Spoilers ahead

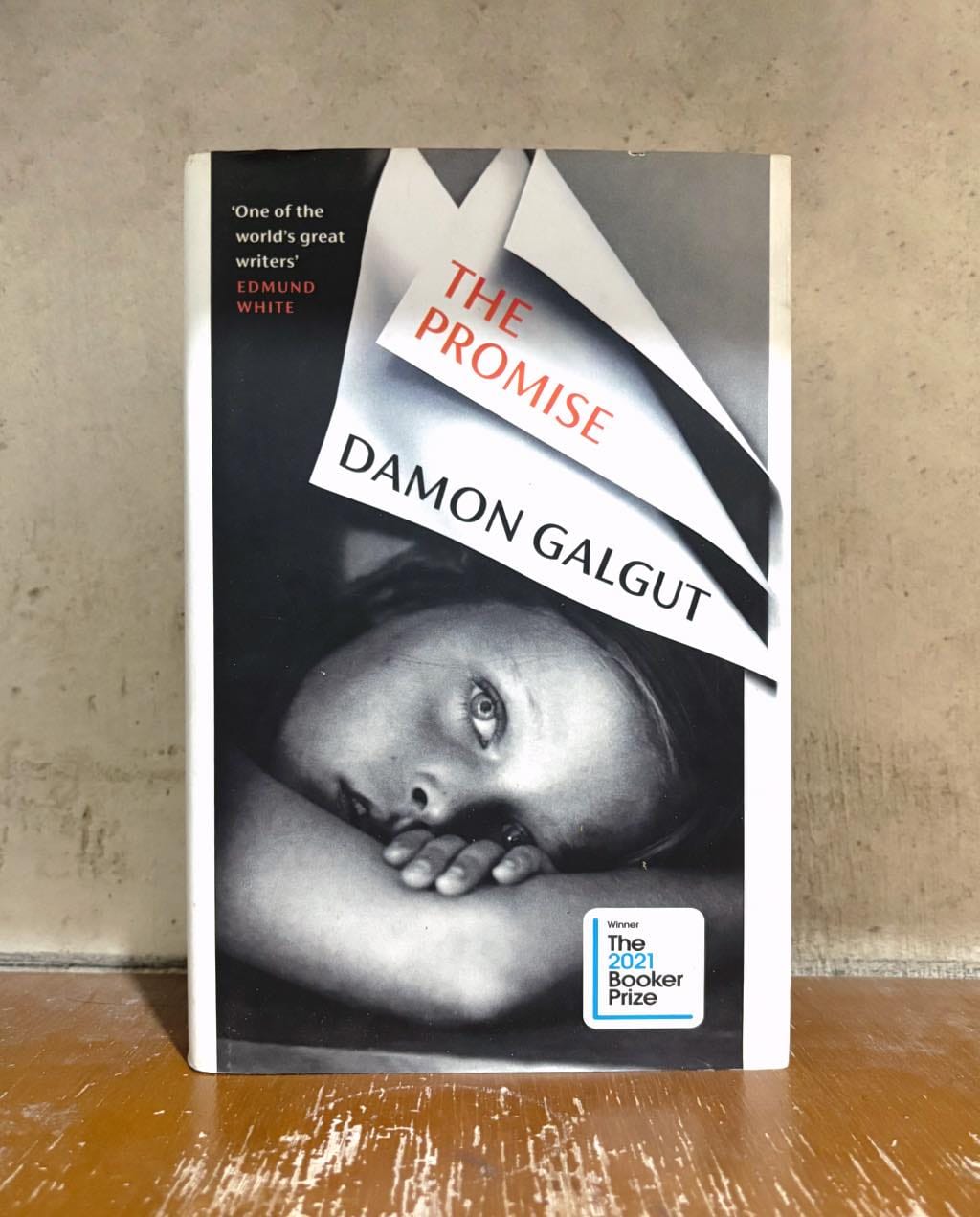

In The Promise (2021) by Damon Galgut, the passage of time is marked not by milestones but by funerals. Set against the backdrop of South Africa’s fraught transition from apartheid to democracy, the novel compresses multiple decades into four tightly written chapters. Structured around four deaths across the decades, the novel maps the slow disintegration of a white South African family in the post-apartheid era.

The Swart family functions as a closed household where personal neglect, moral evasion, and inherited privilege persist alongside a nation’s unresolved past. At its center rests a neglected promise: a pledge made by the dying matriarch to transfer ownership of a small house to Salome, the Black domestic worker who devoted most of her life to the household. The surviving members disregard this obligation, and that sustained refusal becomes the novel’s defining thread.

Winner of the 2021 Booker Prize, Galgut’s novel is a compact yet searing meditation on family, history, and the accumulated burden of promises broken over generations. What appears modest in scope—a family’s refusal to honor a dying woman’s word—unfolds into a wider account of avoidance, deferment, and ethical paralysis.

Damon Galgut and the Post-Apartheid Novel

Galgut was already a distinguished figure in South African literature before The Promise, but this novel presents his most sustained treatment of post-apartheid disillusionment. His earlier works—particularly The Good Doctor (2003) and In a Strange Room (2010)—had already established his interest in dislocation and moral ambivalence. Here, he sharpens those established concerns, examining not just the failures of private citizens but also the national evasions that have decided the country’s identity.

The Swart family stands in for a particular demographic—white, Afrikaans-adjacent, neither especially rich nor politically engaged. They are not powerful enough to manipulate history, but they are well-placed to ignore its demands. In this, they resemble a broader post-apartheid society that has chosen forgetting over accountability.

Where earlier South African novels often approached the end of apartheid through revolution or reconciliation, Galgut adopts a more restrained and corrosive perspective. He avoids calls for dramatic change and instead reveals the social arrangements that block it. The Swart family functions through evasion rather than malice. Their failure to honor a simple vow becomes a small-scale reflection of a broader national inability to confront its historical record.

Structure and Style: Four Deaths and the Shape of a Nation

The novel’s narrative structure refuses a stable chronology. Time leaps forward between sections, while the intervening years appear only in fragments. Galgut employs an omniscient voice that moves across characters and occasionally addresses the reader. The result is a style that feels both intimate and alienating. This technique mirrors the broken contours of memory and historical record.

The Funeral as Narrative Anchor

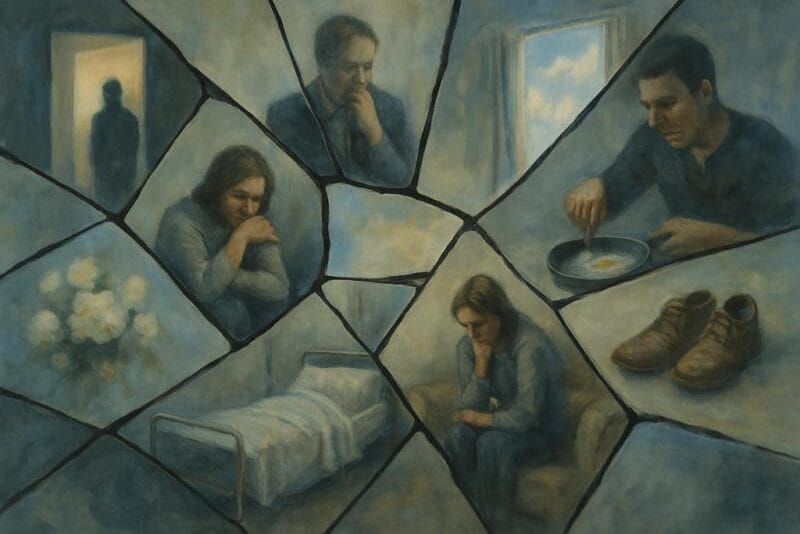

Each section of The Promise opens with a funeral, a structural choice that lends the novel a rhythm both ritualistic and disjointed. The deaths—first Rachel (mother), then Manie (father), followed by Astrid (second child) and Anton (eldest child)—punctuate the family’s history, marking not transformation but attrition. Galgut does not present these deaths as climactic events. Instead, they serve as entry points into a version of time that advances by omission. What occurs between them is rarely dramatized. The reader is given only the consequences, not the developments that led to them.

This structure mirrors the way both family and nation move forward without addressing unresolved foundations. Between deaths, the family grows smaller through separation rather than through open conflict, with the promise made at Rachel’s deathbed remaining unresolved for decades. No one actively blocks it. But because it was consistently deferred, it was overshadowed by routine matters and a refusal to act until it was nearly too late.

Dislocated Perspective and Narrative Drift

Galgut employs a shifting third-person perspective that rarely comes to rest. The narration moves in and out of characters’ thoughts, often within the same sentence, without warning or typographical signal. This exacting form of free indirect discourse enables the narrator to absorb the vocabulary, prejudices, and rhythms of a character’s inner life while maintaining an external vantage point. Characters are observed both from within and from a distance, their perceptions interwoven with the narrator’s voice but never fully aligned with it. The result is a tone that withholds intimacy while exposing vulnerability.

This dislocated perspective mirrors the novel’s thematic focus on avoidance. No single character holds the narrative; no one voice is privileged. Instead, the text oscillates between voices, sometimes sarcastic, sometimes elegiac, sometimes flatly observational. While Galgut never commits to a full stream of consciousness, certain passages carry its influence, particularly in their momentum and elasticity. The style remains consistent throughout—measured, precise, and unsentimental—mirroring the emotional reserve that defines the Swart family. The fragmented point of view becomes a formal expression of the novel’s deeper concern: the difficulty of maintaining a stable sense of self, memory, or duty in a country preoccupied with forgetting and moving on.

Thematic Reflections on Post-Apartheid South Africa

The themes of The Promise emerge through restraint rather than overt statement. Galgut works through structure and sustained emphasis to convey the pressures bearing on both the Swart family and the society around them. These themes do not arrive as lessons. They surface as conditions that persist and influence conduct over time.

Deferred Justice

The novel’s central question, whether the promise made to Salome will ever be fulfilled, extends across decades of hesitation and inaction. The house remains modest in scale and occupied, yet ownership never transfers. Salome continues to live on the property, though her claim receives no formal recognition. Each family member who inherits the land sidesteps the issue rather than confronting it directly. Their indifference carries no overt hostility; it is procedural, buried in paperwork and deferred conversations. Galgut situates the reader within this prolonged delay, where every chance for resolution slips away through habitual neglect.

Even when movement occurs, it does not erase what came before. The long pause between promise and fulfillment hollows out any sense of closure. The narrative hints at final gestures and late attempts at reparation but does so without granting emotional vindication. If justice arrives, it arrives diminished, sidelined by time and stripped of symbolic power. The novel does not ask whether the promise is kept, but whether it matters when its fulfillment finally arrives.

Obligation and Evasion

Throughout The Promise, evasion functions as reflex rather than as a calculated choice. The Swart siblings do not confront their mother’s wish; they leave it unattended. Amor, the youngest, refuses to forget, yet her persistence is treated as an inconvenience rather than a virtue. The others acknowledge the legitimacy of the promise while declining to accept responsibility for it. Galgut traces this pattern with precision. He refrains from casting his characters as villains, and through that restraint exposes a more unsettling reality: responsibility erodes with ease when no one feels compelled to assume it.

By the end of the novel, the consequences of delay remain visible, even as an effort is finally made to honor the promise. The transfer of the house does occur, yet Galgut offers no suggestion that this act restores what was lost. What could have been settled decades earlier takes place only after the original intent has been worn down by time and neglect. Ownership changes hands, but the damage produced by years of avoidance is not undone. Obligation, in Galgut’s account, is not dramatized as conflict; it appears as something conveniently put aside, left for someone else to resolve.

Inheritance and Silence

Inheritance in the novel functions on two planes. Material assets pass through the Swart family by law and custom, largely unchallenged. Moral inheritance, however, proves far more difficult to negotiate. Rachel’s promise, while unrecorded, becomes the axis on which the family’s integrity is tested. No will contains it. No legal mandate enforces it. Its only power lies in memory, and memory proves a fragile custodian. Over time, the siblings’ accounts shift. The original clarity of Rachel’s intent becomes subject to doubt, then to indifference.

Silence becomes the novel’s most persistent response. Salome rarely speaks, and when she does, her words carry no authority in the eyes of the family. She waits without protest. Her position reflects the absence of any channel through which her claim can be acknowledged. Even at the point where action is finally taken, the silence is not broken. What has been withheld is offered, yet no one speaks of what was lost in the delay.

Memory and Forgetting

In the book, memory is unreliable, malleable, and often self-serving. Rachel’s final words, once vivid to Amor, become blurred in the family’s collective account. Each retelling weakens the original claim, making those who benefit from inaction doubt its authenticity. Galgut’s narrative structure, with its temporal gaps and indirect narration, mirrors this process. What happened is less important than how it is remembered, and that distinction governs the novel’s emotional tone.

This erosion of memory also reflects a broader national mood marked by fatigue and revision. South Africa’s transition called for public acts of remembrance, yet over time those acts grew symbolic rather than operative. Galgut’s characters embody this shift. They acknowledge the past only in fragments, and even those fragments undergo softening through interpretation. The longer the promise remains unfulfilled across years, the less its origin matters. What began as a clear commitment drifts into dispute, becoming easier to disregard than to honor.

The National Implication of the Broken Promise

While The Promise is centered on a single family, its implications extend far beyond the Swarts. The novel’s title refers to more than a spoken vow. It gestures toward the broader failure to translate political liberation into meaningful restitution. The promise of a new South Africa—just, equal, repaired—remains suspended.

The house at the edge of the property is on a minor piece of land. Its legal transfer would not alter the family’s position in any substantial way. Yet their reluctance to act reveals the deeper structures at play. The refusal is not material; it is symbolic. To recognize Salome’s claim is to acknowledge the historical foundation of that claim and, by extension, the unearned nature of their own inheritance.

By the novel’s end, Salome receives legal ownership of the house, decades after the promise was first made. The transfer, while official, arrives so late that it carries little sense of resolution. Galgut closes the novel through restraint rather than triumph. The fulfilled promise remains as a subdued gesture whose significance has already begun to fade.

Selected Passage with Analysis

But Amor can see her through the window, so she’s not invisible after all. Thinking about a memory, not understood till now, of an afternoon just two weeks ago, in that same room, with Ma and Pa. They forgot I was there, in the corner. They didn’t see me, I was like a black woman to them.

Page 19, The Promise by Damon Galgut

Amor looks through the window and sees Salome standing outside. The sight recalls a moment from two weeks earlier, when Rachel, already dying, asked her husband Manie to give Salome ownership of the house she had long occupied. Amor had been in the room during that conversation, seated quietly in the corner. Her parents had forgotten she was there. At the time, the scene seemed distant to her, but now, in light of Rachel’s death and the funeral, it returns with greater clarity.

The quote — “They didn’t see me, I was like a black woman to them” — draws a direct line between Amor’s brief invisibility and Salome’s continual erasure. In that moment, Amor begins to understand the difference between presence and recognition. She had occupied the same space as her parents, but they had spoken as if she did not exist. The memory forces her to recognize that Salome has lived in that condition for years, serving the family while remaining unseen.

Galgut uses free indirect discourse to fold Amor’s thoughts into the narration without clear transition. The line arrives softly, without framing, echoing the way Salome’s presence has been overlooked for years. This stylistic choice mirrors the novel’s deeper concern: some truths are not spoken aloud, unnoticed until they surface. Amor’s recognition emerges not as a turning point, but as something embedded in the narrative — present from the start, though only now coming into focus.

Further Reading

Damon Galgut on Confronting South Africa’s Racist History With Booker-Winning The Promise by Eloise Barry, Time

Booker Prize: Damon Galgut’s The Promise is a reminder of South Africa’s continued and difficult journey to a better future by Daniel Conway, The Conversation

Damon Galgut on his Booker winner The Promise: ‘Death sets things off’ by Frederick Studemann, Financial Times

‘African writing should be taken seriously’: Damon Galgut, winner of the 2021 Booker Prize by Nawaid Anjum, Substack