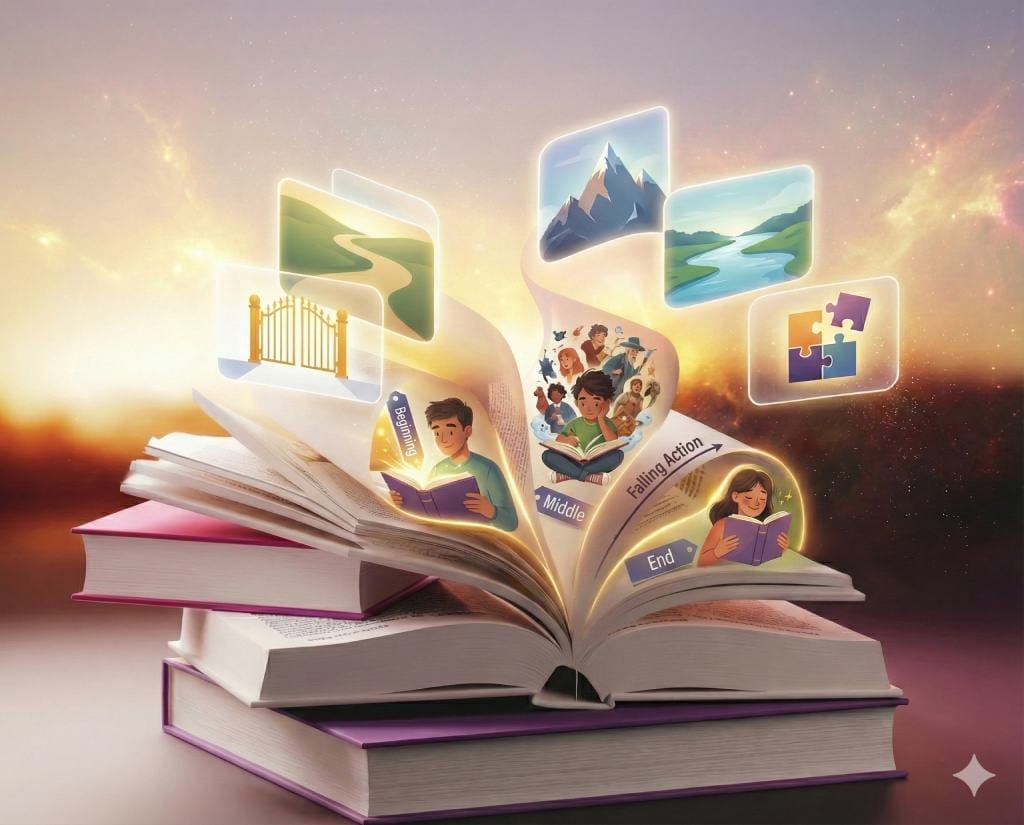

When we talk about “narrative structure,” the conversation usually defaults to the writer’s perspective: the blueprints, the beat sheets, the three-act outlines. We treat structure as a manufacturing template, a set of rules authors follow to assemble a product. But for the reader, structure is something entirely different. It is not a template to be filled, but a sequence to be experienced.

Structure is the invisible architecture that guides our perception. It dictates the relationship between events, the order in which they appear, and the way we, as readers, make sense of that order. It determines not just what happens, but how it feels to discover it.

This guide is not an instruction manual on how to write; it is an exploration of how to read. By understanding how stories are built, we gain access to a richer, more layered experience of the books we love. We stop asking “What happens next?” and start understanding why the story is moving the way it is.

How Narrative Structure Directs the Reader’s Perception

If you ask a casual reader to define a story, they might describe it as a straight line: Event A leads to Event B, which leads to Event C. This is the “chronology” of the story. However, narrative structure is rarely a straight line. It is the calculated management of emphasis, sequence, and movement.

When we read with an awareness of structure, we distinguish between the story (what happened) and the plot (how it is presented). We begin to perceive the story as an intentional construction. We notice that the author has chosen to place a specific memory in Chapter 3, rather than Chapter 10. Why? Because the placement changes the meaning.

Structure allows the reader to perceive three essential dimensions of a text:

- Emphasis through arrangement

- Sequence and meaning

- Movement and velocity

Emphasis Through Arrangement

In a 300-page novel, for example, not all moments are created equal. Structure is the tool authors use to tell the reader what matters.

- Space allocation: If an author devotes twenty pages to a single dinner conversation but summarizes three years of travel in a single paragraph, the structure is shouting at you. It is telling you that the nuance of that conversation is structurally more significant than the events of the travel.

- Positional emphasis: Beginnings and endings are positions of power. A detail placed at the very end of a chapter carries more emphasis than a detail buried in the middle of a paragraph. The structure highlights specific details by giving them “pride of place.”

Sequence and Meaning

The order in which we learn information changes how we judge it. Consider a story about a theft.

- Scenario A: We learn a man is starving. Then, we see him steal a loaf of bread.

- Scenario B: We see a man steal a loaf of bread. Then, we learn he is starving.

- Scenario C: We see a man steal bread. We never learn why.

The events are identical in all three scenarios, but the structure—the sequencing of information—changes our judgment of the character from criminal to victim to enigma. Structure is the delivery system for empathy and judgment.

Movement and Velocity

Structure controls the velocity of the narrative. It dictates the “metabolism” of the book. Short, clipped chapters with frequent breaks can accelerate our reading speed, creating a sense of urgency or fragmentation. Long, dense, unbroken chapters force us to slow down, creating a sense of claustrophobia or immersion.

How Readers Engage With the Progression of a Story

A story is a machine designed to move forward, but the engine of that movement is the reader’s mind. Our engagement isn’t static; it shifts constantly as we traverse chapters and scenes. The experience of following a narrative arc is defined by a cognitive loop of three primary forces: Anticipation, Delay, and Return.

Anticipation: The Forward Lean

Anticipation is the promise that something is coming. It is the structural hook that keeps the reader leaning forward. This doesn’t always mean a cliffhanger or a mystery. In a literary novel, anticipation might be emotional; for example, we anticipate a confrontation between two characters who have been avoiding each other.

Structure creates anticipation by opening “loops.” The author introduces a question or a tension and refuses to close it immediately. We read to bridge the gap between what we know and what we suspect.

Delay: The Art of Withholding

If anticipation is the promise, delay is the pleasure (and frustration) of withholding it. Narrative structure often uses digressions, subplots, flashbacks, or shifts in perspective to stretch out the tension.

Novice readers often view these structural delays as “fillers.” However, a sophisticated reader understands that delay is essential for emotional impact. If a tension is resolved too quickly, it holds no structural significance; the structure must make us wait for the resolution so that the release feels earned. The “middle” of a book is essentially a structural architecture of delay.

Return: The Satisfaction of Closure

This is the satisfaction of circling back. Great structures often spiral backward by returning to earlier motifs, settings, or questions with new information.

When a story ends by returning to where it began, it lets the reader measure the change. We see the same setting, but because of the structural journey we have taken, it looks different. The “Return” validates the reader’s attention by confirming that the details we noticed earlier were important.

This engagement relies heavily on inference. We are constantly guessing where the arc is bending. When a structure surprises us, it is because it successfully subverted the inference pattern it had previously taught us to follow.

How Sentences Contribute to the Sense of Narrative Movement

We often think of structure as “large scale”—chapters, acts, and volumes. But narrative structure is fractal; it repeats the same patterns down to the smallest unit: the sentence. The local phrasing and rhythm of the line are what carry the story’s actual momentum.

By way of analogy: if the plot is the map, the sentences are the terrain. You can have a “fast” plot that feels slow to read, for example. That is because the sentence structure is dense and rocky.

The Physics of Sentence Length

Consider the structural impact of sentence length.

- The long sentence: A long, labyrinthine sentence with multiple clauses forces the reader to suspend closure. It creates a feeling of complexity, anxiety, or interconnectedness. The reader must hold the beginning of the thought in their working memory until they reach the period. This creates a specific “structural texture” of mental effort—it feels like a deep breath.

- The short sentence: Conversely, a series of short, subject-verb-object sentences creates a staccato rhythm. It implies speed, clarity, or blunt impact. It offers frequent closure, letting the reader digest information in rapid succession.

Transitions and Continuity

Structure also lives in the white spaces between sentences. How does one thought move to the next?

- Associative structure: Some narratives move by association. For example, one word triggers a memory, which triggers a sensation. This mimics the structure of the human mind.

- Logical structure: Other narratives move by cause and effect—”Because he did this, she did that.” This mimics the structure of an argument or a history.

When we analyze the “voice” of a novel, we are often just analyzing its micro-structure: how the lines carry momentum, restraint, or stillness.

The Broader Concepts Behind How Stories Are Understood

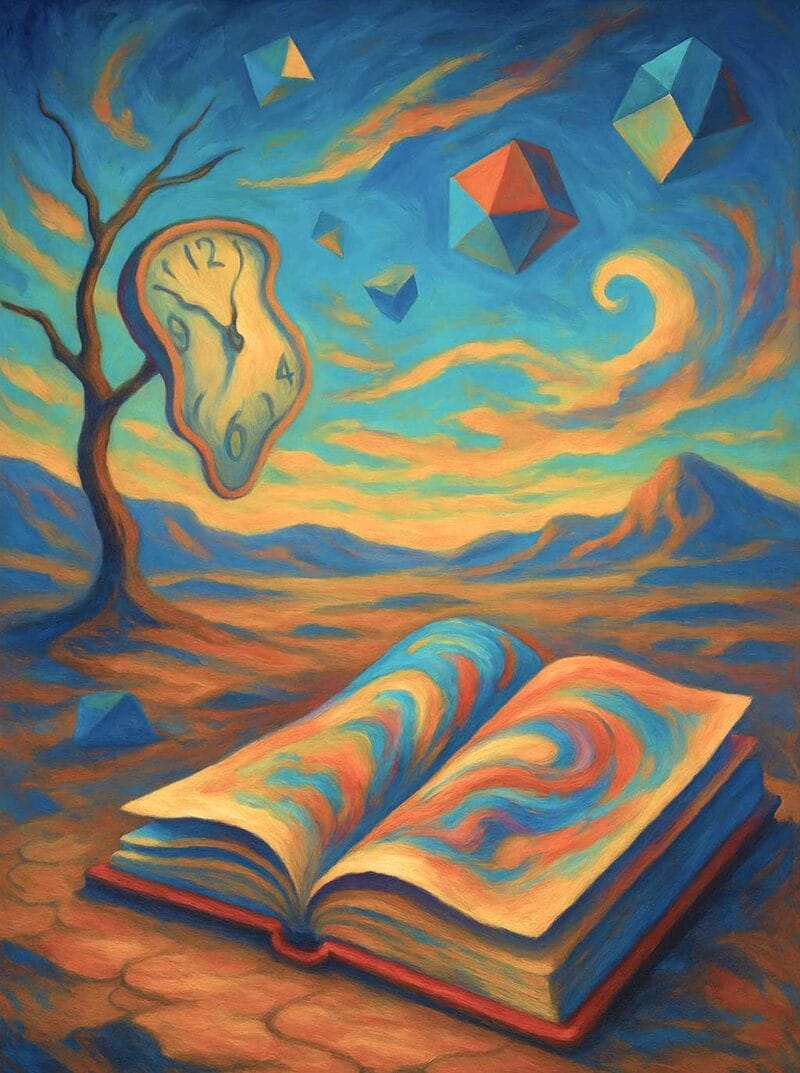

Beneath the visible text (the sentences and chapters) lies the conceptual framework that holds the story together. These are the abstract layers—Time, Perspective, Memory, and Distance—that guide the reader’s sense of what is being revealed or withheld.

Time as a Conceptual Basis

Narrative time is elastic. It is rarely 1:1 with real time.

- Compression: A structure might compress ten years into a single paragraph summary.

- Expansion: It might then expand five minutes into fifty pages of scene.This expansion and contraction is the primary way a narrative signals value. The structure tells us: “Those ten years didn’t matter, but these five minutes change everything.”

Perspective and Distance

Who is telling the story, and from where? This is a structural decision and not just a character decision.

- Retrospective distance: A narrator looking back from twenty years in the future has a specific structural power: they know the ending. This makes possible the techniques of foreshadowing and irony (“If I had known then…”).

- Immediate presence: A narrator speaking from the “now” (present tense) lacks that structural knowledge—they are trapped in the uncertainty of the moment. The structure of the story becomes more chaotic and reactive. The “distance” determines the authority and the “truth” of the narrative.

Memory as a Structural Element

In many modern narratives, structure mimics the operation of memory. Instead of a linear path, the story might loop, fragment, or blur. With this concept, memory is associative, nonlinear, and prone to distortion. When a book’s structure is fragmented, it is often asking the reader to piece together the truth, much like we piece together our own pasts. The structure itself becomes a puzzle within the story.

These conceptual layers are what makes a narrative structure hold its themes and tension together. Aside from having the structure as the container for the theme; these layers make the structure itself as the theme. For instance, when reading a fragmented book, you often read about a fragmented life.

How Narrative Structure Extends Beyond Traditional Fiction

The principles of narrative structure are not limited to the novel. They expand into memoir, hybrid books, documentary writing, and even the digital formats we consume daily. However, the reader’s expectations must adjust across these media.

Structure in Memoir and Creative Nonfiction

In fiction, the author invents events to fit the structural arc. In creative nonfiction such as memoir, the author is constrained by the truth. The “structure” of a memoir, therefore, is an act of curation and sense-making. The memoirist looks at the chaos of their real life and applies a narrative frame to it. They choose where to begin and where to end, which memories to highlight and which to omit.

When reading memoir, we should look at structure as an argument: Why did the author choose to tell this part of their life in this specific order?

Hybrid and Experimental Forms

In hybrid works (books that blend essay, poetry, and image), structure often abandons the “arc” entirely.

- The mosaic: A structure built of small, disparate tiles that form a picture only when viewed from a distance.

- The spiral: A structure that circles a central theme without ever directly answering it. Here, the reader attends to the accumulation of resonance instead of plot progression. They look for patterns rather than causes and effects.

Digital Narratives

Even in digital formats, we engage with structure. The infinite scroll, the hyperlink, and the blog post change how we perceive sequence and closure. Digital structure is often “modular” because it directs the reader to enter and exit at any point, in essence disrupting the traditional “beginning, middle, and end” authority of the book.

How to Read With Attention to Structure

We have discussed the theory, but how do we move from understanding these concepts to noticing them while we read? It requires a shift in attention—we must learn to read with a “structural eye”. However, this doesn’t imply that we need to analyze a book to death instead of enjoy it. It just means keeping key questions in the back of our mind that illuminate how we perceive movement, emphasis, and sequence in the story we read.

The Structural Reader’s Checklist

Developing a “structural eye” does not ruin the magic of reading but deepens it instead. To begin reading with attention to structure, ask yourself these questions as you turn the page:

The Question of Arrangement

- Ask: “Why did the author break the chapter here?”

- Look for: Chapter breaks that interrupt a moment of high tension vs. breaks that offer a natural pause. Notice what the break forces you to dwell on.

The Question of Speed

- Ask: “The story feels faster now. Why?”

- Look for: A shift in sentence length (shorter sentences), a shift in scene length (shorter scenes), or a reduction in interior monologue. Identifying the gear shift helps you appreciate the narrative pacing.

The Question of Sequence

- Ask: “We just jumped back in time. What do I know now that changes how I view the previous scene?”

- Look for: The juxtaposition of scenes. If a scene of a happy wedding is immediately followed by a scene of a funeral from ten years later, the structure is creating a commentary on the fleeting nature of joy.

The Question of Perspective

- Ask: “Who is seeing this, and what are they missing?”

- Look for: The limitations of the narrator. How does the chosen perspective restrict the information available to you?

The Question of the Beginning

- Ask: “Why start here?”

- Look for: The “inciting incident.” Does the book start in medias res (in the middle of action) to grab you, or does it start with a slow philosophical reflection to set a mood? The opening is the structural contract between author and reader.

These questions illuminate the movement, emphasis, and resonance of the work. Connecting these structural observations to your emotional reaction is the ultimate goal. By asking these questions, you’ll be able to transition from a passive consumer of story to active participants in the narrative experience.

Further Reading

Naming the Dog: The Art of Narrative Structure by Christie Aschwanden, The Open Notebook

Puzzling Through Story Structure by Karen Given, Narrative Beat

The Structure of a Story by fs.blog

The greatest chart on narrative structure that you’ll probably see today, but who really knows? on Reddit