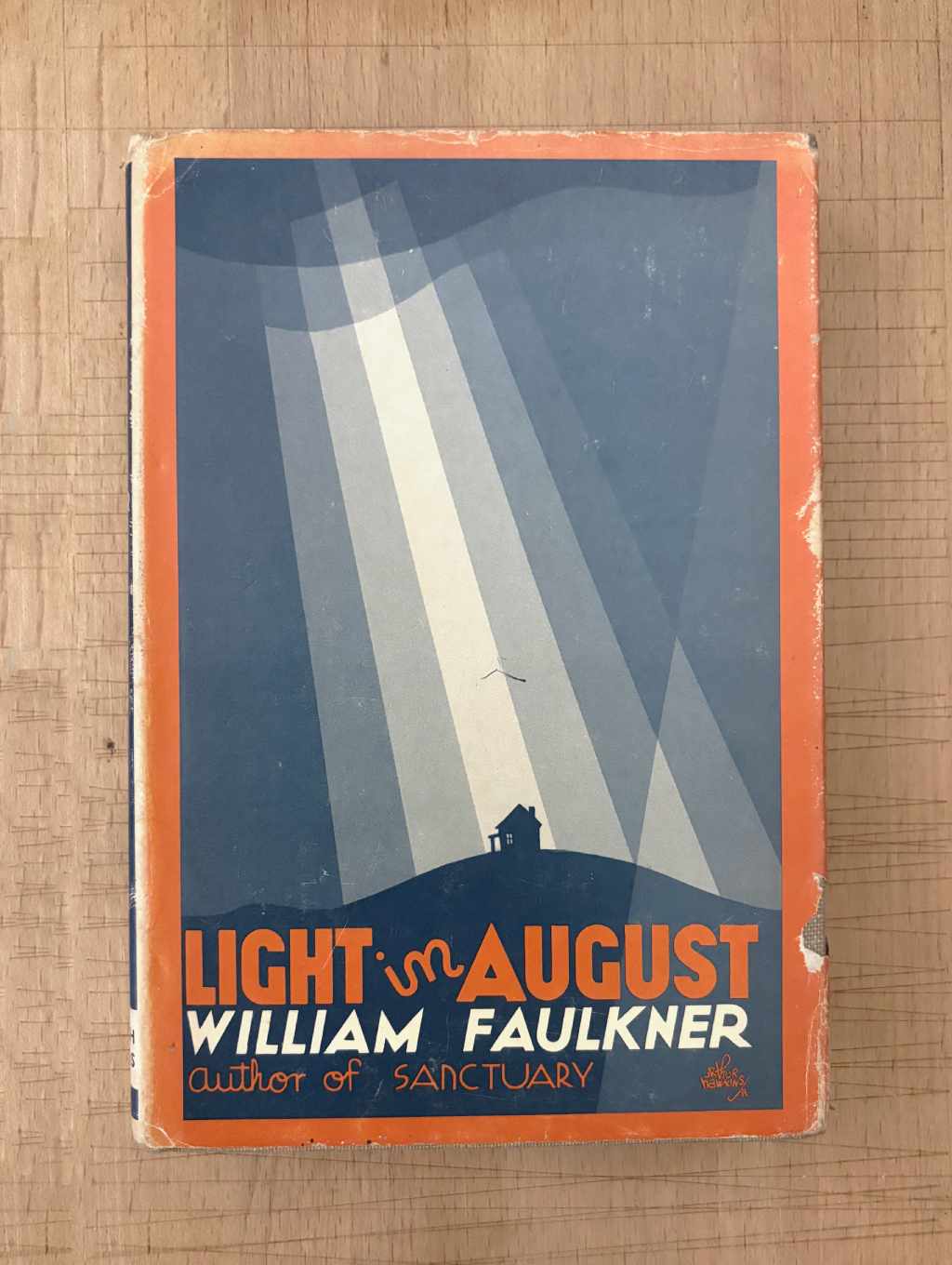

William Faulkner’s Light in August (1932) imposes severe requirements on its reader. It eschews easy answers and tests the limits of emotional and philosophical tolerance. Beyond typical Southern Gothic, the novel shows the conflicts of race and violence in the American South without attempting to conclude them. It is built on the inescapable influence of ancestry—biological, regional, and spiritual—and its characters exist in a world where history has already set the course of their lives.

Faulkner avoids a single, unified plot, composing the narrative from multiple, diverging threads. The story begins with a pregnant woman named Lena Grove walking alone toward Jefferson, Mississippi, and ends in blood and disappearance. In between lies a shifting arrangement of lives: Joe Christmas, whose uncertain racial heritage fuels his self-destruction; Joanna Burden, ostracized for her ancestry and ideals; Reverend Hightower, haunted by his family’s mythic past; and Byron Bunch, whose earnestness seems powerless in the face of collective delusion.

Faulkner’s Narrative Design

Faulkner breaks the standard chronology on purpose. The story jumps freely through time and revisits the same events using different characters’ perspectives. This rejection of simple, linear storytelling is a narrative device: by preventing any sense of certainty, it forces the reader to confront how rumor and prejudice change the past into something else entirely.

This structural disordering mirrors the psychological state of the main characters. Joe Christmas, whose own identity has been distorted by years of abuse and isolation, occupies a narrative space that is likewise disjointed. His story is filtered through the voices of others, most of whom do not fully understand him, and perhaps cannot. The result is a portrait of a man who exists as myth before he is known as a person.

In sharp contrast, Lena Grove’s chapters suggest a simple, almost fable-like rhythm. Her presence acts as a stabilizing current in the novel’s flow. She is never given the same detailed psychological scrutiny as Joe or Hightower, yet her journey becomes the only movement that advances the story. Where others remain trapped in memory and obsession, she moves steadily forward.

Language and Style

Faulkner’s prose in Light in August veers between the lyric and the opaque. At moments, it achieves a rare eloquence, particularly when rendering interior monologue. But it also courts excess. When sentences extend far beyond their grammatical center, clarity becomes secondary to rhythm. This stylistic volatility suits a novel so concerned with instability. What Faulkner asks is not for the reader to follow the story, but to submit to the language.

His sentences often mimic thought rather than speech, which pulls the reader directly into a character’s mind. This technique creates a density that can frustrate, but it also reveals. When Joe Christmas turns inward, the language becomes jagged and recursive. When Reverend Hightower recalls the spectral image of his grandfather’s Civil War death, the prose circles around his memories. The form is dictated by the mind behind it.

There is a noticeable difference between what characters think and what they say. Spoken conversations (dialogue) are often short, awkward, or even stiff. This shows that the characters’ actual words are too insignificant to carry the heavy feelings and tragic pasts they inherited. This failure of simple language to express deep experience is a central theme of the novel.

Characterization and Identity

Faulkner’s approach to characterization is subtractive, not additive. His characters do not develop gradually but are introduced as fully formed, yet burdened by past events and lineages that define them, even before the reader knows their names.

Joe Christmas

Joe Christmas is presented immediately as a dysfunctional figure. Taken from an orphanage and raised under rigid religious discipline, he grows into a man incapable of trust or intimacy. He carries the suspicion that he is of mixed race, and this unprovable identity becomes the center of his self-loathing. That possibility becomes his burden, even his doom, long before the townspeople use it as justification for his self-destruction.

Christmas exists in a state of permanent alienation, drifting through social and racial identities without belonging to any of them. Too ambiguous for any group to fully claim, his rage is not superficial but ingrained, an expression of the confusion and violence imposed upon him since childhood.

Joanna Burden

Joanna Burden’s life, too, is decided by her lineage. Her family’s strong abolitionist history marks her as an outsider in Jefferson, compelling her into near-total seclusion. The town tolerates her only because her presence is marginal; she is viewed as a remnant of an external ideology that Jefferson has long ago rejected.

Her relationship with Joe Christmas is fraught from the beginning. What starts as physical attraction soon takes on a punitive and coercive dynamic. Joanna projects onto Joe both her ancestral guilt and her desperate need for spiritual absolution. Her intense religious zeal becomes a kind of possession, displacing intimacy with rituals of self-negation. Her final actions—a sequence of seduction, prayer, and sacrifice—reveal the absolute internalization of the conflict between her belief and her desire.

Reverend Hightower

Reverend Hightower is the only character who seems to exist entirely in the past. Though physically present in Jefferson, his mind is tethered to an imagined lineage of heroism, one that is centered on his grandfather’s Civil War death, which he has mythologized into a form of faith. His retreat from community, responsibility, and even from narrative logic reflects a kind of spiritual paralysis.

He ceases to actively minister, becoming a witness who refuses to intervene. His failure to act—particularly concerning the fate of Joe Christmas—is not simply an act of cowardice, but the logical conclusion of a life entirely consumed by fantasy. Hightower chose reverence for the dead over accountability to the living. In the end, the clarity he gains arrives too late, rendering his epiphanies empty of consequence.

Symbolism and Recurring Motifs

The novel’s symbolic framework is rooted in Christian allegory, Southern mythology, and the pervasive language of race. Joe Christmas’s initials, his birth on Christmas Day, and his eventual death at the hands of a violent mob all suggest a dark inversion of martyrdom. But Faulkner offers no resurrection. The symbolism exposes the brutality of projecting divinity onto a man whose humanity has been denied from every side.

Fire is a recurring motif in the novel, most vividly seen in the destruction of the Burden house. Its function is dual: it serves as a ritualistic purification and erasure, and simultaneously removes the evidence of social transgression. In Faulkner’s South, fire acts as a social solvent; the community uses it to eliminate that which defies comprehension, ensuring that what cannot be explained must be burned.

Lena Grove’s pregnancy also holds symbolic significance. Unlike the others, her role is not based on abstract ideas; her journey is not described with philosophical breadth. Nevertheless, her presence introduces a low-key challenge to the patterns of violence and inactivity that grip the other characters. She walks forward while others are trapped in memory. Her child, unnamed and unseen for most of the novel, becomes the only suggestion of continuity in a story otherwise filled with structural gaps.

The Role of Place

Jefferson, Mississippi, is more than a backdrop; it operates as an active agent of judgment and containment. The town does not passively receive events but actively distorts them and enacts consequences. Its citizens do not require facts; rumor suffices for justice. Legal process is secondary to communal judgment.

The novel’s geography reinforces its social hierarchies. Joanna Burden’s home sits isolated from the main community. Hightower resides above the street, in a room that turns away from the world. Joe Christmas travels constantly, never truly belonging inside or outside the town. Only Lena possesses mobility, and it is this freedom of movement that distinguishes her, potentially offering a redemptive contrast.

The houses, churches, and stores are not just settings but vessels of memory and ideology. They influence events rather than simply contain them. Because the town’s physical space is never neutral, its people cannot be either. The destiny of each character is defined by the specific place that both identifies and restricts them.

Conclusion

Light in August secures its status as a definitive Southern text because it withholds easy insights and holds conclusion at a distance. Its enduring role is the capacity to sustain complexity. The demanding prose and structural difficulty compel the reader to confront the novel’s central paradox: the conflicts of race and violence are so deeply rooted in the land and ancestry that they have no final answer.

Faulkner’s work stands as a devastating portrait of inherited guilt, showing how society denies humanity to those it cannot classify or categorize. What remains after reading is a state of permanent severance. The novel is defined by the continued, steady forward movement of Lena Grove contrasted with the tragic stasis of lives consumed by the past, and its dense prose forces the reader to sit with that contrast rather than resolve it. Light in August is, in the end, a profound meditation on the terrifying power of history to write a person’s destiny in advance.

Further Reading

Light in August on Wikipedia

Critical Essays: The Individual and the Community in Light in August by CliffsNotes

Light in August: Study Guide by SparkNotes

“Light in August” Discussion on Reddit