Explore This Topic

- Texture as Element of Prose Style: How Language Feels

- Density of Language: The Weight of Words in Textured Prose

- Omission in Prose: What Writers Leave Out Between Words

- Speed of Language: How Sentences Control Pacing in Prose

- Musicality in Prose: Rhythm and Sound of Textured Language

- Gravity of Language: When Sentences Carry Consequence

- Surface of Textured Prose: The Grain of Language

My Reading Note

After years of reading, I began to notice that prose has a texture. Some novels are written densely, others sparely. Some move quickly, others slowly. Over time, I started tracking these qualities across different books and authors. This article presents the observations I made.

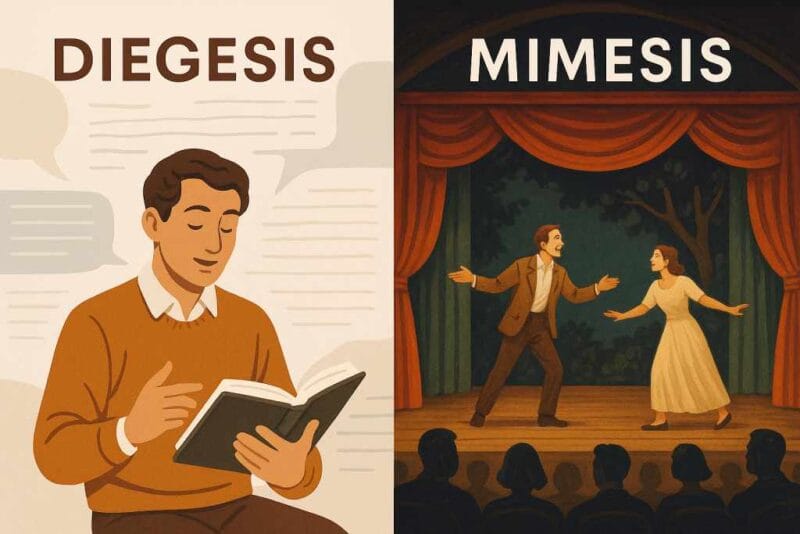

Prose style is built from foundational elements: diction, syntax, voice, tone, and figurative language. These are the tools writers use and the terms critics reach for when discussing how a text is constructed. But they describe what goes into prose, not how it feels to move through it.

When finishing a book, it leaves more than its story behind. It also leaves an impression of how it felt to read it: dense or airy, fast or slow, heavy or light. These sensations arise from specific choices in sentence construction and paragraph arrangement. They exist independently of plot, character, or theme.

Most literary readers already sense texture but lack a vocabulary for describing it. Over time, certain qualities surface repeatedly in the passages that stay with readers: density, omission, speed, musicality, gravity, and surface. This article is organized around those six dimensions. They are not alternatives to diction or syntax, however. They are what those fundamental elements produce when they work together.

I started with plot like everyone else. It took me years to realize that how a sentence feels matters as much as what it says. After enough reading, I came to recognize that what I was feeling is called texture.

What is Texture in Prose?

Texture in prose refers to the sensory qualities generated by language on the page. It concerns how a sentence feels to move through rather than what it means. Readers encounter texture in the accumulation of words, the structure of sentences, the spacing of paragraphs. These features combine to create an experience that is partly aural, partly physical, or even temporal.

Several dimensions contribute to this kind of experience:

- Density concerns how much content is packed into a given space. A dense passage loads meaning into every phrase; a sparse one leaves room to breathe.

- Omission refers to what the writer leaves out. What is withheld becomes present in its absence. Paragraph breaks, skipped years, and unfinished sentences give the reader room to fill the gaps.

- Speed governs the pace at which a reader moves through a passage. Short sentences and active verbs accelerate; long clauses and interruptions slow things down.

- Musicality encompasses rhythm, cadence, repetition, and sound. Some prose calls attention to how it sounds; other prose is more neutral, letting meaning pass through without drawing attention to itself.

- Gravity describes the sense of consequence that sentences carry. Some feel substantial, as if each word matters. Others feel slight, even when the subject is not.

- Surface captures the grain of the writing. Smooth prose glides; rough prose catches and calls attention to itself, making the reader slow down.

I first felt texture before I knew what to call it. Reading Faulkner made my chest tight, and reading Hemingway made the page feel empty. I did not have words for these sensations at the time.

A dense passage may also move slowly. A sparse one may move fast. Writers orchestrate them in combination, and readers learn to notice how. These dimensions work together, summarized as follows:

| Dimension | Spectrum | What It Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Density | Dense ←→ Sparse | How much content per space |

| Omission | Present ←→ Absent | What is left out or withheld |

| Speed | Fast ←→ Slow | How quickly the reader moves |

| Musicality | Rhythmic ←→ Plain | Sound patterning |

| Gravity | Heavy ←→ Light | Sense of consequence or weight |

| Surface | Smooth ←→ Rough | Texture at the word level |

Reading for Texture

Knowing the dimensions of texture is one thing, but noticing them while reading is another. Most readers absorb texture without attending to it; the prose feels dense or spare, fast or slow, but the reader does not stop to ask why. This section offers a method for reading with more awareness.

I still miss things on every reread, and each pass shows me something I did not notice before. That is not failure on my part but simply what texture does. If you are unsure where to start, begin with a single dimension. Notice it in the next book you read, then come back for another.

The method has four steps:

- Notice what you feel. Pause when a passage affects you. Ask yourself what you are feeling. Is the prose dense? Is it moving quickly? Does it feel heavy or light? The goal is not to analyze yet, only to register the sensation.

- Locate the source. Once you have named the feeling, look for what produces it. If the prose feels dense, look at the sentences. Are they packed with imagery? Do they carry multiple ideas? If the prose feels fast, look at sentence length. Are the sentences short? Are the verbs active? If something feels omitted, look for what is not there. What has the writer left out?

- Name the dimension. Match what you find to the vocabulary from the previous section. Density. Omission. Speed. Musicality. Gravity. Surface. Using the terms gives you a precise way to describe what you noticed.

- Ask what it does. Texture carries meaning. A dense passage may create a sense of overwhelm, or a fast passage may generate urgency. An omission may implicate the reader in filling the gap. Once you have identified the dimension, consider what it contributes to the passage as a whole.

This method takes practice. At first it will slow your reading considerably. With time, noticing texture becomes more automatic, and the slowing happens only when you want it to.

Texture in Context

The preceding sections introduced the dimensions of texture and a method for reading them. This section shows how those dimensions appear in the work of writers who made texture central to their meaning. The examples that follow are brief; each will receive fuller treatment in a separate article.

Ernest Hemingway built his prose on omission. In his hands, what is left out matters as much as what remains. Sentences end before they resolve, and dialogue conceals more than it reveals. Readers must supply what the writer withheld. The result is a texture of absence, a prose defined by its silences.

Toni Morrison worked at the opposite end of the density spectrum. Her sentences accumulate meaning through layering, repetition, and a music that is unmistakably her own. Passages that appear simple on first reading reveal themselves as densely woven, carrying history and emotion in equal measure.

Virginia Woolf manipulated speed with precision. Her long sentences slow the reader and force attention onto the moment. Then a short sentence arrives, abrupt, and the pace shifts. The reader experiences time as her characters do: elastic, subjective, never uniform.

James Baldwin achieved gravity through restraint. His sentences carry consequence without strain. Even at their most passionate, they remain controlled. The reader registers what is being said without being told how to feel about it.

These writers are not anomalies. They are examples of what texture can do. The articles that follow in this series will examine each in greater depth, along with others who made the felt qualities of prose central to their work.

I did not set out to write about these particular writers. They are simply the ones I kept returning to when I stopped looking for the usual names. Your list would likely look different.

Writing Styles: Key Elements, Types, and Examples

These three articles from the archive offer useful background for the discussion here. The “Writing Styles” explainer introduces the basic vocabulary for talking about prose that covers terms like diction, syntax, and voice. “Tone vs. Mood” addresses a related distinction that readers often confuse with texture but functions differently: tone belongs to the author or narrator, mood to the reader. The essay on “Experiential Writing” examines how narrative structure builds consciousness on the page, which connects to texture’s concern with how prose feels to move through.

Further Reading

When Prose Is VERY Praiseworthy by Dave Astor on Literature

What are the best examples of richly textured prose? on Quora

What prose is so utterly beautiful that you had to stop, put the book down, and breathe? on Reddit