Explore This Topic

Narrative perspective dictates the temporal progression of a story, the disclosure of information, and the audience’s proximity to its characters. This vantage point establishes what remains knowable and the timing of its revelation. It calibrates the impact of each event. Perspective sets the foundational conditions for a narrative long before plot or theme emerges.

A focus on perspective refines the craft of writing and the act of reading. For writers, it reveals how regulating distance and access can intensify narrative tension or enrich characterization. For readers, it exposes the subtle structural mechanics that guide interpretation, particularly when a story alters its focus or restricts its field of vision. Identifying these mechanics creates the necessary foundation for analyzing how specific narrative methods function.

Definition: Point of View

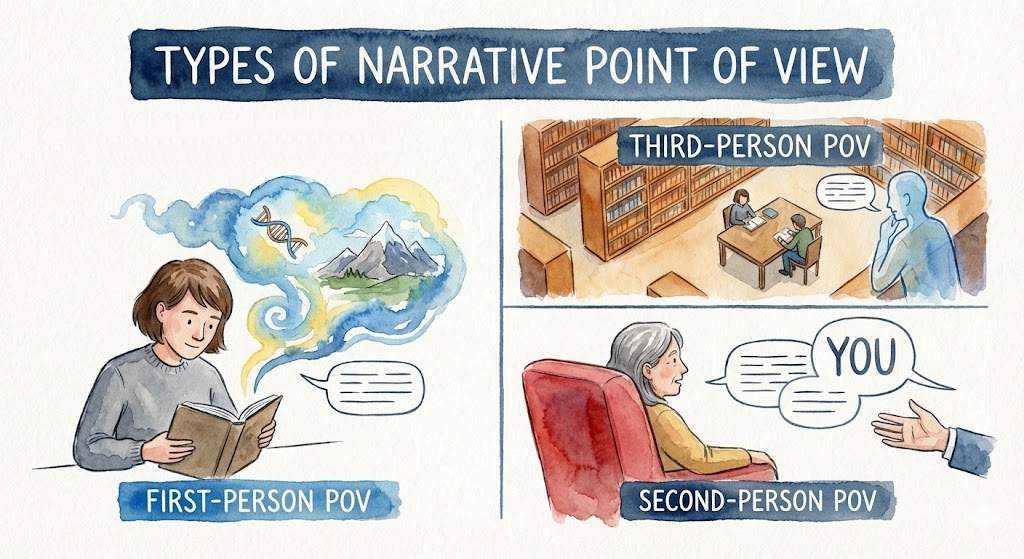

Point of view (POV) denotes the narrative lens through which events are filtered and relayed. It defines the informational boundaries presented to the audience and colors their interpretation of the action and the actors. By fixing a specific POV, an author controls the reader’s proximity to and alignment with the unfolding plot. This foundational choice unlocks a spectrum of narrative potential. Each of the primary forms (first person, second person, and third person) fulfills a unique function in the architecture of a story.

Types of Narrative Point of View

Whether written in first, second, or third person, each narrative POV opens a distinct path for creative expression. Writers who grasp these perspectives gain greater control over how their stories unfold and use them to construct textured plots and multidimensional characters without falling into predictable patterns. At the same time, the thoughtful use of narrative POVs enhances reader engagement, deepens their connection to characters and events, and presents stories through diverse perspectives.

First-Person Point of View

First-person narrative creates a direct link to the narrator’s mind by pulling the audience into a close encounter with the character’s thoughts, emotions, and private logic. This perspective moves through the protagonist’s experiences as they happen, with each moment filtered through personal triumphs, internal struggles, and a singular, subjective worldview. By offering a firsthand view of events, it stimulates a sense of immediacy and personal investment. However, it also confines the narrative to the narrator’s understanding, which may distort the truth, overlook important details, or misinterpret others’ motives.

Writers must balance introspection with action to prevent the story from becoming overly self-focused. For example, while the narrator’s voice can enhance authenticity, excessive internal monologues may slow the narrative’s pace. Successful first-person perspective combines personal reflection with external engagement to maintain narrative momentum and complexity.

Characteristics:

- Intimate and personal perspective

- Limited to the narrator’s knowledge and experiences

- The narrator is a character in the story, using “I” or “we”

Variations:

| Definition | Examples | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Unreliable Narrator | ||

| Narrator provides a skewed, biased, or inaccurate account of events | The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger, Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn | Encourages readers to question the narrative and interpret events critically |

| Stream of Consciousness | ||

| Thoughts and feelings emerge in unfiltered succession, in a manner that reflects the mind’s natural rhythm | Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf, Ulysses by James Joyce | Creates intimacy by immersing readers in the character’s thought process |

| First-Person Plural | ||

| Uses “we” instead of “I,” to present a collective perspective | The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides, Then We Came to the End by Joshua Ferris | Gives voice to a group and highlights shared experiences and a sense of collective memory |

| Retrospective Narration | ||

| Narrator reflects on past events with hindsight | To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, Great Expectations by Charles Dickens | Adds depth, as the narrator’s perspective may change over time |

| Epistolary First Person | ||

| Story unfolds through letters, diary entries, or personal documents | Dracula by Bram Stoker, The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky | Adds intimacy and immediacy, as if the narrator is confiding directly in the reader |

| Framed First Person | ||

| Narrator introduces a story involving other characters’ stories or an embedded narrative | Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad, Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë | Creates a layered storytelling experience by presenting distinct viewpoints |

| Confessional Narration | ||

| Narrator confesses actions, thoughts, or feelings, often with guilt or reflection | Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov, “The Tell-Tale Heart” by Edgar Allan Poe | Generates tension and insight into the narrator’s psyche |

| Limited First Person | ||

| Narrator possesses limited knowledge, confined to what is directly observed, felt, or experienced in the moment | Room by Emma Donoghue, Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes | Amplifies emotional impact through a confined perspective |

While this overview establishes the core types and functions of first-person narration, a dedicated analysis examines its dual nature as a craft challenge and a psychological contract. Our focused article, First-Person Point of View, explores the construction of narrative voice, the strategic management of its limitations, and the complex dynamics of reliability and trust between narrator and reader.

Second-Person Point of View

Second-person narrative directly engages the audience by addressing them as “you” and placing them in the protagonist’s role. This perspective creates a unique sense of immersion as readers experience events from within the story. Though seldom employed in long-form fiction because of its structural demands, it thrives in experimental works and short stories. It offers a distinctive method to convey sensation and emotion through an unconventional perspective.

This POV often erases the distance between reader and character by establishing the tone to feel inward-looking and contemplative. However, sustaining second-person narrative can be demanding, as it requires careful crafting to avoid alienating the audience. When used effectively, it transforms the narrative into a deeply personal experience.

Characteristics:

- Immersive and often experimental

- Common in instructional texts or innovative literary works

- The narrator addresses the reader or a character directly, using “you”

Variations:

| Definition | Examples | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Address to the Reader | ||

| Narrator speaks directly to the reader as if they are the protagonist or participant | Choose Your Own Adventure books, instructional texts | Engages the reader actively, making them feel immersed in the story or directly involved |

| Hypothetical or Generalized “You” | ||

| The narrator uses “you” in a generalized, hypothetical manner to represent an unspecified individual | Reflective essays or universal musings | Encourages relatability by addressing universal situations or shared human experiences |

| Character-to-Character Address | ||

| One character directly addresses another within the story, referring to them as “you” | Monologues, letters in epistolary fiction | Adds intimacy and emotional weight, as it feels like a direct dialogue or personal conversation |

| Unreliable Second-Person Narrative | ||

| The narrator manipulates the “you” perspective, which creates ambiguity or misinterpretation | Experimental or postmodern works | Creates a surreal or destabilizing tone that challenges the reader’s trust in the narration |

| Split Perspective in Second Person | ||

| The “you” alternates between addressing the reader and referring to a character in the story | Experimental or dual-layered narratives | Blurs the line between audience and participant that adds complexity and multiple layers of meaning |

Second-person narrative is relatively rare in fiction, particularly in novels or long-form works, which limits the exploration of its variations compared to first- or third-person perspectives. Additionally, the standard use of “you” as direct address carries a distinct, specific tone—its clarity and directness give it a strong structural presence that rarely calls for deviation. As a result, second-person narrative often retains its core features across most works, with only occasional experimentation to push its boundaries.

This direct address stands in stark contrast to the observational distance of third-person or the internal focus of first-person narration. For a complete examination of when and why an author chooses this demanding perspective, including its notable successes in modern fiction, see our dedicated article Second-Person Point of View.

Third-Person Point of View

Third-person narrative is one of the most versatile and widely used narrative perspectives in literature, where the narrator exists outside the story and refers to characters using pronouns like “he,” “she,” “they,” or their names. This perspective offers flexibility in storytelling, ranging from the all-knowing insights of third-person omniscient to the focused lens of third-person limited, which centers on a single character’s internal experiences.

Another approach, third-person objective, takes a neutral stance and presents only observable actions and dialogue without entering any of the character’s thoughts or feelings. Each subcategory has distinct strengths and drawbacks, which makes third-person narrative a powerful tool for defining the scope and focus of a story.

Third-Person Omniscient

Third-person omniscient POV offers a wide-ranging vantage point that includes the inner lives of multiple characters. Authors can trace overlapping motivations and reveal how relationships evolve across the narrative. With this expanded scope, the structure supports deeper thematic investigation and a more dynamic portrayal of events.

While offering flexibility, omniscient narration requires careful handling to avoid overwhelming the audience. Effective use of this perspective requires careful management of focus and voice. The narrative must maintain coherence while moving between characters, with each shift adding dimension and contributing meaningfully to the story’s structure.

Characteristics:

- Provides a godlike perspective, unrestricted by time or space

- Can move freely between characters’ minds and different scenes

- Offers insights into the motives, emotions, and backgrounds of all characters

- Risks overwhelming the reader if transitions between viewpoints are not seamless

Examples:

- George Eliot’s Middlemarch (1871) uses an omniscient narrator to navigate the interwoven lives of its characters, which gives the narrative broader reach and intricacy.

- Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1867) uses this perspective to portray a wide range of characters and events, capturing the complexity of human relationships and historical change.

For a complete, dedicated analysis of this powerful perspective, see our comprehensive article Third-Person Omniscient Point of View.

Third-Person Limited

Third-person limited POV centers the narrative on one character’s inner world while maintaining enough distance to depict events beyond that character’s immediate perception. Writers can examine the nuances of a character’s thoughts and emotions without relinquishing the broader control of the story’s direction. By combining subjective and objective elements, third-person limited provides both emotional depth and narrative versatility.

This perspective avoids the pitfalls of first-person introspection by maintaining a degree of narrative distance. It gives authors the flexibility to redirect attention within the narrative, so they can develop characters in greater detail and guide the plot with deliberate precision. However, the limited scope may restrict the audience’s understanding of events outside the chosen character’s perspective.

Characteristics:

- Deeply personal, offering an intimate view of one character’s thoughts and emotions

- Limited to what the focal character knows, sees, and experiences

- Avoids “head hopping” by maintaining a consistent narrative focus,

- Adds suspense or mystery by withholding information outside the character’s knowledge

Examples:

- In Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (1813), the third-person limited perspective follows Elizabeth Bennet closely and brings her judgments and reactions to the forefront as the story progresses through her interpretive lens.

- In Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go (2005), the narration remains closely tethered to Kathy H., as her private recollections and emotional undercurrents unfold through the lens of memory.

Third-Person Objective

Objective narration depicts events without probing into characters’ internal thoughts or emotions, presenting the story as an impartial observer. This perspective relies on dialogue, actions, and descriptions, challenging the audience to interpret events and motivations independently. By withholding subjective insight, it promotes an active engagement with the narrative.

Its emphasis rests on external detail. This generates a quality of realism and present-moment intensity. However, the inherent detachment can constrain emotional engagement with characters. This renders the mode particularly suited for narratives where ambiguity and interpretive space are fundamental.

Characteristics:

- No access to internal thoughts or feelings

- Impartial and detached tone

- The narrator remains neutral, presenting only observable actions and dialogue

Examples:

- Ernest Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants” (1927) illustrates objective narration through its reliance on dialogue and subtle cues to convey the story’s tension.

- Raymond Carver’s short stories, such as “Cathedral” (1983), often use objective narration to explore the nuances of human interaction and perception.

Comparison of Subcategories in Third-Person Point of View

The subcategories of third-person narrative (omniscient, limited, and objective) differ significantly in their scope and focus. Each of them offers a unique approach to narrative construction. Here’s a table comparing the subcategories of third-person POV:

| Subcategory | Key Features (Scope & Focus) | Primary Effect (Strengths & Challenges) |

|---|---|---|

| Third-Person Omniscient | Broadest scope with access to all characters’ thoughts, feelings, and motivations across multiple events and locations. | Creates expansive, multifaceted narratives ideal for complex plots and character dynamics, though it risks overwhelming the narrative if without seamless transitions. |

| Third-Person Limited | Scope limited to the internal experiences of one focal character at a time, offering a personal and intimate portrayal. | Balances deep character insight with cohesive storytelling for character-driven works, though it restricts the reader’s perspective to the character’s knowledge. |

| Third-Person Objective | Presents only observable actions and dialogue without revealing any internal thoughts or feelings, creating a neutral, external view. | Encourages independent reader interpretation and creates a detached tone, though it requires actions and dialogue to expertly convey meaning without internal insight. |

The grammatical point of view is just one lens for understanding a narrative voice. To gain a complete picture, we must also consider other critical dimensions like the scope of knowledge and relationship to the truth. Together, these elements form the essential framework outlined in our guide to the Types of Narration.

Further Reading

Once Upon a Time, There Was a Person Who Said, ‘Once Upon a Time’ by Steve Almond, The New York Times

Observers, Bystanders, and Hangers On: Ten Novels with Unlikely Narrators by Juliet Grames, The Millions

Multiple Narrators, Multiple Truths: A Reading List by Sophie Ward, Literary Hub

12 Books That Break the Rules of Point of View by Sophie Stein, Electric Literature