There are moments in literature when a sentence starts to form and then halts. The halt does not arise from a lack of words; it stems from an awareness that continuation reaches an unsafe or impossible threshold. This is aposiopesis, a rhetorical figure in which a thought breaks off midstream with its completion left to inference.

The term derives from the Greek for “becoming silent.” The silence functions as an act of control, and its significance emerges through precision in what has been withheld. Writers employ it to signal emotional strain, restraint, or the point at which language no longer carries the full pressure of thought.

What Makes Aposiopesis Distinct

Aposiopesis is not simply marked by unfinished sentence—it requires a purposeful break. A speaker begins a thought, only to abandon it at the point where feeling peaks or expression falters. The break here is no casual pause or a decorative ellipsis. It is a rhetorical gesture that redefines expression through calculated silence. Completion falls away, and attention moves toward the gap that holds the unresolved element.

The interruption is deliberate, not the grammatical derailment one finds in anacoluthon, where language syntax veers off into a new or mismatched construction. Where aposiopesis falls away into silence, anacoluthon diverts into a fresh structure, breaking the syntax rather than simply cutting it short. For a fuller discussion of that device, see the article on anacoluthon.

The Burden of Interruption

Writers often rely on aposiopesis when a sentence cannot extend further without altering the balance between thought and voice. The technique may accompany suppressed anger, sorrow that defies simplification, or a recognition that articulating more would reveal too much. Though it may appear vague, it heightens concentration. The silence pulls focus toward what remains withheld.

In fiction, aposiopesis proves especially potent in dialogue and interior monologue, where syntax becomes an extension of voice. These interruptions halt expression with intention and establish the point at which language draws back. When crafted with care, the break introduces control, closing the sentence at the exact instant before disclosure.

Examples from Literature

Dickinson’s Final Silence

In the final lines of Emily Dickinson’s “I heard a Fly buzz—when I died—” (1863), the speaker’s voice abruptly ceases at a dash, coinciding with the moment of death:

And then the Windows failed – and then

I could not see to see –

The last line ends with an em-dash (“I could not see to see –”), indicating the poem’s thought is cut off at the instant the speaker dies. No further clause or continuation follows the dash. This is a classic example of aposiopesis: the syntax simply terminates, forcing readers to feel the sudden silence.

The break is not a shift to a new idea but a complete halt, suggesting the speaker’s final thought trails into wordless void. The dash conveys that death has literally stopped the sentence mid-flow, with nothing more said.

Austen’s Measured Silence

A quieter but equally deliberate instance of aposiopesis appears in Sense and Sensibility (1811), where Jane Austen employs the device not to convey rage or grief, but to register emotional restraint. In a conversation that hinges on what must remain unspoken, Elinor finds herself unable—or unwilling—to continue her sentence.

“You forget,” said Elinor gently, “that its situation is not … that it is not in the neighbourhood of …”

Elinor’s repetition and the dual ellipses suggest a deliberate decision to avoid naming a place laden with implication. The thought is abandoned mid-course, less from uncertainty than from the need to preserve composure. In this case, aposiopesis protects the dignity of the speaker and shields the listener from an unnecessary reminder.

The effect is subtle, but pointed. The silence that interrupts Elinor’s thought reveals a refusal to state something both parties already know. It is a tactful evasion, but not without meaning. Austen uses the break to contain feeling rather than dramatize it. The withheld location becomes more vivid for its absence, and the conversation acquires gravity through what remains unsaid.

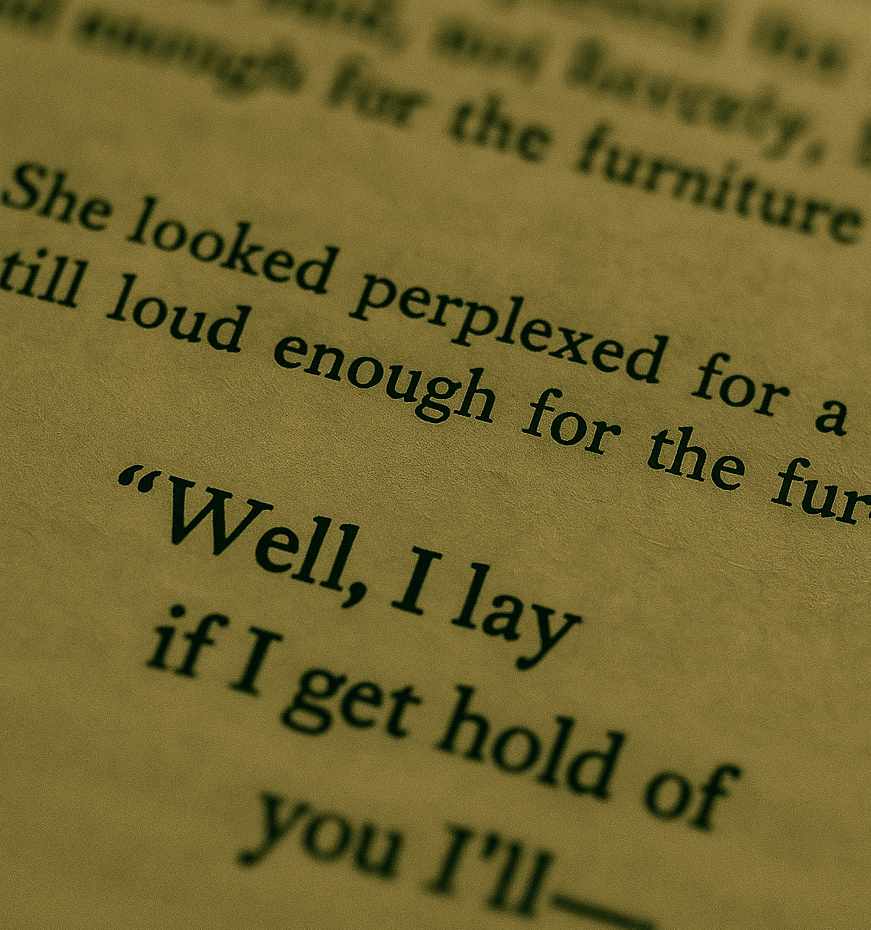

Twain’s Silenced Scolding

In The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876), Mark Twain offers a comic but precise example of aposiopesis, using it to convey frustration that tips from verbal threat into physical action. The sentence halts from clarity rather than confusion, ending where language gives way to gesture.

She looked perplexed for a moment, and then said, not fiercely, but still loud enough for the furniture to hear: “Well, I lay if I get hold of you I’ll—”

The sentence ends in a dash, the threat left unfinished. The speaker, exasperated but still composed, abandons the reprimand before naming its consequence. The aposiopesis marks a pivot from speech to implied action. Twain gives no resolution to the sentence because the woman’s intent is already clear; the tension lies less in what she will say next than in what she might do.

The device here does not carry the emotional gravity found in Lear’s disintegration or Elinor’s restraint, but it serves the same structural function: the interruption draws attention to the precise moment when continuing would undermine the speaker’s purpose. The humor lies in the theatricality of what is withheld. Twain uses aposiopesis to show that the act of stopping can communicate more than the act of saying.

Grammar, Yes—but Not Quite

While aposiopesis often appears with dashes or ellipses, punctuation does not define it. It is a syntactic rupture, not a visual cue. The interruption must serve meaning. A dash that merely peters out for stylistic flair does not suffice. What matters is the logic of the break. Does the sentence stop because something deeper, darker, or more dangerous wants to be said—but can’t?

It also differs from the sort of ambiguity or vagueness that avoids commitment. Aposiopesis implies specificity. It suggests that the thought could be completed—but isn’t. The choice not to say it becomes its own kind of clarity. Aposiopesis works by breaking the flow of prose and compelling it to crack.

In interior monologue, this may indicate psychological hesitation or the edge of a thought the speaker refuses to confront. In speech, it may dramatize conflict, concealment, or the emotional limits of dialogue. The sentence remains unfinished because it has succeeded in reaching the edge of what language will permit, not because it has failed.

Further Reading

Aposiopesis on Wikipedia

New Writers Often Make These Glaring Mistakes by Malky McEwan, pen2profit.substack.com

What is APOSIOPESIS? Definition & examples using William Shakespeare by Dr Octavia Cox, YouTube