Metonymy and synecdoche are not just rhetorical figures tucked away in grammar textbooks; they are essential tools in the language of literature, journalism, politics, and everyday speech. Each offers a unique way to condense expression, shift emphasis, or redirect a reader’s attention through linguistic substitution. Though often confused, their functions diverge in both intent and effect.

This article explores metonymy and synecdoche by defining their distinctions, examining their overlap, and illustrating their power through well-known examples.

What is synecdoche?

Synecdoche names a substitution in which a part stands in for the whole, or the whole stands in for a part. It works on a relationship of physical inclusion: something is represented by one of its components or by a broader category to which it belongs.

Examples of Synecdoche

- All hands on deck.

Here, “hands” refers to sailors. The part (hands) substitutes for the whole (persons). - The White House issued a statement.

This use flips the formula. The whole building stands for the people working inside it. - She had three mouths to feed and barely enough to survive.

In this sentence, “mouths” represents people which is again, a part symbolizing a whole.

Synecdoche compresses physical detail into linguistic economy. It is efficient, visual, and often visceral. It can express urgency, embodiment, or reduction in a single word.

What is metonymy?

Metonymy, on the other hand, substitutes a term with another that is conceptually linked but not necessarily a part of it. The relationship is not one of inclusion but of association: cause for effect, instrument for action, institution for person.

Examples of Metonymy

- The crown will decide your fate.

Here, “the crown” stands for royal authority, not a literal object worn on the head. - He drank the whole bottle.

What’s consumed is not the bottle itself, but the liquid it contains. - The pen is mightier than the sword.

“Pen” represents writing or diplomacy, while “sword” stands for military force.

Metonymy can convey abstraction with a physical marker. It roots intangible ideas in tangible objects, turning systems and institutions into things a sentence can carry.

Metonymy vs. Synecdoche: Key Differences

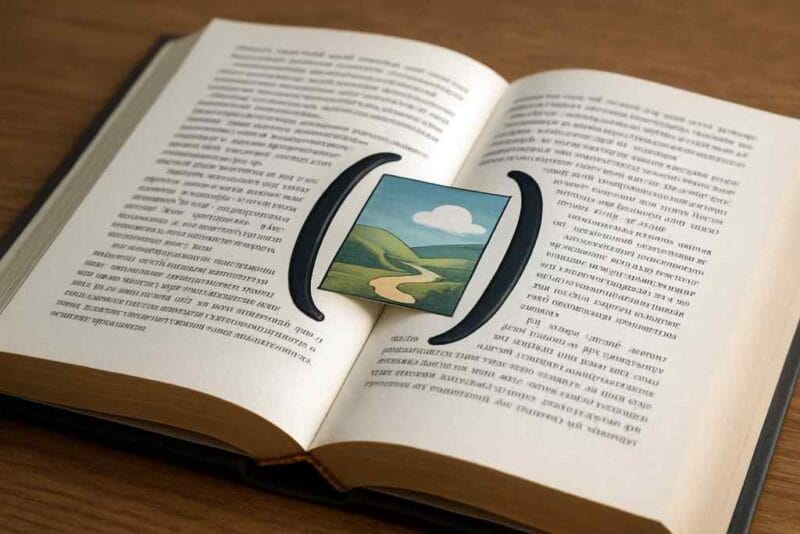

Despite their surface similarity (both involve substitution), the distinction lies in what kind of relationship connects the term used and the term meant. A synecdoche is always a subset or superset. A metonymy need not be.

| Category | Synecdoche | Metonymy |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship Type | Part–whole or whole–part | Conceptual or causal association |

| Type of Substitution | Physical inclusion | Mental or habitual linkage |

| Example | “Wheels” for “car” | “Hollywood” for “film industry” |

| Effect Produced | Compression, embodiment | Abstraction, institutional presence |

Overlap and Ambiguity

Some expressions defy neat categorization. Consider the phrase “He’s got a good head on his shoulders.” While “head” may imply synecdoche (a part of the person), it also connotes intellect, which aligns with metonymy. In practice, many instances exhibit properties of both.

Writers rarely signal which device they are using. Meaning, then, depends on context, convention, and interpretive tilt. This overlap is not a flaw but a feature. It reveals how figurative language thrives on porous borders and elastic thinking.

Why Writers Use These Figures

Both metonymy and synecdoche give writers a way to compress expression without flattening texture. They can add vividness, redirect focus, or make abstract themes concrete. In literature, such substitutions often carry emotional or ideological charge.

- Synecdoche can humanize or dehumanize. A body reduced to “hands,” “eyes,” or “legs” may suggest labor, surveillance, or movement.

- Metonymy can displace blame or authority. Saying “the markets reacted violently” detaches volatility from individual agents and attributes it to an abstract entity.

These choices are rarely neutral. They shape not just style, but worldview.

Famous Uses in Literature

- In William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar (1599), Mark Antony says, “Lend me your ears,” a classic synecdoche—ears standing for attention.

- In George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945), “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others” plays with institutional metonymy—“animals” representing social classes and political systems.

- In T. S. Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock (1915), the line “I have measured out my life with coffee spoons” employs metonymy to imply monotonous habit, substituting a small object for a larger existential claim.

These examples show how both devices enrich not only style but implication, carrying tone and theme through the smallest pivot of language. Writers depend on for leverage, not just for elegance. Within a sentence, a symbol unfolds into a system, a part expands into a whole, and the reader is drawn into their momentum.

The distinction between metonymy and synecdoche hinges on whether the substitution is part-whole (synecdoche) or associated-idea (metonymy). Both are indispensable because they do more than decorate language; they compress, reroute, and sometimes disguise. They help language do what it often must: speak indirectly when direct speech would falter, simplify what cannot be named outright, or reframe power through substitution.

Further Reading

Metonymy on Wikipedia

Synecdoche on Wikipedia