Explore This Topic

- Characterization in Literature: Types, Techniques, and Roles

- Character Arc: Transformative Journey in Fiction

- Character Development: Key Questions for Writers

- Character Analysis: Protagonists and Antagonists Explored

- Character Complexity in Literary Fiction

- Foil Character

- 10 Examples of Literary Archetypes

- Raskolnikov: A Character Analysis

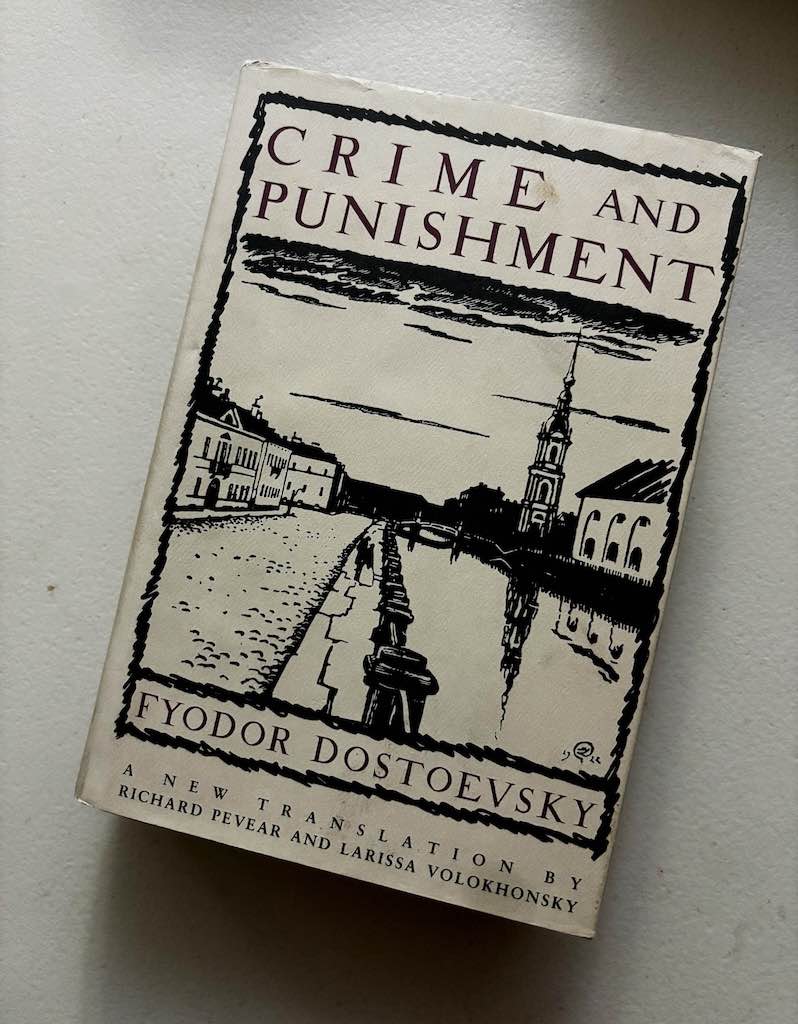

Rodion Raskolnikov, the protagonist of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment (1866), embodies a literary experiment. Dostoevsky constructs him to test a radical hypothesis: can a man, guided solely by a self-justifying intellectual theory, commit a profound transgression and maintain his psychological integrity? The novel serves as the meticulous record of this experiment’s failure, documenting the defeat of abstract ideology by the persistent forces of conscience and human connection.

This process of defeat defines the narrative’s structure and purpose. Raskolnikov’s journey from the conception of his “extraordinary man” theory to his final confession constitutes a rigorous inquiry into the limits of rationalization. To analyze him is to engage in essential character analysis, dissecting the precise mechanics by which a constructed intellectual identity breaks apart when confronted with an undeniable moral truth. The novel’s argument is that this moral truth forms a reality no theory can finally withstand.

The Experiment: Theory vs. Psyche

Raskolnikov’s intellectual isolation and material desperation form the required environment for his ideological test. The “extraordinary man” theory operates as the active agent of his character development, a premise that defines his actions to determine its viability.

He enacts this premise through the murder of the pawnbroker Alyona Ivanovna. The act is meant to affirm his conceptual superiority, but it produces the opposite effect. The theory fails immediately and completely. The mind it assumed would remain lucid and detached falls apart under the act’s visceral reality. Abstract justification cannot survive the tangible horror of violence, and Raskolnikov succumbs to a sickness that reveals a foundational conflict within himself.

This conflict generates the internal logic of his character arc. Each reaction that follows serves as new evidence against his original premise: the consuming paranoia before Porfiry, the conflicted attraction to Sonya, the relentless nightmares. The narrative traces how a rational theory comes apart when forced to acknowledge the specific human conscience it dismissed.

Narrative Mechanisms of Unraveling

Dostoevsky complements Raskolnikov’s internal monologue with a structured external system. The other characters operate with precision to expose and test the specific tensions within his constructed ideology. They function as active counterarguments, representing the vital human forces his theory rejects.

Sonya Marmeladova

As Raskolnikov’s definitive foil character, Sonya Marmeladova embodies a counterpoint to his entire philosophy. Her transgression, undertaken for the immediate survival of her family, highlights the abstract theoretical purpose of his own crime. In its aftermath, she embraces humility and accepts suffering without seeking a higher justification. The cross she offers functions as a simple, practical alternative: a way to establish identity through shared suffering. Through Sonya, Dostoevsky presents redemption as a difficult, actionable possibility.

Porfiry Petrovich

Porfiry Petrovich operates as the narrative’s mechanism of psychological accountability. His method employs strategic indirectness and Socratic dialogue, systematically dismantling Raskolnikov’s intellectual justifications from within. Porfiry constructs conversations that force Raskolnikov to confront the logical flaws and emotional truth of his own position. In this role, he externalizes Raskolnikov’s suppressed conscience, transforming a private moral conflict into a sustained, inescapable fact. Porfiry’s interrogations render the abstract failure of the “extraordinary man” theory concrete and immediate.

Svidrigailov

Svidrigailov actualizes the final state of Raskolnikov’s theory. He serves as a dark archetype, presenting the “extraordinary man” ideal reduced to its core of cynical boredom and moral negation. His actions and final fate demonstrate the terminal result of a philosophy that denies conscience: an existential void that demands self-annihilation. Svidrigailov’s explicit presence defines the stakes of Raskolnikov’s internal conflict, making the alternative embodied by Sonya not one of preference but of vital necessity.

The Verdict: Suffering as Reconstitution

Raskolnikov’s Siberian sentence is the formal, legal confirmation of a psychological truth he has already enacted. His conscious suffering merges his physical punishment with the psychological guilt Porfiry methodically exposed and the nihilistic alternative Svidrigailov ultimately chose. The sentence does not create a new condition; it acknowledges the one that already exists.

The failure of the “extraordinary man” theory lies in its false premise: that a consciousness could remain detached from the moral reality of its actions. Sonya embodies the counter-premise: that identity is built through responsibility to others. Raskolnikov’s path forward, therefore, is not theoretical but practical. It begins with the confession, which is the first active step in constructing a self according to this different, more tenable principle. This arduous, practical labor—the slow replacement of one foundational self-conception with another—is the ultimate demonstration of his character complexity.

Thus, Raskolnikov endures not as a model of the exceptional individual, but as proof of its impossibility. His entire trajectory—from the conception of his theory to its empirical failure and his subsequent struggle toward a new self—serves as Dostoevsky’s definitive argument. It asserts that the human psyche cannot be partitioned; the intellectual self cannot commit an act from which the moral self will remain detached. The novel’s power lies in its relentless documentation of this truth, making Raskolnikov’s story a permanent examination of the indivisible link between thought, action, and identity.

Selected Passage with Analysis

I was not bowing to you, I was bowing to all human suffering.

Page 322, Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky, trans. by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky

In this pivotal line, Dostoevsky encapsulates the novel’s exploration of guilt, redemption, and the shared burden of human suffering. Spoken by Raskolnikov, this statement represents a moment of profound self-awareness. His refusal to bow to any one individual signifies his rejection of hierarchical morality, aligning instead with the universal human condition.

The line reveals Raskolnikov’s internal struggle as he grapples with the ramifications of his crime. By bowing to human suffering, he acknowledges a commonality that binds all people, challenging his earlier embrace of utilitarian ethics, which justified the murder of the pawnbroker. This admission underscores his growing recognition that suffering, rather than power or intellect, is the true path to spiritual reconciliation.

Dostoevsky’s Christian existentialism is central here: Raskolnikov's bow reflects a nascent humility and acceptance of his humanity, marking the beginning of his moral and spiritual rebirth. It aligns with the novel’s broader theme of redemption through suffering, which Dostoevsky presents as a means of transcending individual guilt to attain grace. Ultimately, the statement serves as a profound critique of alienation, highlighting the redemptive power of empathy and the necessity of confronting shared human anguish to achieve salvation.

Further Reading

Why should you read “Crime and Punishment”? by Alex Gendler, TED-Ed

The Lockdown Lessons of “Crime and Punishment” by David Denby, The New Yorker

What’s the philosophy behind Fyodor Dostoevsky’s crime and punishment? on Quora

Can anyone else relate to Raskolnikov? on Reddit