James McBride’s The Good Lord Bird (2013) is a bold and inventive take on one of the most volatile periods in American history. Winner of the National Book Award for Fiction, the book reimagines the story of John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry through the eyes of Henry “Onion” Shackleford, a young enslaved boy who is mistaken for a girl and becomes entangled in Brown’s crusade.

McBride, known for his sharp wit and ability to merge humor with serious historical themes, crafts a story that is both irreverent and deeply moving. Rather than presenting a straightforward historical account, the book uses satire, irony, and historical revision to paint a richly drawn protagonist while examining political and racial tensions of mid-19th-century America.

Historical Context and Setting

The book unfolds against the backdrop of the antebellum United States, a time when tensions over slavery were reaching a breaking point. The events in the book unfold in the late 1850s, a period marked by fierce sectional conflict over slavery. Brown’s 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry was a pivotal moment leading up to the Civil War.

McBride’s depiction of pre-Civil War America is not merely a static background. It is animated by contradictions: a country simultaneously preparing for emancipation and clinging to bondage. The book moves through towns and camps riddled with suspicion, betrayal, and makeshift alliances, all grounded in the tension between moral certitude and political chaos.

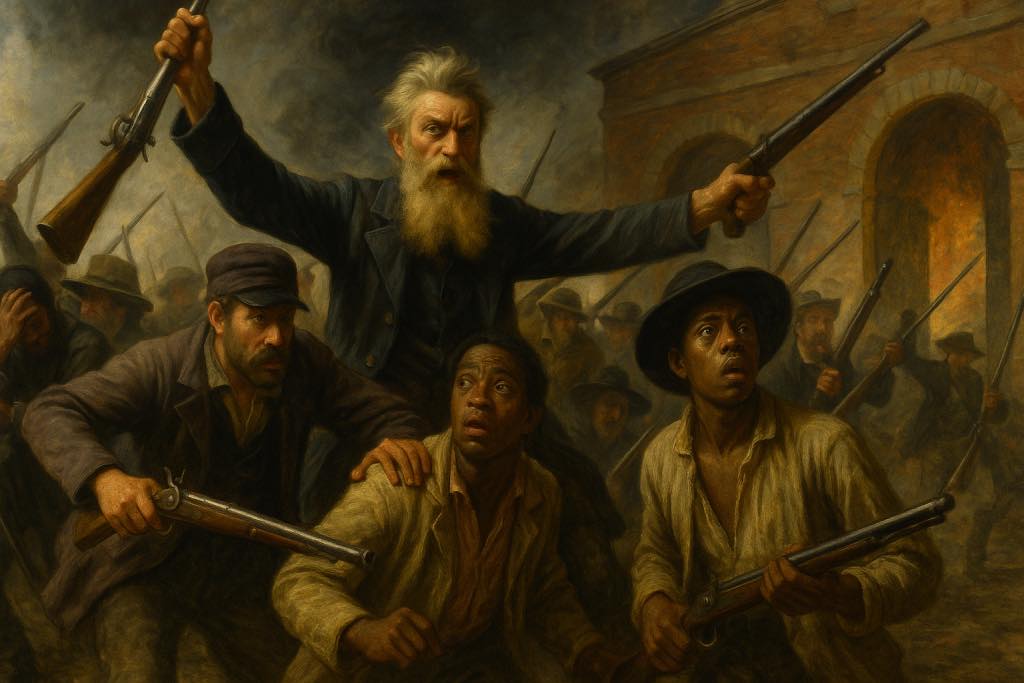

McBride constructs a vivid world where Kansas Territory seethes with bloodshed and uncertainty. Known as “Bleeding Kansas,” this battleground foreshadowed the national conflict that soon followed. A radical abolitionist, Brown believed armed insurrection was the only way to overthrow slavery. His attack failed, but his execution turned him into a martyr for the abolitionist cause.

Plot Summary and Narrative Voice

The story is told through the voice of Henry, the young enslaved boy in Kansas, who is freed (or perhaps kidnapped) by Brown after a violent skirmish. Brown, convinced he has rescued a young girl, takes Henry, whom he nicknames “Onion,” under his care. Rather than correct the mistake, Henry chooses to maintain the deception, believing it will afford him greater protection.

This central conceit gives rise to a series of misadventures that carry Onion from Missouri to Virginia, culminating in the infamous raid on Harpers Ferry. The choice of a first-person perspective, especially through a child masking his identity, adds tension and irony. Onion does not idolize Brown; his account offers skepticism, humor, and, at times, bewilderment. McBride plays with the idea of unreliable narration, letting Onion’s misunderstandings, evasions, and accidental truths define the world he sees.

The titular “good lord bird,” an ivory-billed woodpecker, serves as a recurring symbol. Brown believes the bird is a sign of divine providence, while Onion sees it as a harbinger of chaos. The bird’s elusive nature mirrors the book’s central question: Is freedom a matter of destiny, or is it something one must seize despite the risks?

Themes Explored in the Book

Beneath the adventurous surface and comedic tone, the book explores profound themes. For one, the search for identity is central to Onion’s journey. Another is freedom, which is examined in its many forms: physical liberation from bondage, the freedom to define oneself, and the spiritual freedom that Brown so ardently pursues, albeit through violent means. The book also scrutinizes the nature of faith and fanaticism, particularly through Brown’s character.

Gender and Identity

Onion’s cross-dressing, initially imposed by circumstance, compels him to confront gender in ways he never anticipated. As a Black child passing as a girl, he witnesses both the privileges and dangers of being perceived differently. The decision of Onion to maintain his disguise as a girl is not a trivial plot twist but a recurring source of tension and reflection throughout the book.

Onion’s performance becomes a way of negotiating power in spaces where children, particularly enslaved ones, are given little control over their fate. The disguise allows McBride to explore the absurdities and contradictions in gender roles of the period. Onion’s observations, sometimes crude but often ironic, reveal how little control he has over the body that others perceive.

Satire on Race and Freedom

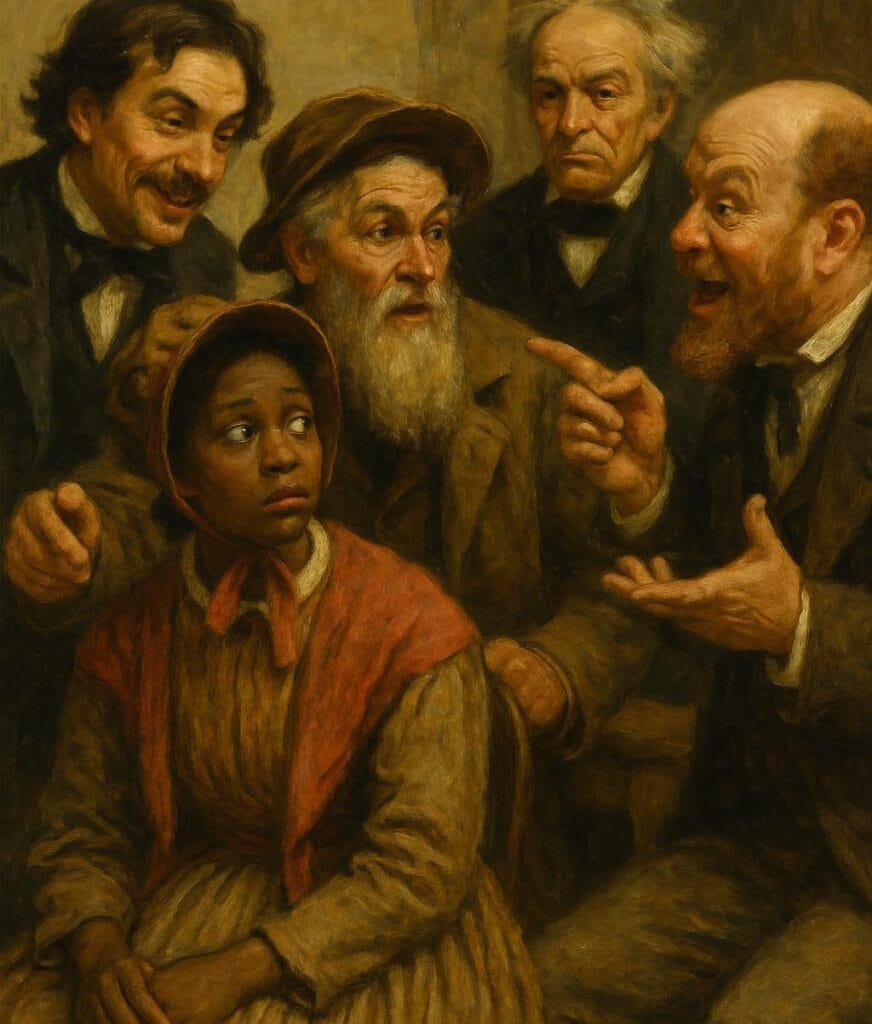

Satire in The Good Lord Bird is not incidental. McBride uses it as a scalpel to dissect the racial hypocrisies of the United States. Onion is placed in situations that expose the absurdity of racial hierarchies, where white men deliver fiery sermons about equality while owning human beings, or where celebrated leaders like Frederick Douglass appear more concerned with reputation than rebellion.

McBride’s distinctive tone engages with profound subjects without slipping into solemnity. He exposes the contradictions in American notions of liberty, revealing how high ideals erode under pressure or self-interest. Onion’s journey is not a straightforward quest for liberation. At times, he refuses Brown’s mission, choosing survival over martyrdom. This tension between the ideal of freedom and its grim reality becomes the novel’s enduring power.

Faith and Morality

Brown’s fanaticism blurs the line between righteousness and madness. His character is driven by an unshakable belief in divine justice; he views himself as an instrument of God, yet his actions often lead to unnecessary bloodshed. Through Onion’s amused, skeptical lens, Brown’s religious devotion borders on the unhinged. However, McBride avoids reducing Brown to a merely deranged figure. The book poses a serious question: Can moral rightness justify extreme actions?

While Brown’s methods are brutal and often ineffectual, McBride acknowledges the depth of his commitment to the abolitionist cause, even as he prompts readers to grapple with its terrible cost. The book does not offer easy answers about whether his violence was justified, instead presenting morality as a shifting and ambiguous concept.

Character Analysis

Henry “Onion” Shackleford

Onion is painted as neither a traditional hero nor a passive observer. He is an unreliable yet deeply engaging narrator. Through his wit, survival instinct, and confusion, the narrative places him at the center of the book’s many contradictions. His youth and naivety color his perspective, making his account of historical figures like Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman both humorous and revealing.

The book’s most compelling character arc is Onion’s growth from a boy who merely wants to stay alive to someone who begins to understand the cost of freedom. He does not understand everything he witnesses, does not undergo a dramatic transformation, nor is he a moral beacon. Instead, his reflections shift subtly over time.

John Brown

McBride’s portrayal of Brown avoids romanticism; he is portrayed as both heroic and delusional. He is stubborn, often reckless, and oblivious to nuance, with his unwavering belief in his divine mission making him a fascinating, contradictory figure. Onion’s alternating awe and exasperation mirror the complexity of Brown himself.

McBride neither glorifies nor vilifies Brown, instead presenting him as a man whose convictions outpace his judgment. By refusing to make Brown purely villain or hero, McBride presents the consequences of conviction in times when moderation often served as a cover for inaction.

Supporting Characters

From the fiery abolitionist Harriet Tubman to the opportunistic Frederick Douglass, the book populates its world with historical figures reimagined through Onion’s eyes. These portrayals are often exaggerated for satirical effect, yet they reveal deeper truths about how legends are constructed.

Other supporting characters, such as Pie (a prostitute who briefly shelters Onion) and various members of Brown’s militia, serve as foils or counterpoints to the central figures. Douglass, often revered in American history, appears calculating and concerned with his image. Pie represents a form of power and protection that stands in contrast to Brown’s fire-and-brimstone rebellion.

Writing Style, Tone, and Structure

McBride’s prose is vibrant and rhythmic, which echoes 19th-century vernacular without slipping into antiquated stiffness. The language moves with a musical cadence that reinforces Onion’s storytelling instincts: digressive, anecdotal, and rooted in the folk tradition. McBride constructs the tone through an irreverent lens, even when the subject matter turns grim. This tension between tone and content steers the narrative clear of heavy-handed solemnity or flippant satire.

The book’s structure mirrors the turbulence of Onion’s journey. The episodic, picaresque structure suits Onion’s transient existence, moving him through loosely connected yet thematically rich encounters. Though fragmented, the story coheres through Onion’s distinctive voice and the looming presence of Brown, whose fanaticism anchors the chaos.

Humor functions as more than a stylistic device. It is structural and woven into the fabric of the story to expose the absurdities of a fractured society built on violent contradictions. Onion’s naïve yet piercing observations satirize abolitionist zealotry, pro-slavery rhetoric, and the hypocrisies of the antebellum South. The comedy never diminishes the horror of slavery; instead, it sharpens the critique, making the injustices starker.

Miniseries Adaptation

The Good Lord Bird was adapted into a 2020 Showtime miniseries to bring McBride’s darkly comic vision to a broader audience. The adaptation, starring Ethan Hawke as John Brown and Joshua Caleb Johnson as Henry, undertook the considerable challenge of capturing the book’s unique blend of boisterous humor and historical gravitas, an inherently complex feat when moving from the internal world of prose to the externalized presentation of a visual medium.

Hawke’s frenetic, larger-than-life portrayal of Brown captures the character’s messianic fervor, while Joshua Caleb Johnson’s Henry “Onion” Shackleford retains the wry, observational humor that defines the book’s narration. However, the series leans more heavily into visual spectacle, particularly in its chaotic battle sequences, which, while gripping, slightly dilutes the book’s reliance on Onion’s internal perspective and linguistic flair.

The miniseries grapples with the same central tension as the book: the absurdity of history when viewed through the eyes of an unwilling participant. The adaptation may lack some of the book’s literary ingenuity, but it amplifies the story’s visceral impact, ensuring McBride’s blend of history and satire reaches viewers who might never encounter the original text. The series compensates by heightening the contrast between Brown’s grandiose rhetoric and the messy reality of his crusade, using cinematography and performance to underscore the same themes of delusion and sacrifice.

Onion’s unreliable narration, the digressive structure, and the constant tonal shifts between absurdity and terror are deeply literary techniques that rely on the flexibility of the written word. The adaptation leaned into drama and moral conflict, which made the story more accessible to a general audience but altered its rhythm and mode of commentary. Scenes that unfolded through Onion’s naïve yet perceptive misreadings in the book became more literal onscreen, losing some of the ambiguity that McBride had carefully constructed through language and voice.

Despite these differences, the adaptation played a role in extending the reach of McBride’s work, introducing the story to viewers who may not have encountered it in print. Ultimately, the miniseries reinforces the book’s cultural resonance while inevitably altering its interpretive lens. Both versions, however, succeed in reframing Brown’s legacy not as a tidy historical footnote but as a chaotic, morally ambiguous struggle.

Selected Passage with Analysis

That flummoxed me right there. She knowed I was a boy. But I was an inside nigger. Privileged. The men in Miss Abby’s liked me. Pie was my mother, practically. She had the run of things. I didn’t need to bother with no mealymouth, lowlife, no-count, starving pen nigger who nobody wouldn’t pay no attention to. I had sauce, and wouldn’t stand nobody but Pie or a white person sassing me like that. That colored woman just cut me off without a wink. I couldn’t stand it.

Pages 150-151, The Good Lord Bird by James McBride

In this passage, Onion reflects on his elevated status within a brothel, highlighting how his mistaken identity as a girl — and his connection to Pie — grants him a position of relative privilege. Onion recognizes the sharp contrast between his situation and that of a field worker, whom he derides as “no-count” and “starving.” This comparison reveals how rigid social hierarchies existed even among enslaved or marginalized people, where access to resources or proximity to authority created sharp divisions.

Onion’s resentment stems not only from being insulted but from being treated as if he were ordinary. His pride in being an “inside nigger” and his willingness to accept correction only from Pie or white patrons expose how power operates in layered, often contradictory ways. Although Onion is powerless within the larger racial hierarchy, he clings to his limited status, internalizing the system’s values and replicating them in how he treats others.

McBride uses this passage to show how Onion has absorbed a stratified worldview, one defined by survival and performance rather than principle. The scene illustrates how identity is not just imposed from above but also formed through horizontal competition, envy, and self-preservation.

Further Reading

On James McBride’s THE GOOD LORD BIRD by Elizabeth Bastos, Book Riot

‘The Good Lord Bird’ is a twisted take on an abolitionist’s story by Hector Tobar, Los Angeles Times

National Book Awards leave winner lost for words by John Dugdale, The Guardian

What’s Fact and What’s Fiction in The Good Lord Bird by Rebecca Onion, Slate