My Reading Note

I remember reading a history textbook telling one thing about the war, with my grandfather telling another. Both seemed to be true. That got me thinking about narrators in novels who we’re told to trust. What are they really telling us?

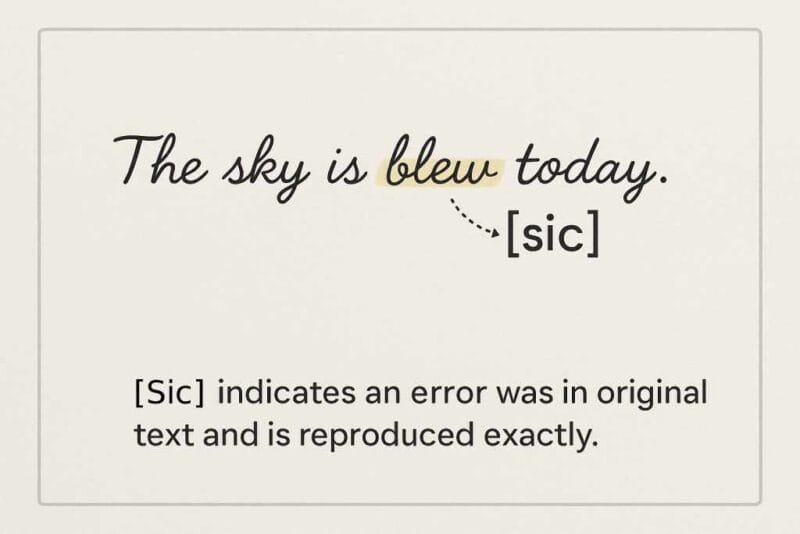

The “reliable narrator” is a provisional agreement, not a guarantee. In narrative theory, the term describes a storyteller whose account we are expected to accept. It forms a basic contract between the text and the reader: that the narrator will provide a credible version of the story’s world and events.

I find most definitions of the reliable narrator misleading. They treat it as a stable character trait when it is actually a provisional effect, constructed by the text and subject to the reader’s constant re-evaluation.

However, “reliability” is not an inherent trait of a narrator but a constructed effect. It is engineered through specific techniques that manage reader perception. To understand it, we need to examine the mechanisms of voice, perspective, and information control that create an impression of authority and trustworthiness.

The Engineered Effect of Reliability

A narrator’s perceived reliability is not an innate characteristic but a function defined by technical components. The primary mechanisms are narrative voice (who speaks) and focalization (who perceives). A third-person omniscient voice, claiming total knowledge, traditionally asserts maximum authority. A first-person narrator builds trust differently, through a consistent personal logic and the gradual corroboration of their testimony by other story elements.

This distinction is critical: a consistent narrative voice does not guarantee an objective account. It guarantees a coherent perspective. Reliability is often a judgment of coherence, not truth.

This engineered reliability serves a clear narrative purpose: it stabilizes the fictional world by influencing the reader to invest in its internal logic. The trusted narrator acts as a guide who directs attention and establishes normative judgments. The reader’s contract with the prose depends on this purpose.

To illustrate, a narrator can be meticulously consistent while being fundamentally wrong, a distinction crucial to novels with a narrator who is acting with self-deception while telling the story. Stevens in Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day (1989) is a famous example.

The Inherent Limits of the Contract

The contract of reliability carries inherent limitations. Each narrator works with a defined degree of focalization, a term for the scope of their knowledge and perception. A narrator with limited focalization cannot relay events beyond their awareness. Furthermore, all narration involves selection; the omission of detail distorts a narrative with the same effect as a false account.

A Contrarian View: The Naive and the Over-Aligned

The concept of a strictly reliable narrator contains a central paradox: such a voice can fail the narrative it serves. Consider the naive narrator, like the young Pip in Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations (1861). His account is faithful to his limited perception and meets a technical standard for reliability, yet it lacks the depth required for full interpretation. Conversely, a narrator whose perspective aligns too perfectly with a text’s implied judgment can feel didactic, reducing complexity. Authentic reliability frequently depends on a narrator’s demonstrated awareness of their own limits, rather than on flawless perception.

The Spectrum of Narrative Trust

The binary of “reliable” versus “unreliable” is a blunt instrument. A more precise analysis considers a spectrum defined by the narrative purpose of a narrator’s limitations. The central question shifts from “Can this narrator be trusted?” to “How does this narrator’s specific access to truth serve the story’s design?”

The following table contrasts three positions on this spectrum:

| Definition & Narrative Purpose | Reader’s Primary Task | Classic Example |

|---|---|---|

| Formally Reliable Narrator | ||

| A narrator whose rendering of facts, events, and norms the text presents as authoritative. Their limitations (if any) are not a central problem. | To comprehend the story world through the narrator’s authoritative perspective. | The omniscient narrator in George Eliot’s Middlemarch (1871). |

| Functionally Reliable Narrator | ||

| A narrator who provides a factually consistent account, but whose limitations are the narrative’s central subject. | To perceive the story in spite of the narrator’s limitations, which the text makes legible. | Stevens in Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day. |

| Unreliable Narrator | ||

| A narrator whose account is shown to be compromised, breaking the initial reader contract. | To reconstruct the story against the narrator’s account, correcting its gaps or distortions. | Tony Webster in Julian Barnes’s The Sense of an Ending (2011). |

This framework treats reliability as a rhetorical function rather than a character trait. The “functionally reliable” narrator is the most critical category, as it dissolves the simple opposition. In this mode, the narrator’s steadfast reliability does not conceal the truth but delivers the truth of their limitation with maximal effect. The reader’s work is not to distrust the narrator’s facts but to interpret the profound gap between those facts and their meaning.

This is where the common academic take falls short. Critics often treat the “functionally reliable” narrator as a subset of unreliability. I argue it’s the more sophisticated device: it uses the reader’s trust as the primary material for the tragedy.

Methodological Scope and a Foundational Model

The preceding analysis rests on a clear distinction: the narrator is a formal component of the text and not just a biographical proxy for the author. Hence, narrative voice is a technical device. Reliability, then, becomes an effect generated by this device, open to examination through its operational mechanics.

Observed Patterns in Reader Reliance

Reader trust is rarely absolute. It is a hypothesis constantly tested against new information. We extend provisional credit to a voice, waiting for internal contradictions or external validation. When a narrator’s account is seamlessly corroborated by other characters or events, our trust solidifies. When contradictions or new evidence appears, the contract requires renegotiation. This process of testing and adjustment defines the reader’s experience with a psychologically complex narrative.

Unreliable Narrator: The Active Reader’s Contract

These two articles from the archive examine the narrative voice. The first-person point of view is a mode defined by a subjective pact with the reader, a pact that can be straightforward or complicated. The unreliable narrator entry defines that complication. Reading them together provides the necessary context for a thorough analysis of narrative perspective.

Further Reading

The Myth of Reliable Narrators in Fiction by Chad Musick, The Musicks in Japan

Is there such a thing as a Reliable Narrator? on Reddit

Can a narrator be both unreliable and reliable in terms of facts? How would this be possible? by Quora