Consider the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock, the white whale, the scarlet letter. These objects become focal points where a narrative’s logic condenses. A literary symbol gathers associative charge with each appearance; this accumulation operates as a form of instruction. The reader learns to watch for it, to see the ordinary object, such as a conch shell or a glass figurine, progressively assume the role of a story’s central argument.

This is symbolism: the language a text uses when it wishes to speak indirectly. It establishes a connection between the visible surface of a plot and the submerged patterns of thought beneath. To interpret a symbol is to follow this connection, to understand how a recurring element can come to organize one’s perception of the work as a whole.

Defining Symbolism in Literature

Symbolism constitutes a foundational literary device. It establishes a resonant relationship between a concrete element within the text and an abstract concept external to it. A green light across a bay, a white whale, a scarlet letter—these objects become focal points for interpretation. They operate as anchors for thematic gravitas by transforming narrative detail into conceptual signal.

This literary device relies on contextual reinforcement. A single mention of a rose is a detail; a rose that appears at a wedding, withers on a grave, and is pressed between the pages of a journal becomes a symbol. Its representational power is built through repetition, variation, and placement. The symbol’s efficacy depends on this integration. It must function seamlessly as a component of the plot or setting while simultaneously generating a parallel track of significance. This dual operation distinguishes literary symbolism from allegory, which depends on fixed correspondence. The symbol maintains an open quality, its suggestiveness arising from its complete integration into the narrative’s structure.

Types of Symbolism in Literature

Symbolism manifests through several distinct channels. Recognizing these categories refines analytical precision.

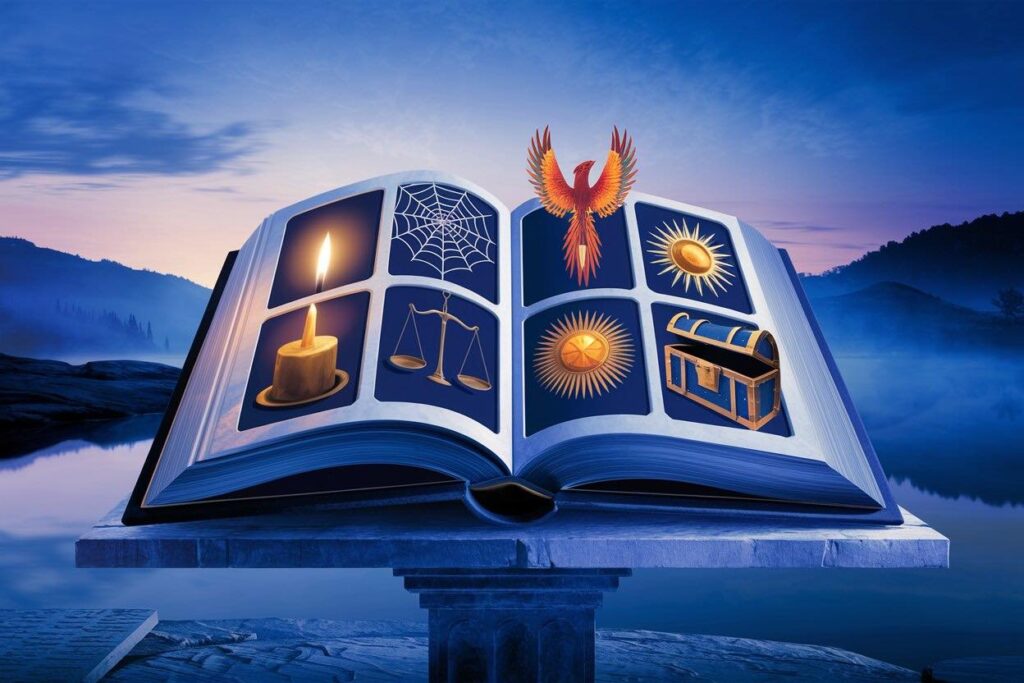

Universal or Archetypal Symbolism

This type draws from a shared reservoir of human experience. Certain symbols, such as water, fire, the sun, and the serpent, carry recognizable connotations across cultures and historical periods. Their power stems from this common inheritance. In literature, they provide immediate, foundational resonance. For instance, William Golding’s use of the conch shell in Lord of the Flies (1954) to signal order and civilized discourse leverages this universal recognition before the novel proceeds to dismantle it.

Contextual or Authorial Symbolism

Here, the symbol’s significance is generated entirely within the specific world of a single work. It carries no predetermined cultural association; the author builds its representational value through the narrative’s own internal logic. The green light in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925) or the glass menagerie in Tennessee Williams’s play The Glass Menagerie (1944) operate in this way. Their representational power is specific, elaborate, and inseparable from the text that created them.

Personal Symbolism

This category operates at the level of character psychology. An object or memory accrues intense, private importance for a specific figure within the story. Its power is subjective and may not be fully perceived by other characters or the reader. Miss Havisham’s preserved wedding feast in Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations (1861) operates with this subjective logic. It is a public display that encodes a private, traumatic history, representing a life arrested at a single catastrophic moment.

Functions of Symbolism

Symbolism serves specific technical purposes within a literary work. It is a strategic tool, not an ornamental addition.

Thematic Reinforcement and Complexity

Symbols provide a non-expository method for developing and complicating a work’s central ideas. A recurring symbol can trace the evolution of a theme by revealing its nuances through different contextual appearances. In Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter (1850), the embroidered ‘A’ is not a static emblem of shame. Its public perception shifts, and Hester Prynne’s relationship to it transforms. The symbol itself thereby charts the complex interaction among social condemnation, personal identity, and eventual, ambiguous reclamation.

Character Revelation

Symbols possess the capacity to externalize internal states and render psychology tangible. A character’s attachment to, interaction with, or repulsion by a symbolic object often reveals more than dialogue or action alone. The physical surroundings, such as a room or a possession, can become an objective correlative for a mental condition. The meticulous order of Sherlock Holmes’s apartment, for instance, mirrors the precise, catalogued structure of his deductive mind.

Atmospheric and Structural Cohesion

Symbols contribute to a work’s unity. A network of related symbols can establish a cohesive mood or tone, binding disparate narrative elements. They can also act as structural anchors by marking key transitions or echoing earlier moments which resonate across the text. The recurring fog in Dickens’s Bleak House (1853) operates in this way, by becoming both an atmospheric condition of London and a structural metaphor for the obfuscating nature of the legal case at the story’s center.

Economy of Expression

Finally, a potent symbol achieves a condensation of thought. It conveys a nexus of associations, historical echoes, or abstract concepts with the immediacy of a concrete image. This condensation bypasses discursive explanation. The writer communicates substantial conceptual material while maintaining the narrative’s immediacy and engaging the reader’s interpretative faculties.

Further Reading

The Lure of Literary Symbolism by Elizabeth Havey, Writer Unboxed

Do You See What I See: Symbolism in Literature by Beth Anne Freely Rauch, Medium

5 Important Ways to Use Symbolism in Your Story by Becca Puglisi, Writers Helping Writers

Symbolism and Imagery In Writing on Reddit