Explore This Topic

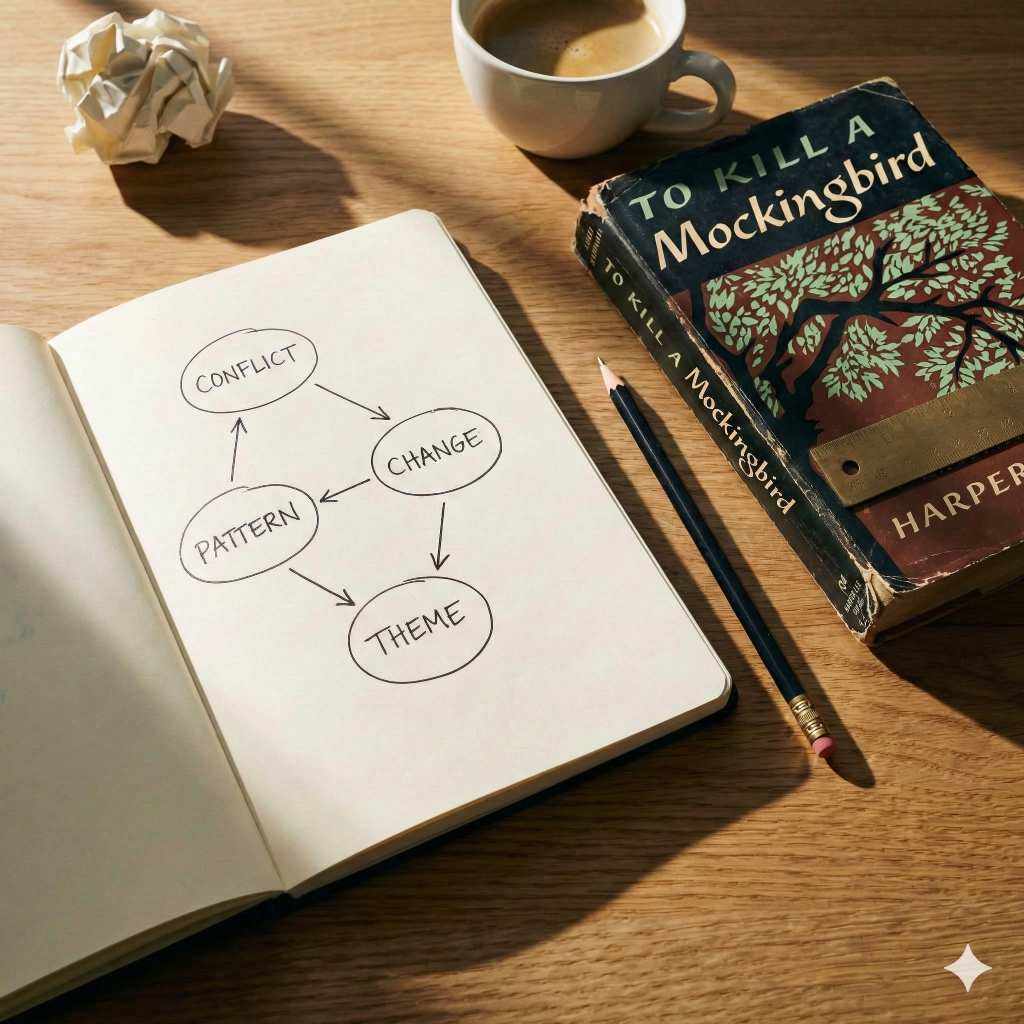

Identifying a literary theme should not be construed as an act of discovery; it is rather a process of analysis. The theme is not a hidden message waiting to be found but the coherent argument a narrative constructs through its conflict, character transformations, and formal patterns. To identify a theme is to reverse-engineer this construction.

This article provides a replicable method for that analysis. It moves beyond narrative events to a thematic statement by examining the central problem a text establishes, the changes it orchestrates, and the patterns it deploys. This method applies the core principle that a theme functions as a narrative’s operative logic—a principle examined in our central guide, Themes in Literature: A Definitive Guide.

The Foundational Step: Isolate the Central Conflict

Thematic analysis begins by identifying the narrative’s central tension. First, we must move beyond the surface action to determine the conceptual problem the story is trying to explore. This conflict is rarely a simple physical battle, however; it is a clash of values, desires, or states of being.

Next, formulate the conflict as a dialectic. In Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (1960), the core conflict is not just having Atticus Finch against Bob Ewell. It is the tension between an individual’s ethical reasoning and a community’s entrenched prejudice. In George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), the conflict manifests as the individual’s need for autonomous consciousness against the state’s project of erasing it.

This initial formulation provides the framework for all subsequent analysis. The characters, plot developments, and symbolic patterns will each apply pressure to this central problem. By then, the theme will emerge as the narrative’s implied resolution or commentary upon it.

Trace the Arc of Transformation

With the central conflict defined, examine how the narrative tests and resolves this tension through character. The protagonist’s trajectory often serves as the story’s primary thematic argument. Determine whether the character’s perception, values, or fundamental situation changes as a result of the conflict.

Analyze the nature and direction of this change. In Shakespeare’s Macbeth (1623), the protagonist’s transformation from loyal general to tyrannical ruler presents a specific argument: ambition severed from morality consumes the self. Conversely, in Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol (1843), Ebenezer Scrooge’s radical metamorphosis from miser to philanthropist posits that human nature can redeem itself through empathetic connection.

This transformation, however, is not always redemptive. A character’s failure to change, or their destruction, constitutes an equally powerful thematic statement. The key is to locate what the narrative asserts about the possibility of resolution within its constructed world. This trajectory demonstrates the consequences of engaging with the central conflict.

Map the Patterns: Motifs and Recurrences

The narrative’s systemic design becomes visible through its repetitions. Move from analyzing singular events to cataloging recurring elements; for example, a specific object, a type of environment, a repeated phrase, or a visual image. These motifs are not incidental; they apply concentrated pressure to the central conflict by highlighting its dimensions and stakes.

In F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925), the green light across the bay recurs as a tangible manifestation of Gatsby’s unreachable ideal. Its repeated appearance sharpens the conflict between his aspirational dream and the immutable reality of his past and present. In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), the motif of fire and ice consistently frames the tension between the compulsive pursuit of knowledge and the essential conditions for human connection and safety.

By mapping these patterns, you identify the narrative’s method of emphasis. These recurring elements function as the text’s own analytical tools, directing attention to the critical facets of its central problem. Distinguishing this technical operation (i.e., the work of a motif) from the core theme is a necessary analytical step, examined in our guide to motif versus theme.

Articulate the Argument

Finally, synthesize your observations from the preceding steps into a definitive thematic statement. A theme is not a single word or topic but a coherent, arguable proposition about the narrative’s central conflict. Use the evidence of transformation and pattern to formulate this proposition.

A strong thematic statement follows a clear logic: “[Text] argues that [proposition about the human condition/central conflict]. For example, analysis of Macbeth might yield: “The play argues that ambition severed from moral constraint inevitably annihilates the self.” A study of To Kill a Mockingbird could conclude: “The novel contends that individual conscience must act as an antagonistic presence within communal injustice, even in the absence of immediate victory.”

This articulation is the final product of your analysis. It moves from observation to interpretation, providing a focused lens that clarifies the relationship of each narrative component to the central argument. For further examples of this method applied across different literary forms, consult the article, Literary Themes Examples: An Analytical Index, and our guide to Themes in Poetry: An Analytical Guide.

Analysis as a Critical Lens

The method outlined here (isolating conflict, tracing transformation, mapping patterns, and articulating the argument) transforms reading from passive consumption into active critical engagement. This process does not simply uncover a single correct theme but constructs a verifiable interpretation based on the text’s own structural evidence.

By mastering how to use this analytical lens, you can engage with literature at the level of its design. You shift from asking what a story is about to examining how it makes its case about the world. This practice applies to narrative forms beyond the novel, from drama and poetry to film. The underlying principle remains: a theme is a function of a work’s operative logic, a premise fully elaborated in our central theoretical guide, Themes in Literature: A Definitive Guide.

Further Reading

How to Find Your Story’s Theme Without Forcing It by Famous Writing Routines

A Handy Strategy for Teaching Theme by Zach Wright, Edutopia

How can you find theme in a story? on Quora