracks appear, such as a dissonant detail, a letter with delayed contents, or the chilling calm of Veronica, they create stark friction against the orderly backdrop of Tony’s narrative.

This is Barnes’s finest trick. He doesn’t write an obviously “unreliable” narrator; he writes a convincing one. The betrayal is slower, more profound. We are not lied to; we are shown how lying to oneself sounds when it’s perfectly sincere.

The principle is this: the more a truth threatens a narrator’s current sense of self, the more intensely they will reconstruct the past. Tony’s memory does not blur events. It redraws them to create a bearable account. The document from Veronica’s mother then acts as a mirror for this constructed story, a reflection that reveals its fundamental instability.

Memory as Active Construction, Not Passive Recall

The plot turns on a delayed revelation: a letter and a bequest that contradict Tony’s long-held understanding of his youth and his friend Adrian’s suicide. A lesser novel might use this as a simple twist, a corrective to the record. Barnes does something more sophisticated and devastating. The new information does not replace Tony’s story but exposes its fundamental nature.

Tony is not only remembering his life but also actively authoring it in the present tense portion of his narration (the framing tense when he reflects on his life). His account is a performance of retrospective projection, where the “haunting” occurs in the gap between the life lived and the life narrated. This structural unreliability is synthesized with the psychological concept of narrative identity—the theory that the self is a story we continually write and edit.

The driving force of the haunting is not malice but a profound, unconscious need for psychic survival. Tony’s unreliable narration is a corrective mechanism against a past he finds morally and emotionally unbearable. His younger self’s casual cruelty, his failure of empathy toward Adrian and Veronica, and his own mediocrity are facts his present self cannot integrate.

The Novel’s Proposition on Narrative Voice

A common thread in engagements with this book is a search for the stable, objective history—the “real story” of Adrian, Veronica, and the past. Readers often attempt to assemble the facts Tony omits or distorts, to solve the puzzle.

I contend that this instinctive puzzle-solving misapprehends Barnes’s aim. The novel is not a cryptogram hiding a factual truth. It is a demonstration that for this consciousness, a factual truth is not available; there is only the sustained act of its composition.

This positions the book within a specific literary tradition, one that extends the modernist investigation into subjective consciousness, but strips it of aesthetic grandeur. Where a narrator like Marcel Proust’s in In Search of Lost Time constructs a majestic, sensory cathedral of memory, Tony builds a sensible suburban annex. His is an unreliability of administration, not artistry. The book’s achievement is to render this bureaucratic self-deception with profound tragic clarity.

A Corrective View on Narrative Closure

A corrective analysis must address the expectation that Tony, upon receiving new information, achieves clarity or redemption. The novel’s devastating power stems from its denial of this catharsis. The haunting finds no resolution, only a lasting reconfiguration.

This necessitates a contrastive evaluation. Where a narrator like Ford Madox Ford’s Dowell (The Good Soldier, 1915) uses unreliability to obfuscate his own desires, Tony uses it to construct a viable self. Dowell’s deception is a shield; Tony’s is a crutch. The “sense” of an ending Tony reaches is not understanding, but the grim accommodation one makes with a permanent, haunting presence.

The book’s final line about the “accumulation” of life is often read as wisdom. I hear it as the sound of the ghost settling into a new, permanent room in Tony’s psyche. He hasn’t uncovered the truth but has simply furnished a more comfortable prison for his illusions.

The Sense of an Ending renders a definitive portrait of a mind at work on its own biography. Barnes commits to a voice formed by its own needs, a formal decision that becomes the novel’s entire argument. Because of this commitment, the novel shows how such a voice builds, sustains, and justifies its own account. In these terms, the novel does what it sets out to do. It follows a single rule: a man’s voice will arrange his history to serve his present requirements. Barnes commits to this rule without hesitation, and the prose proves it. With this novel, Barnes has given us a definitive study in the continuous work of editing a life.

The Anatomy of the Best Book Cover Designs: What Makes a Book Cover Stand Out?

These two posts from the archive provide the foundational framework for a complete analysis of Barnes’s work. “Unreliable Narrator” defines the specific narrative device that structures the entire novel and dictates the reader’s role. In addition, the article on cover design articulates the visual logic for a cover like this one, which I find particularly effective. Read it also to understand the concept of the cover behind my analysis and why it caught my eye.

Selected Passage with Analysis

Another detail I remember: the three of us, as a symbol of our bond, used to wear our watches with the face on the inside of the wrist. It was an affectation, of course, but perhaps something more. It made time feel like a personal, even secret, thing. We expected Adrian to note the gesture, and follow suit; but he didn’t.

Page 6, The Sense of an Ending by Julian Barnes

The watch ritual perfectly encapsulates the novel’s inquiry into self-mythology. The trio of Tony, Colin, and Alex’s performative gesture is a hollow claim to control time, mistaking a stylistic rebellion for a philosophical one. It is an act of curation, not conviction, designed to manufacture a shared identity they believe marks them as profound.

Adrian’s rejection of this symbol is critical. His refusal to participate exposes the gesture’s intellectual poverty. It establishes him as a figure of authentic, uncompromising thought, which the group’s affected posture cannot absorb. This remembered slight becomes a foundational stone in Tony’s later narrative — a story built to rationalize why Adrian remained forever outside their grasp, and why his own life followed a safer, lesser course.

Therefore, the detail is not mere recollection but evidence of Tony’s narrative architecture. He does not remember the watch; he remembers his group’s failed attempt to use it as a token of belonging. The memory is polished into a relic that explains Adrian’s confounding superiority and justifies Tony’s own enduring sense of having lived on the wrong, more ordinary side of a profound divide.

Further Reading

Self-deception: The Sense of an Ending [PDF file] by Yueqing Yuan, Shanghai International Studies University

The Sense of an Ending, explained [spoilers] by andrewblackman.net

The Sense of an Ending on The Booker Prizes

The Sense of an Ending – Julian Barnes on Reddit