Descriptive writing is the art of perceptual transcription, a translation of the sensory world into language. Its purpose is simulation, that meticulous construction of a palpable reality within the reader’s consciousness. This craft demands a writer’s highest discernment: the selection of which dimensions to render, which senses to engage, which words to bear the precise detail of the observed moment. True mastery resides in the particular, by leaving behind the vague “beautiful” for the exact quality of afternoon light filtering through dust, or the specific, hollow report of a footstep in an empty hall.

What is Descriptive Writing?

Descriptive writing functions as a literary mode of expression dedicated to the vivid portrayal of its subject. It seeks to reproduce the sensory and impressionistic data of a scene, character, or object through the strategic application of language. Its objective is immediacy. Consider the difference between simply stating a city’s environment and detailing the “neon signs of Tokyo, their electric glow bleeding into rain-slick sidewalks to create a constellation of shattered light.” The latter formulation does not just inform; it constructs an experience by leveraging specific, concrete details that generate a mental image with texture and atmosphere.

Why Descriptive Writing Matters

Descriptive writing matters because it performs a fundamental act of conversion. It transmutes the inert data of a narrative into sensory and emotional fact. A simple statement of weather becomes, in skilled hands, the “playful fingers of a breeze weaving through tall grass.” This alchemy changes the reader’s position from a distant auditor to a situated witness within the scene.

This mode of writing provides the primary texture of fiction and the persuasive color of nonfiction. In travel writing or nature essays, it transmits the essence of a place, e.g., the chill of mountain air or the cacophony of a foreign market, directly to the senses. It functions as the binding agent of atmosphere, fixing the reader’s attention by making the abstract concrete, the general specific, and the reported event a physical occurrence.

Principles of Descriptive Writing

Effective descriptive prose adheres to a set of disciplined principles. These are not just decorative suggestions but technical requirements for clarity and impact.

- Precision and economy: Every word must justify its place. Description thrives on the exact noun, the potent verb, or the revealing adjective. Superfluous embellishment obscures the subject; precision reveals it. The goal is to isolate the defining characteristic (the gnarled twist of a branch, the brittle dryness of autumn leaves) and not to catalogue every visible detail.

- Sensory specification: Abstraction is the enemy. Writing must engage the specific channels of perception: the cobalt blue of a twilight sky, the grating scrape of a chair on stone, and the damp, fungal scent of a cellar. These details build a composite sensory reality. The writer chooses which senses to activate in order to construct the intended impression.

- Narrative subordination: Description exists in service to a larger purpose—character, mood, or plot. It must never become a self-indulgent digression. Its length, intensity, and focus are dictated by the narrative’s immediate needs. A description that halts momentum fails its primary function.

- Originality of perception: Language must avoid the well-worn path. Clichés and habitual phrases (“crystal clear water,” “deafening silence”) have lost their descriptive power through overuse. The writer’s task is to see the subject anew and identify a fresh linguistic counterpart for that perception.

Common Pitfalls in Descriptive Writing

Descriptive writing can falter when it becomes overly elaborate or lacks focus. These errors arise from a misunderstanding of the craft’s purpose, substituting accumulation for precision and ornament for function.

- Overuse of flowery language: A common failure is the belief that more elaborate language creates better description. This leads to prose saturated with florid adjectives and metaphors that draw attention to the writer’s effort, not the subject. The result is obscurity with purple prose. Effective description seeks clarity through the exact word, not overdecoration through a surplus of words.

- Lack of sensory details: A second error is presentation without sensation. Writers may list visual facts, e.g., the table’s dimensions and the wall’s color, while omitting the texture of the wood, the room’s acoustic quality, or the scent of old paper. This creates a schematic, disembodied setting. Description requires the strategic activation of the senses to construct a believable physical space.

- Redundancy: Weak description often circles a single idea, rephrasing it without advancing the perception. A character described as “tired, weary, and fatigued” gains no dimension. Each sentence must introduce new information: a shift in sensory focus, a revealing detail, or a deepening of the initial impression. Redundancy signals a depleted vocabulary or a failure to observe the subject with sufficient rigor.

By prioritizing precision and keeping descriptions aligned with the story’s purpose, writers can avoid these pitfalls and create impactful, memorable work.

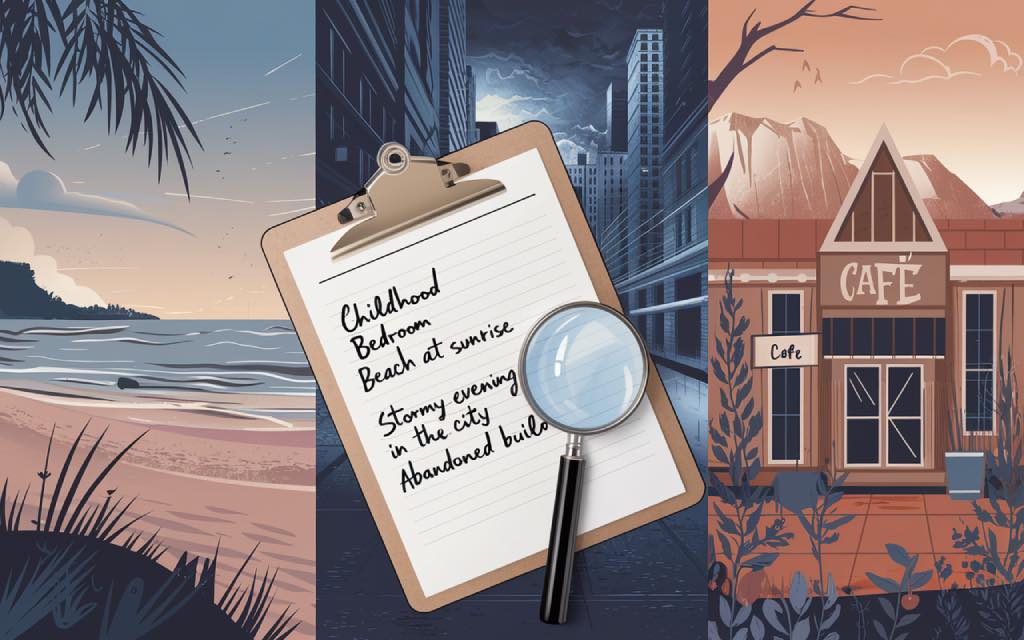

Descriptive Writing Examples

This section moves from theory to application. The following examples demonstrate the operational difference between a report of facts and the construction of a scene, between listing attributes and transmitting a sensory experience. The transformation hinges on the activation of specific sensory data and the use of definitive language.

From Report to Descriptive Scene

- Topic: An Autumn Forest

- Report: The forest was nice. Trees were everywhere, and the air smelled good.

- Descriptive Scene: The forest was a vault of gold and amber. Late afternoon sun pierced the canopy, gliding leaves that rustled with a dry, papery sound. The air carried the clean, mineral scent of damp earth and the faint, sharp perfume of decaying pine needles.

- Topic: A Busy Coffee Shop

- Report: The coffee shop was busy. People were talking, and there was a coffee smell.

- Descriptive Scene: The coffee shop hummed with low conversation, a steady undercurrent beneath the sharp hiss of the espresso machine. The air hung thick with the oily aroma of dark roast and the sweet, buttery scent of warming pastries. At the window, raindrops traced slow paths down the glass, blurring the world outside into a watercolor smear.

- Topic: A Stormy Evening

- Report: The storm was bad. It was dark and windy.

- Descriptive Scene: Anvil-shaped clouds swallowed the evening light. Wind lashed the trees, straining branches into frantic arcs. Each lightning flash froze the landscape in stark, blue-white relief, followed by a thunderclap that vibrated in the chest.

Analytical Comparison

The descriptive versions perform distinct work:

- They establish a dominant impression (“vault of gold,” “hummed,” “anvil-shaped clouds”).

- They populate that impression with precise sensory evidence (“dry, papery sound,” “oily aroma,” “vibrated in the chest”).

- They employ figurative language as a tool of precision, not ornament (the forest as a “vault,” the rain creating a “watercolor smear”).

The report states a classification (“nice,” “busy,” “bad”). The description builds an environment. The writer’s task is to select the strategic details that will trigger this vivid construction in the reader’s mind.

Further Reading

How to Write a Good Descriptive Paragraph by Richard Nordquist, ThoughtCo.

The Power of Descriptive Writing by JL Rothstein, jlrothstein.com

Excerpts of brilliant descriptive writing on writingforums.org

Description: The Good the Bad and the Just Please STOP by Kristen Lamb, authorkristenlamb.com