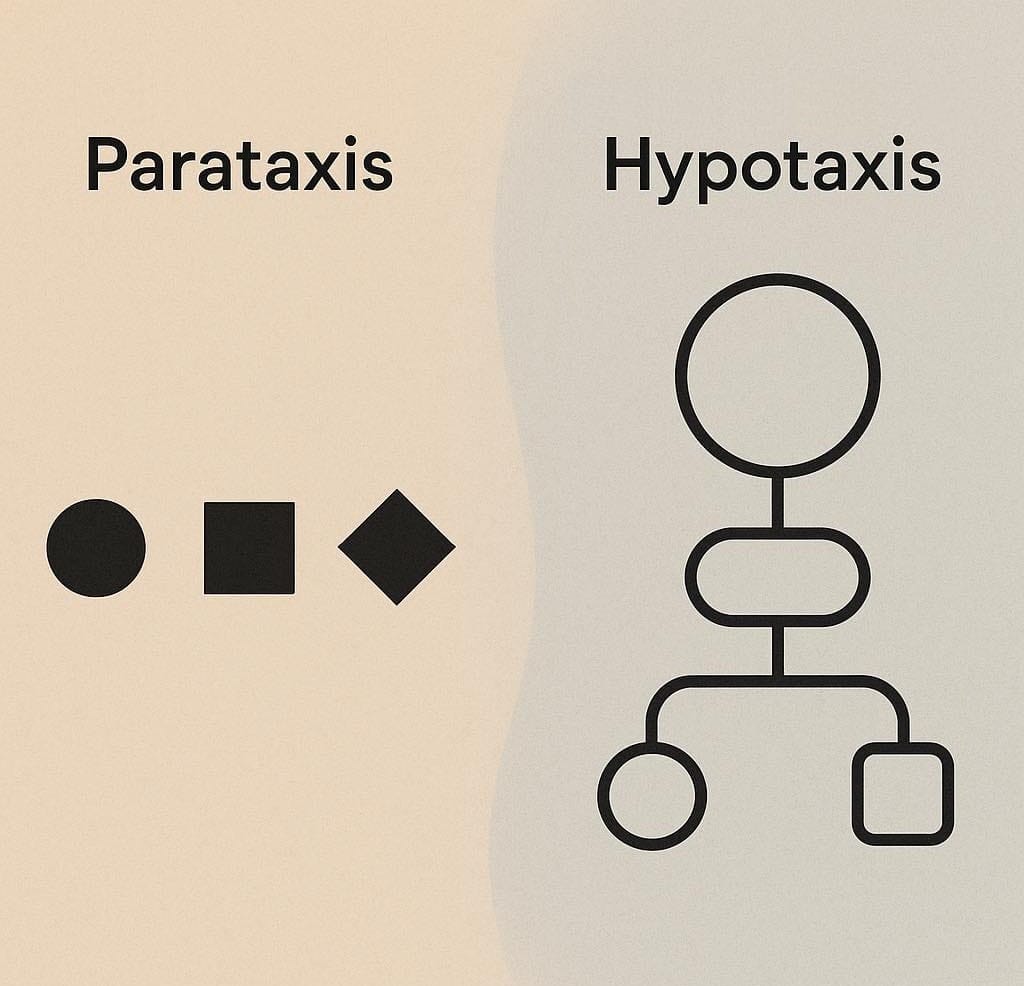

Every sentence arranges thought, yet not all arrangements follow the same rhythm or logic. Parataxis and hypotaxis are not just grammatical concepts but instruments of literary construction that determine how information is presented, how relationships are suggested, and how time, logic, and authority are embedded in the sentence structure.

In literary composition, parataxis and hypotaxis signal more than stylistic preference. They trace a structural contrast between coordination and subordination, openness and hierarchy. To grasp their difference is to see how syntax does more than carry content; it sets the terms by which thought finds its form.

Parataxis Defined

Parataxis (from Greek paratassein, “to place side by side”) is a writing style where clauses or sentences are placed one after another without using subordinating conjunctions to explicitly link them. In a paratactic construction, each clause is independent and of equal status (a coordinate construction rather than a subordinate one).

This means the logical or temporal relationship between ideas is not directly stated but left for the reader to infer. For example, saying “I came; I saw; I conquered” presents three actions side by side without indicating causality or chronology beyond their sequence. Paratactic prose often has an abrupt, additive quality, as the writer simply juxtaposes thoughts or images without overt explanation of how they connect.

Structural Characteristics

Paratactic sentences may use no conjunctions at all (relying on punctuation like commas or semicolons) or only coordinating conjunctions like “and” or “but”—never subordinating conjunctions like “because” or “although.” Crucially, each clause in a parataxis stands independently grammatically, without any syntactic dependence on another. This gives paratactic writing a “listing” or “stacking” effect, often mimicking a stream of consciousness or a rapid succession of observations.

The order of clauses in a parataxis can often be swapped without destroying the overall meaning, since no clause is hierarchically more important than another. Stylistically, parataxis can create a sense of speed, simplicity, or immediacy, as ideas pile up “one thing after another” for the reader to absorb all at once. This style is sometimes called an “additive” or “coordinate” style.

For a closer examination of another two related stylistic techniques, see our article on “Asyndeton vs. Polysyndeton.” The absence of conjunctions in paratactic constructions is a specific subtype known as asyndeton, while the repeated use of coordinating conjunctions, particularly “and,” is referred to as polysyndeton, a variant often associated with paratactic style.

Examples of Parataxis in English Literature

Writers turn to parataxis when they want to present a sequence of events, impressions, or facts without interpretation. In Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms (1929), the sentence “In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels” places images in succession without subordination. The coordinating “and” simply adds, never explains. The reader receives the scene as a whole, without cues about what to prioritize.

Similarly, Charles Dickens’ Bleak House (1853) opens with a chain of paratactic images: “Dogs, undistinguishable in mire. Horses, scarcely better; splashed to their very blinkers.” Each unit stands alone, contributing equally to the atmospheric buildup without a guiding hierarchy. The diffuse, encroaching, and indistinct structure mimics the fog where it hangs.

In contemporary fiction, parataxis creates emotional immediacy. Raymond Chandler in Farewell, My Lovely (1940) writes: “I needed a drink, I needed a lot of life insurance. I needed a vacation, I needed a home in the country.” The sentences’ impact comes from repetition and equal emphasis. No clause is marked as more important than another, and their accumulation defines the tone.

Contrasting Hypotaxis

Hypotaxis (from Greek hypó, “under” + taxis, “arrangement”), by contrast, is a style of sentence construction in which clauses are arranged in a hierarchy of subordination, with linking words that explicitly indicate the relationship between them. In a hypotactic sentence, one clause is the main clause, and others are dependent (subordinate) clauses that elaborate on it, using subordinating conjunctions (e.g., because, although, when, if) or relative pronouns (who, which, that).

This style “stacks” ideas in a complex, layered structure, clearly signaling which information is primary and how supporting details or clauses are connected. For example, “I am tired because it is hot” is a hypotactic construction: the use of “because” subordinates the cause (heat) under the main statement (tiredness), explicitly showing a cause-and-effect relationship. By contrast, a paratactic version (“I am tired; it is hot”) would simply juxtapose those facts without indicating the causal link. Thus, hypotaxis overtly organizes the logic or chronology in a sentence through syntax.

Structural Characteristics

A hypotactic sentence often takes the form of a complex sentence (or a string of complex clauses) where additional information is embedded within or after the main clause. It commonly employs multiple levels of subordination, creating a hierarchy of information. Subordinating conjunctions (after, since, although, if, while, etc.) introduce dependent clauses that cannot stand alone, making their meaning conditional on the main clause.

Relative clauses (starting with who, which, that) are another hypotactic device, adding descriptive or qualifying information to a noun. Because of this layering, hypotactic style is sometimes called a “subordinating style.” The syntax often results in longer, more intricate sentences that spell out logical, temporal, or causal relationships between ideas.

The etymology (Greek for “beneath arrangement”) reflects how subordinate elements are placed “under” the main statement in importance. Stylistically, hypotaxis tends to create a more formal, analytical, or reflective tone, as the writer is guiding the reader through a structured chain of thought. It can convey nuance and precision by qualifying statements and showing how ideas interrelate (for example, indicating which events happened because of which, or when and how something occurred, all within one sentence).

Examples of Hypotaxis in English Literature

F. Scott Fitzgerald, in The Great Gatsby (1925), employs hypotaxis to inform narrative timing and mood: “When I looked once more for Gatsby he had vanished, and I was alone again in the unquiet darkness.” The subordinate clause introduced by “when” sets a temporal frame that anchors the emotional shift. The structure draws attention to absence and solitude; it guides the reader through events and reflections in a single, continuous sentence.

Jane Austen, in Pride and Prejudice (1813), uses hypotaxis to map emotional rhythm onto setting: “Elizabeth, as they drove along, watched for the first appearance of Pemberley Woods with some perturbation; and when at length they turned in at the lodge, her spirits were in a high flutter.” The subordination introduced by “as” and “when”defines the pacing of perception and response. The sentence progresses gradually; it tracks the character’s anticipation with measured control.

In “The Raven” (1845), Poe writes: “While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping…” This opening uses a subordinate clause introduced by “while,” setting a temporal condition before the main clause (“there came a tapping”). The subordinate clause cannot stand alone and directly frames the timing of the main event. This syntactic structure clearly establishes the relationship between the narrator’s drowsiness and the eerie interruption.

Historical and Stylistic Use in Literature

The preference for parataxis or hypotaxis often reflects stylistic traditions, aesthetic intentions, or even cultural tendencies in narrative structure. Ancient Greek literature favored paratactic structure, especially in early epic and lyric poetry. Homer’s lines in The Iliad often proceed through loosely connected images and actions, granting a rhythmic openness and oral fluidity.

Classical Latin, and later the stylized prose of Cicero, moved toward hypotaxis. The Renaissance and neoclassical eras maintained this preference for complex subordination, which emphasized logic and clarity.

By the 20th century, many modernist and postmodernist writers embraced parataxis as a mode of fragmentation, simultaneity, or irony. Gertrude Stein’s declarative repetitions and Ernest Hemingway’s crisp clauses exemplify how parataxis can reflect immediacy and surface. Meanwhile, William Faulkner’s dense hypotactic passages in Absalom, Absalom! (1936) show how subordinated syntax can mirror psychological entanglement and temporal complexity.

Further Reading

Parataxis on Wikipedia

Hypotaxis on Wikipedia

Refine Your Writing Style with Hypotaxis and Parataxis by Writing with Andrew, YouTube