Hyperbaton is a literary device that alters the normal order of words in a sentence to achieve emphasis, rhythm, or a heightened effect. The term derives from the Greek for “overstepping,” and it has been used for centuries by poets, dramatists, and novelists to alter expected syntax. By rearranging words in unconventional ways, writers create a linguistic tension that draws attention to the sentence and amplifies its expressive power.

How Hyperbaton Works in Syntax

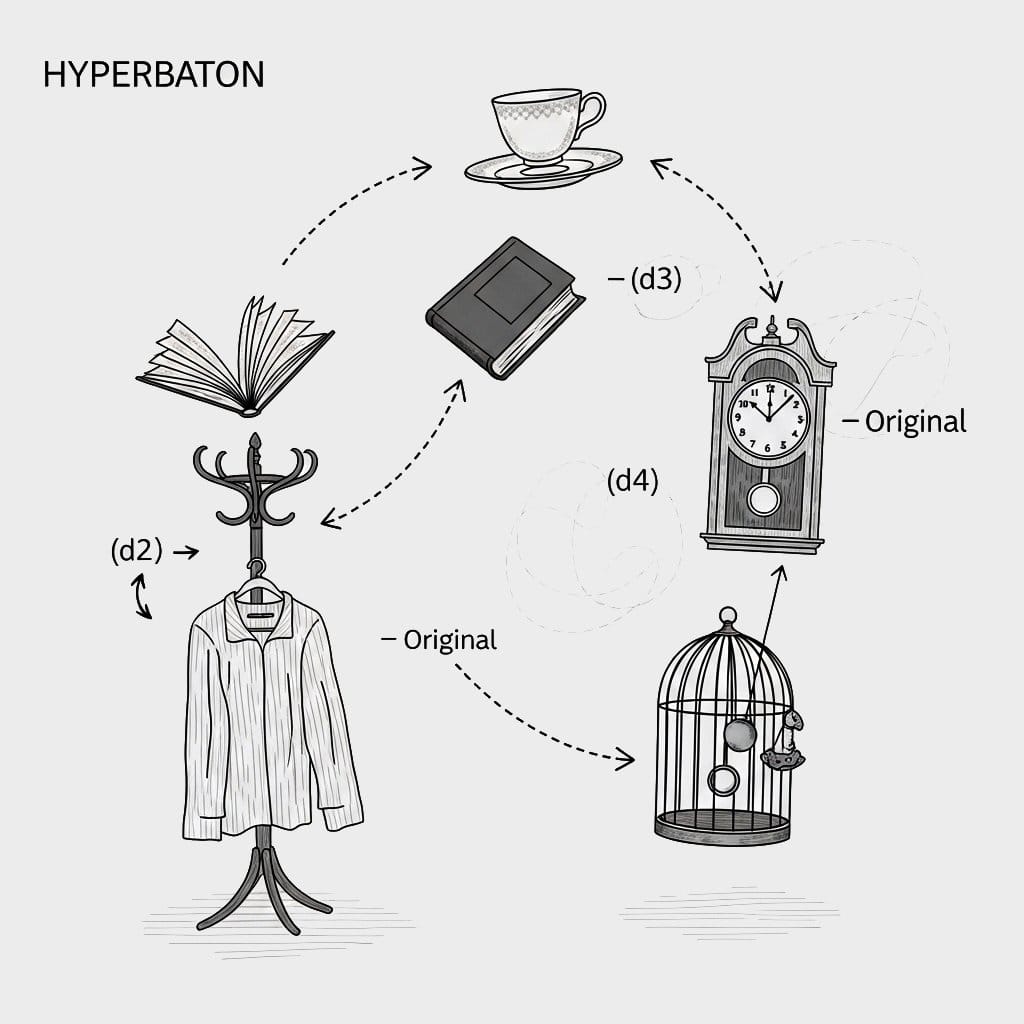

Hyperbaton occurs when the standard subject-verb-object sequence in English is inverted. Writers may move the object to the front of the sentence, place adjectives after nouns, or scatter clauses across unusual positions. These shifts highlight particular words or ideas while creating rhythm.

John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667) demonstrates this technique: “Of Man’s first disobedience, and the fruit / Of that forbidden tree.” Here, the object comes before the verb, foregrounding “disobedience” as the central concern of the epic.

Hyperbaton differs from anastrophe, which also involves inversion, but usually on a smaller scale such as flipping adjective and noun order, as in “the forest primeval.” Hyperbaton often encompasses larger inversions, extending across phrases or clauses.

Hyperbaton in Classical Rhetoric

Origins in Greek and Latin

Ancient rhetoricians recognized hyperbaton as a mark of elevated style. Greek tragedies and Latin epics frequently employed it. In Virgil’s Aeneid (29–19 BCE), lines such as “Litora multum ille et terris iactatus et alto” (“That man, buffeted much on land and sea”) scatter words across clauses to echo the wandering subject matter.

Rhetoricians across antiquity recognized hyperbaton as a deliberate rhetorical strategy, not merely a byproduct of Latin’s flexible word order. Later educational works—including Rhetorica ad Herennium—define it as the figure “which disturbs the order of words.”

Influence on Later Literature

The rhetorical training of the Renaissance revived hyperbaton in English, French, and Italian verse. Poets such as Edmund Spenser and Torquato Tasso adapted the device to recreate the grandeur of classical epic. Hyperbaton became synonymous with heightened diction.

Hyperbaton in Poetry

Creating Rhythm and Musicality

Poets use hyperbaton to mold rhythm. William Shakespeare, in Sonnet 20, writes: “A man in hue, all hues in his controlling.” The unexpected placement of “controlling” at the end shifts stress and creates a melodic cadence.

Intensifying Imagery

Emily Dickinson, known for her syntactic strangeness, frequently used hyperbaton. In “Because I could not stop for Death” (1890), she writes: “We slowly drove – He knew no haste.” The reversal foregrounds the slowness of the drive, reinforcing the calm inevitability of death.

Hyperbaton in Prose

Shaping Character Voice

Novelists employ hyperbaton to give speech patterns a distinctive edge. In William Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom! (1936), sentence structures twist and loop, sometimes abandoning conventional syntax. This technique mirrors the disjointed storytelling of the narrators and heightens the novel’s intensity.

Elevating Descriptive Passages

Charles Dickens occasionally inserted hyperbaton for dramatic emphasis. In A Tale of Two Cities (1859), the famous line “A far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known” bends normal word order to intensify its solemnity.

Hyperbaton vs. Other Figures of Speech

Hyperbaton and Anastrophe

Anastrophe is a narrow form of inversion, often limited to swapping word pairs, such as “dark side” becoming “side dark.” Hyperbaton operates on a larger scale, sometimes reorganizing entire clauses.

Hyperbaton and Parenthesis

While hyperbaton reorders words, parenthesis inserts additional words or clauses into a sentence. Both interrupt normal flow, yet parenthesis adds rather than rearranges.

The Function of Hyperbaton

- Emphasis and focus: By displacing expected order, hyperbaton shines a spotlight on chosen words. Milton’s opening object “Of Man’s first disobedience” establishes disobedience as the center of the epic.

- Tone and style: Hyperbaton conveys grandeur, solemnity, or strangeness. The deviation itself becomes expressive, imbuing the text with a heightened quality that straightforward syntax cannot achieve.

- Mimicking thought and emotion: Writers often use hyperbaton to mirror how thoughts emerge in bursts or how passion overrides grammatical order. This gives speech a spontaneous quality that mimics natural yet heightened expression.

Why Hyperbaton Matters

Hyperbaton matters because it demonstrates how syntax can function as an artistic instrument rather than a neutral vessel for expression. By shifting words out of their expected places, writers bend grammar into a device of emphasis, rhythm, and intensity. The shift draws attention to arrangement as much as to content. It turns structure into a conscious design.

The device also reveals how literature can echo states of thought and feeling through departures from ordinary syntax. In moments of passion, grief, or ecstasy, speech often slips into irregular or reassembled forms. Hyperbaton captures this spontaneity while maintaining a crafted design.

When Milton reorders clauses in Paradise Lost or Dickinson shifts the placement of verbs and adjectives, the very structure of the sentence becomes central to the artistry. This heightens solemnity, strangeness, or lyrical cadence. Hyperbaton shows that language is never fixed. Its order is malleable and can produce powerful effects through placement alone.

Further Reading

What is Hyperbaton? by J.W. Carey, Vers Libre

Hyperbaton on Wikipedia

[The Elements of Eloquence] How to use Hyperbaton to make your prose pretty. on Reddit