The expression “reading is living” is often repeated and treated as a familiar sentiment, assumed to reflect a general enthusiasm for books. A more rigorous claim, however, resides beneath this simplicity: it concerns the discipline and structure required to sustain a reading life, rather than mere escapism or emotional attachment.

To read consistently over time is to adopt a particular mode of life. It defines how time is divided, how attention is directed, and how internal rhythms are formed. Reading reorganizes daily routines; it does not simply supplement them. For those who read regularly, the distinction between reading and living becomes less clear. The two merge through habit and sustained practice; metaphor plays little role in this process.

This article examines how such a life is structured. It focuses on what happens when reading becomes a central activity—one that influences thought patterns, cognitive endurance, and the way time itself is experienced. The inquiry defines reading as a central, analytical activity and not just a source of comfort or a tool for self-improvement.

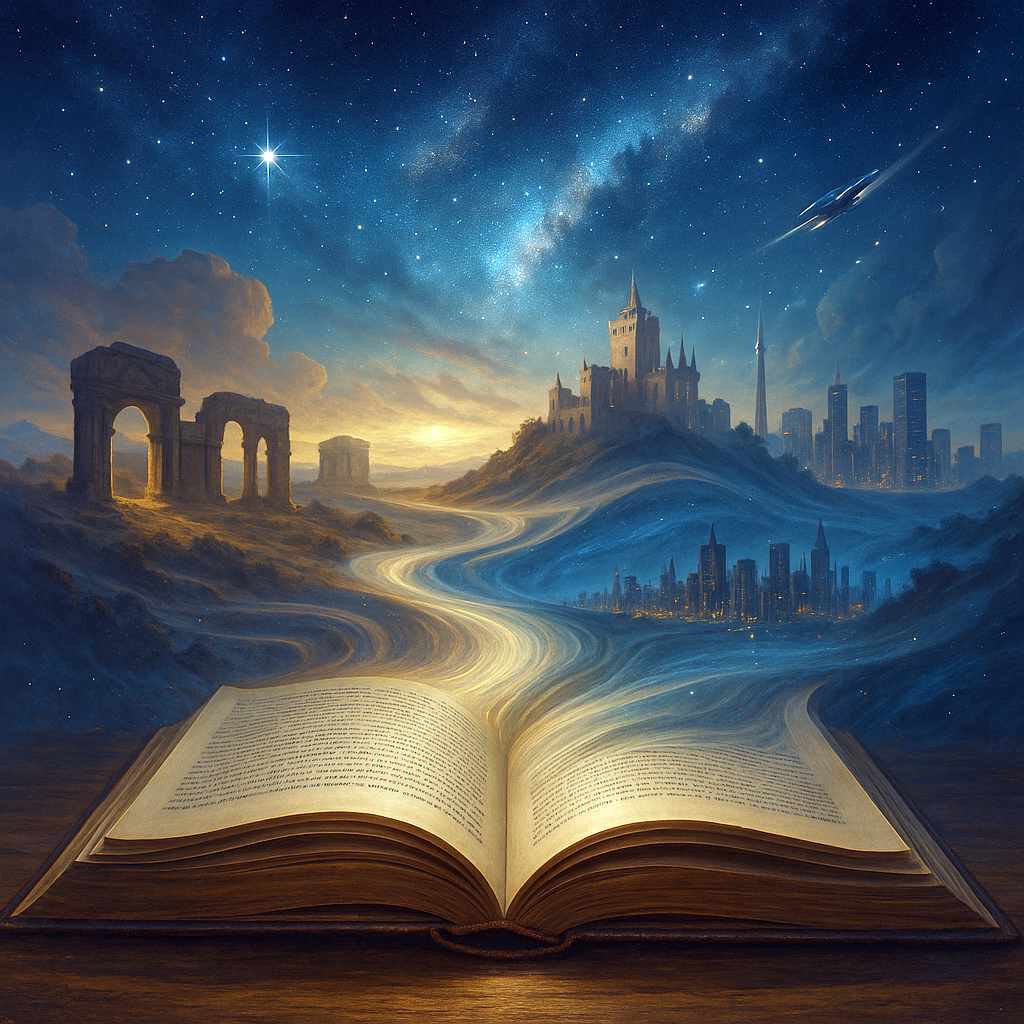

The Book as a Timescape

Reading alters the experience of time in ways that are difficult to notice at first. It does not simply fill the hours but reconfigures how they are perceived, drawing the reader into a different temporal framework.

Within a few pages, the present moment begins to loosen, and the reader moves between centuries, across continents, through imagined lives whose timelines progress according to their own internal logic. A novel begun with the morning light may encompass an entire generation by dusk, yet the reader remains anchored in the same location undisturbed.

Temporal Displacement and Cognitive Immersion

Psychological studies on reading have observed what is often called narrative transportation—a cognitive state in which attention becomes so focused on a story that the reader’s awareness of real-world time diminishes.

This is not exclusive to fiction. Even essays, historical writing, and biographies can produce the same effect when the material is absorbing enough. The mechanism is simple: as attention deepens, time awareness recedes, and the passing of time becomes secondary to the sequence of words.

Books operate on timelines that are independent of lived chronology. A single sentence can span decades, a chapter can dwell on one afternoon, or an entire work can extend across generations while taking only hours to read. Others unfold slowly, demanding patience and measured attention. While the body remains in one place, the mind travels across durations that would otherwise take years to experience.

Habitual Patterns and Seasonal Returns

With time, readers develop personal rhythms, habits that follow the patterns of light, season, and state of mind. Some prefer short fiction in the early morning, longer novels in the evening, or poetry during travels. These preferences are intentional; astute readers organize their time across the day by anchoring intervals to language on a page, rather than to obligations.

For some readers, certain authors serve as cyclical markers. The act of rereading their books is undertaken to recall that past emotional context and mental state, not simply to remember the plot. These readers often gauge the passage of years by the books they read during those times. Time, in this sense, is documented through sentences once read and remembered, etched onto memory as timescapes of the mind.

Reading as a Time Capsule

Books preserve a temporal structure that remains stable, no matter when or on what page they are opened. A novel written a century ago unfolds in the present tense for the reader, and its narrative voice does not age. The narrative pauses, cadences, and conclusions remain fixed until activated again. Each reading reanimates that structure, and the reader enters it not as a spectator but as a participant. The surrounding world may change, but the interior pace of the book holds steady.

To read, then, is not to pass time but to step into a defined temporal frame, one that often moves slower, encourages more careful thought, and rewards closely reviewing the text. The book becomes a capsule because it creates a space in which time behaves differently. For a few hours, the reader is not simply reading within time but according to a different one.

Memory, Recollection, and Books That Remember for You

Reading is not only a matter of absorbing what is on the page. A book, once read, does not simply pass through the mind but could stay lodged, partially and unevenly, but not passively. Years later, a sentence or a passage may surface again. Not necessarily the most important one, but the one encountered in a particular season, under a particular light, with a particular state of mind.

Readers do not preserve only the contents of what they’ve read. They often retain the setting and circumstances in which they read it. Where they sat or how they felt at that time. What was happening elsewhere. These details may never have been written down or marked on the page, yet a single line can pull an entire year into focus. This is how books can carry memories for the reader.

Rereading is Some Kind of Remembering

Rereading even makes this more evident. The actual words on the page may not change, but their meaning shifts. Something that once seemed peripheral now stands out. A passage once skimmed over now holds a special attention. The reader has not only changed, but so has the memory of having read it before. One reading experience layers over another.

A Private Library of Time

Personal libraries often reflect this. Not just as collections of titles, but as a form of record-keeping. Certain books remain unread but are kept nearby, while others are worn from repeated handling. Their place on the shelf may be fixed, but their meaning is not. They serve not only as references but as markers of who the reader was when they first reached for them.

In this way, memory begins to rely on reading, not for facts but for structure. It organizes time not through the sequence of hours, but through reading patterns. What was read, when, and how it stayed. A novel becomes less an object than a marker. Over time, the reading life forms its own archive, where books are not simply catalogued but actively recalled, often by a specific passage or phrase.

The Inner Continuity of Reading

Reading creates a mental pattern that continues even after the book is put away. It doesn’t function as a separate track from everyday life, nor does it take its place. Instead, it becomes part of how a person thinks and interprets what happens around them.

Over time, regular reading begins to affect habits of thought—how one notices details, how one responds to language, and how one processes experience. This influence is not dramatic or sudden. It builds gradually, as the tone and rhythm of what has been read fade into the background of thought and begin to sway how a person moves through the day.

How Reading Alters Perception

What reading builds is not a second life, but a persistent undercurrent—one that alters perception without drawing notice to itself. This occurs not due to the book’s voice being dramatic or profound, but because it assimilated so easily into the grain of the reader’s thinking.

The inner life cultivated by reading neither supersedes external experience nor exists in opposition to it. However, this interior sphere becomes incorporated into how an individual processes their days. A passage encountered weeks prior may subtly influence the wording of a conversational response or color the subsequent reflection on something observed or heard.

Phrases encountered in solitude begin to echo in real-world exchanges, altering how things are heard, interpreted, or answered. The influence is neither immediate nor theatrical; it is subtle, distributed, and difficult to isolate, yet it gradually becomes part of how a person thinks in the real world.

The Cognitive Demands of Reading

Reading takes many forms, ranging from extended sessions with long-form material to brief, segmented encounters with shorter texts. These different modes of reading serve distinct purposes. Each imposes different cognitive demands and produces different outcomes. Understanding the strengths and limitations of both is necessary to fully assess the role of reading in a person’s intellectual and reflective life.

Extended Reading and Cognitive Development

Sustained reading over long periods enhances more profound engagement with complex material. This includes literary fiction, long-form nonfiction, and academic texts. These formats often require the reader to retain multiple ideas, track subtle developments, and reflect on information across several pages and chapters.

Cognitive studies have shown that this type of reading supports memory formation, comprehension, and critical reasoning. Reading literary texts in particular is linked to increased capacity for inference, attention to detail, and tolerance for ambiguity. Several studies have documented that continuous reading activates multiple areas of the brain, including those associated with language, memory, and imagination. These effects do not occur immediately but accumulate over time with consistent engagement with books and through extended reading.

Practical Value of Short-Form Reading

Short reading sessions, including those conducted on digital platforms, are more common in day-to-day routines. Although they do not produce the same depth of engagement as long-form reading, they still provide cognitive benefits.

Digital reading environments tend to encourage scanning and skimming. While this often results in superficial comprehension, it also helps readers develop the ability to filter information and identify key points quickly. These are valuable skills in information-dense contexts where time is limited. Furthermore, access to short-form material on phones or tablets has made reading more flexible and more widely available, especially for those who may not have time for uninterrupted sessions.

Research has found that reading for even a few minutes can reduce stress, support working memory, and help maintain mental alertness. This type of reading is also effective for acquiring factual information, staying updated on current events, or building general knowledge across different domains.

Complementary Approaches

Long-form and short-form reading serve different but complementary functions. A strong reading habit is strengthened by the ability to shift between modes as needed, rather than relying exclusively on one approach. Both forms require different types of attention and produce different kinds of value. Acknowledging the role of both promotes a more realistic and flexible comprehension of what it means to sustain a serious reading life in contemporary conditions.

Reading and the Structure of Solitude

Reading is often associated with solitude, but its relationship to loneliness is more complex. It is frequently assumed that people turn to books to escape isolation or fill emotional gaps. While that may be true in specific cases, reading does not eliminate loneliness. Instead, it provides a solitary structure—an activity that orders time, occupies attention, and produces continuity when other forms of connection may be unavailable.

Unlike social interaction, reading does not depend on reciprocity. It nurtures a sustained mental engagement without requiring participation from others. This makes it especially valuable for those who spend large portions of their time alone, either by circumstance or by choice. Reading provides structure to periods of solitude that might otherwise lack clear direction or purpose. While it does not replace interpersonal connection, reading offers a form of cognitive engagement that differs markedly from passive media consumption.

Ultimately, reading does not resolve the condition of being alone, but it gives definition to it. It organizes solitude into something purposeful. It offers engagement on different terms, instead of mere escapism. In periods of isolation, reading does not cure loneliness, but it can clarify the difference between being alone and being unoccupied.

The Material Presence of the Book

The physical book offers a kind of sensory richness that contributes subtly but significantly to the act of reading. The feel of the object, the slight give of the cover, the texture of the paper, and the spacing of the text all create a tactile rhythm that aligns with mental focus.

Even the layout of a printed page—where paragraphs fall, where a chapter begins, where a memorable line appears near a crease or margin—anchors memory to physical space. Readers often recall not only what they read, but where on the page it appeared and how it felt to hold the book open at that moment. The cover design, too, becomes part of this experience—not just as packaging, but as a visual threshold that frames the act of reading before the first sentence is even reached.

In contrast to the modern way of reading, texts that exist on digital screens are reformatted to suit the fluidity of devices. Pages no longer bear marks of wear, and touch is reduced to gesture. Reading devices can hold thousands of books, but they no longer weigh anything. While these formats expand access and convenience, they tend to bypass the rituals that once accompanied the act of reading: the deliberate pacing, the visual landmarks, and the physical cues that help structure and ground the experience.

The physical presence of a book gives reading a visible beginning, middle, and end, signaled by the shift of pages from first to the last. Margins encourage annotation. Covers gather wear that reflects repeated use. The subtle scent of paper, the tanning color of the pages and their deckled edges, and the slow softening of frequently turned pages all build a tactile continuity that deepens its value with every handling. A bookshelf filled with such objects is a library of your reading life’s memories.

A Life Structured by Reading

The commitment to reading regularly guides not only knowledge but also how we manage our focus, arrange our personal time, and interact with our surroundings. This practice has evolved from a simple pastime to a deeper integration with the framework of daily living. By making this choice, the reader establishes clear rhythms—dedicated time slots, favored book formats, and dedication to specific authors. These routines, once established, then govern the way we experience time and maintain our focus.

This systematic commitment is reinforced by the physical presence of books. Unlike digital counterparts, the printed volume offers fixed, sensory cues: measurable bulk, a defined length, and visible, tangible progress. These constant markers help forge a sense of continuity that extends well past the reading session. When these patterns are upheld over a long period, this duration supports the formation of strong cognitive habits, from sustained attention to reflective analysis.

To assert that reading is living is to claim that the act of reading integrates into the center of how one navigates time, thought, and memory. It is the salient mechanism that influences how we process information, handle solitude, and create purpose from everyday experience. The influence of reading is cumulative, by building patterns of thought that endure even when the book is closed. Reading does not simply accompany life; it should stand as the organizational structure of our daily life.

Further Reading

Reflections on the Reading Life by Bob on Books

Graham Norton: ‘The Bell Jar changed how I felt about books’ by Graham Norton, The Guardian

4 Modern Philosophy Books You Should Read by Mark Manson, markmanson.net

What books have shaped your life or philosophy on life? on Reddit