Women’s fiction refers to novels built around a protagonist’s emotional transformation. In many cases the lead is a woman, and the genre often highlights fictional women characters navigating change, but the emphasis rests less on gender than on the depth of the character’s personal journey.

Some critics argue the term is too narrow, since it reinforces the idea that only women will find such work meaningful, when in fact stories of transformation can appeal to any reader. The Women’s Fiction Writers Association describes it more openly: the focus is on a character’s inner journey, and that emphasis can stretch across genres, and in any time period. Alternatives like “emotional journey fiction” or “relationship fiction” have been suggested as more inclusive.

Core Traits of Women’s Fiction

While definitions vary, certain qualities appear consistently in works placed under this label. These books revolve around inner change, often mapping the terrain of relationships, identity, and belonging. Such traits reveal why the term has endured despite the debate around it.

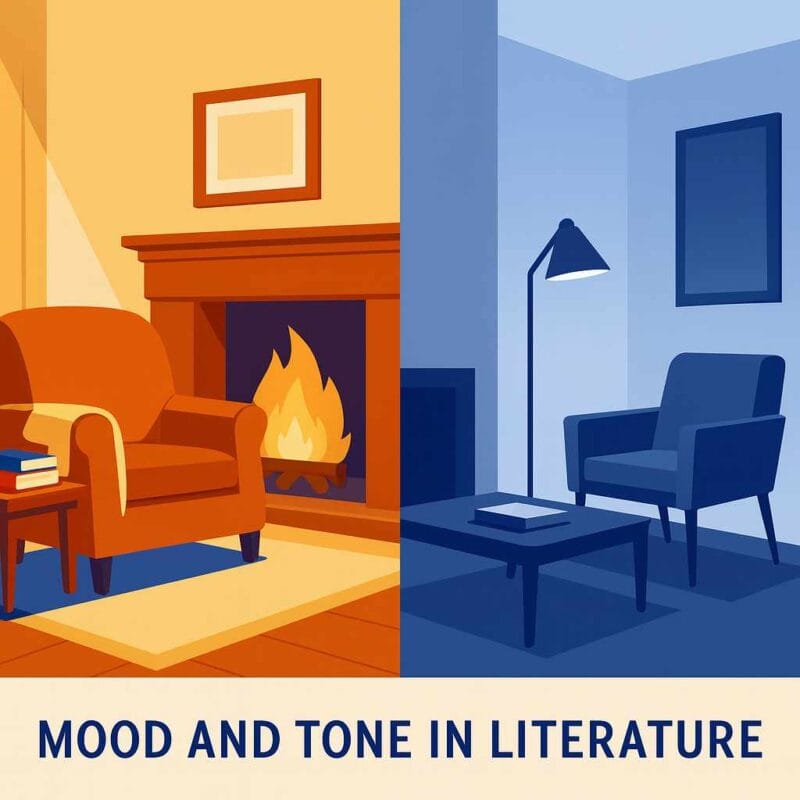

Emotional Journey

At the heart of women’s fiction lies the emotional journey—growth that alters how the protagonist engages with the world. The term “fictional women characters” often connects with this genre, though women’s fiction is about transformation more than gender alone.

These characters may grapple with loss, identity, family obligations, societal roles, or internal misbeliefs. Many examples feature everyday struggles rendered with clarity and friction, pressing the story beyond mere plot mechanics.

Fictional Women Characters

In women’s fiction, female leads often carry the story. They are portrayed with nuance and individuality, rather than as background figures. Common portrayals include:

- Mothers and caretakers – characters balancing nurturing roles with personal sacrifice or hidden aspirations.

- Professionals – women facing conflicts between ambition, independence, and societal pressures.

- Partners and spouses – those navigating the shifting ground of marriage, separation, or new love.

- Women in transition – individuals confronting loss, rediscovering identity, or embarking on late-life change.

- Everyday lives in extraordinary moments – ordinary characters drawn into crises that force transformation.

Alongside these general portraits, literature has produced iconic women who continue to define how such characters are imagined:

- Jo March (Little Women by Louisa May Alcott, 1868–69) – Independent, ambitious, and torn between family obligations and personal freedom.

- Elizabeth Bennet (Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen, 1813) – Intelligent and self-possessed, challenging the constraints of marriage and class.

- Celie (The Color Purple by Alice Walker, 1982) – A voice of survival and eventual empowerment, moving from oppression to self-assertion.

- Anna Wulf (The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing, 1962) – A writer whose fractured life embodies questions of identity, creativity, and politics.

- Offred (The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood, 1985) – A figure of endurance and resistance within a dystopian regime.

- Marian McAlpin (The Edible Woman by Margaret Atwood, 1969) – A young woman confronting social expectations and consumer-driven identity.

These figures highlight the range of struggles and transformations that make women’s fiction both varied and timeless.

Case Study: March by Geraldine Brooks

A closer look at Geraldine Brooks’ March (2005) demonstrates how women’s fiction can extend beyond its most obvious boundaries. Though it centers on a male lead, the novel captures the essence of the genre by focusing on conviction, loss, and renewal. It offers a useful example of how emotional journeys define the category more than gender alone.

March reimagines Little Women’s absent father and explores his Civil War experiences and psychological conflict. Brooks drew inspiration from Louisa May Alcott’s own father, Amos Bronson Alcott, resulting to a portrait of a man whose ideals strain against the horrors of war. The novel won the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.

Despite its male protagonist, March aligns with women’s fiction by tracing a personal transformation forged by belief, grief, and survival. The novel derives its power not from battle scenes, but from a meditation on relationships and convictions. These elements establish a clear kinship with stories often labeled within the genre.

Women’s Fiction and Related Labels

This term operates not in isolation but alongside, and often in tension with, labels such as chick lit, feminist fiction, and upmarket fiction. Examining these related categories illuminates their overlaps and contrasts. It also reveals how marketing pressures and cultural debates dictate classification.

- Feminist Fiction: Feminist fiction shares goals with women’s fiction but its focus lies explicitly on gender politics, empowerment, and critique. While women’s fiction may engage with gender implicitly through emotional arcs, feminist fiction foregrounds critique of patriarchal structures. Many works blend the two, but they remain distinct in intent.

- Literary and Upmarket Fiction: Women’s fiction occupies a spectrum from commercial to literary. Upmarket titles such as Me Before You (2012) or Daisy Jones & the Six (2019) carry accessible storytelling with richer themes. When a work adopts innovative language or stylistic experimentation, it may cross into literary fiction, shedding the women’s fiction label even if emotional preoccupations remain central.

- Romance vs. Women’s Fiction: Romance novels focus on a central love story and the expectation of a happy ending, following genre-specific arcs. Women’s fiction can incorporate a romantic thread, but its purpose lies in the protagonist’s broader emotional shift, not romance as a narrative foundation.

Labels influence how books are promoted, shelved, and perceived. They can guide readers toward works that speak to them, but they can also oversimplify or diminish complex stories. Looking at the strengths and shortcomings of such terms helps explain why they persist and why many authors continue to challenge them.

Further Reading

Women’s Fiction, Chick Lit, and Other Thoughts on Labels by Robyn Harding, Writer’s Digest

Don’t patronise popular fiction by women by Harriet Evans, The Guardian

What Do We Mean When We Say Women’s Fiction? by Liz Kay, Literary Hub

Blame it on the Book Cover by LuAnn Schindler, Wow! Women on Writing