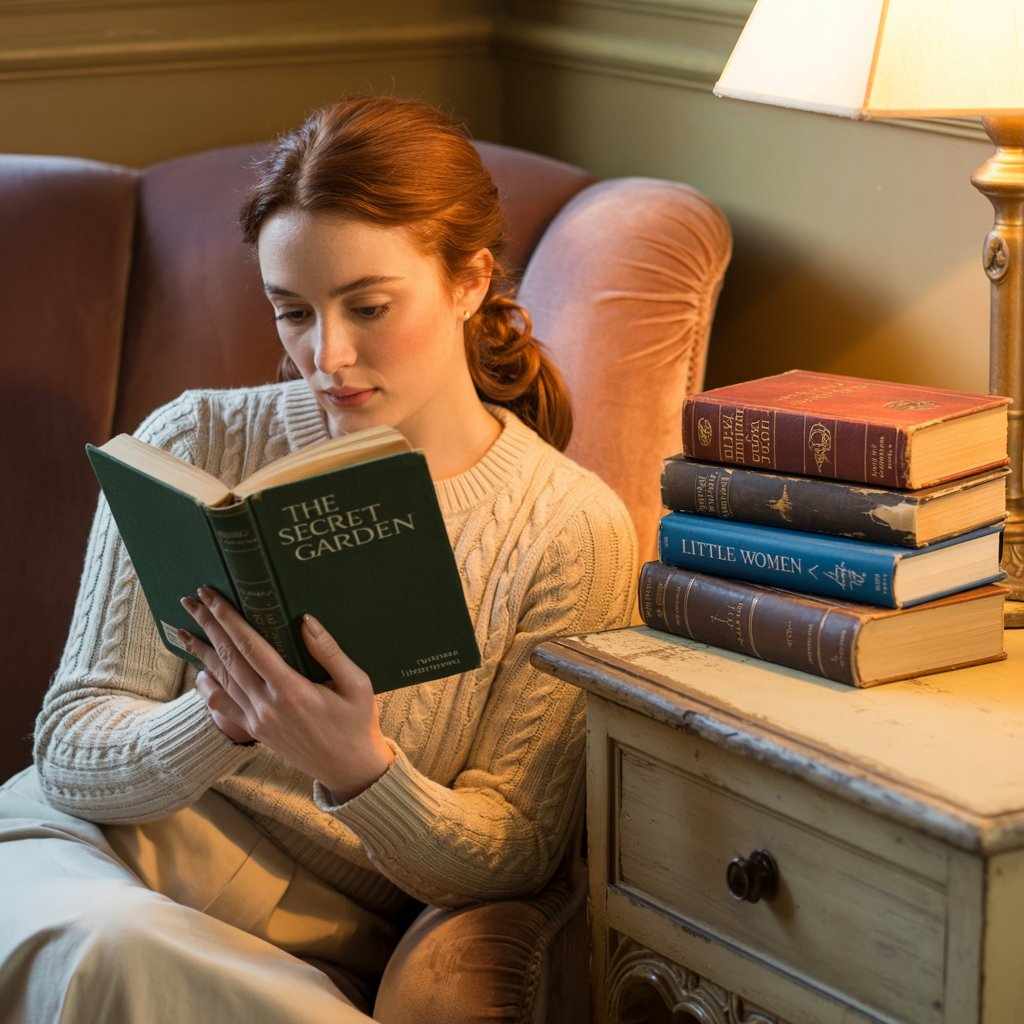

Every reader forms a reading life differently. Some prefer the sustained immersion of a single book, moving through it from first page to the last with unbroken focus. Others keep several titles in response to shifting moods, intellectual appetites, and the ebb and flow of daily life.

A novel might be left on the arm of a chair, a biography reserved for quiet evenings, and an essay collection scheduled for reading on a weekend morning. To the casual observer, such a pattern can look like distraction or lack of focus. In practice, it is often a deliberate way of moving among books with purpose and continuity.

The Appeal of Parallel Reading

Readers who keep several books in progress often speak of the calm satisfaction that comes from variety. The appeal rests not only in the range of subjects but also in the release it offers from staying within a single tone, pace, or style for too long. By shifting focus, a reader can re-engage with each book with renewed attention, carrying fresh impressions from one into the reading of another.

A Reader’s Version of Cross-Training

Much like athletes diversify their workouts to exercise different muscles, readers may seek variety in their mental engagements. A dense historical novel can be balanced by a lighthearted memoir, while a work of philosophy can be paired with contemporary poetry. Alternating between books lets readers pace themselves, giving each work its own mental space while preventing fatigue.

The contrast between styles and subjects also allows certain qualities in each book to stand out more vividly. A contemplative essay may seem sharper when read alongside a fast-moving thriller, while a lushly descriptive novel can feel even more immersive when alternated with sparse, declarative prose. The act of reading multiple books functions not only as additive but creates a more heightened awareness of each work’s character.

The Mood-Driven Library

Some readers choose what to read based on how they feel in a given moment. The same reader who enjoys an epic fantasy in the stillness of the evening might prefer an essay collection over breakfast. Keeping multiple books active creates the flexibility to match the tone, pace, and demands of the text to their energy level and mindset at any time.

This mood-aligned reading can also sustain momentum in a way that single-book reading cannot. If one text becomes emotionally heavy, the reader may turn to another that offers respite. The alternative would be to stop reading altogether until the mood changes, but by keeping several books in play, the reader ensures that there is always something fitting to return to.

Psychological Drivers

The decision to read more than one book at a time often arises from underlying cognitive tendencies and personality traits. These include the craving for novelty, the desire to manage mental effort, and the need for balance between challenge and comfort. Understanding these drivers sheds light on why this habit feels natural to some and alien to others.

Curiosity and Novelty-Seeking

Humans are wired for novelty, and books offer one of the most portable forms of newness. A fresh book represents unexplored ideas, unfamiliar voices, and untrodden paths. For readers with strong exploratory impulses, moving between books can be a purposeful act of sampling a broader intellectual range, rather than an act of abandoning the previous text.

This impulse is not inherently fickle but simply reflects a willingness to explore multiple intellectual avenues at once. Just as a researcher might consult several sources while investigating a topic, the multi-book reader constructs a reading life as a mosaic, something to draw from with each active book when trying to form a richer composite of thought.

Cognitive Rest Through Alternation

Switching between books can function as a form of cognitive rest. When a narrative becomes too emotionally charged or intellectually taxing, shifting to a different work offers a pause without disengaging from reading altogether. This mirrors how some people alternate between tasks to avoid burnout while still maintaining productivity.

Such alternation can also prevent a book from becoming stale through overexposure. If one stays too long with a single work, its style or pacing can begin to dull the senses. By stepping away and returning later, the reader can restore freshness and maintain enthusiasm for the work.

The Art of Engaging with Several Works in Tandem

Some readers treat concurrent reading as more than convenience in that it becomes a purposeful way of creating dialogue between texts. When books are chosen with these factors in mind, the experience can be intellectually rich, producing connections that deepen the appreciation of each book.

Complementary Texts in Parallel Reading

Pairing books that address similar themes or historical contexts can create a layered reading experience. For instance, a reader might approach a historical novel set in early 20th-century Japan alongside a memoir written by someone who lived through that period. The fiction provides interior texture, while the nonfiction offers direct historical grounding, each enhancing the other.

This interplay between fact and fiction, or between contrasting styles, can deepen the reader’s grasp of the subject or theme. Seeing how two different works address the same subject can bring differences in style, focus, and perspective into clearer view, leading to a fuller grasp of the topic than either would offer alone.

Serendipitous Connections Across Genres

Unplanned crossovers happen when reading several books concurrently. A symbol in a modernist short story might unexpectedly echo an image from a contemporary political biography, creating thematic linkages that a single-book focus might never reveal. These coincidences can be intellectually rewarding, making multi-book reading a kind of private literary conversation.

Such connections are often fleeting and would go unnoticed without the simultaneity of the reading. They can give the impression that the books are in silent conversation with one another, and for some readers, this sense of hidden coherence is one of the great pleasures of starting multiple books within the same span of time.

Situational and Practical Factors

While psychological tendencies explain much of the habit, practical considerations also play a role. Where, when, and how one reads can naturally lead to having several books in progress.

Accessibility and Context

In practical terms, people often keep different books in different places: one by the bed, one in a bag for commuting, and one at a work desk. The format can also dictate the choice of what to read: an audiobook for travel, an ebook for convenience, and a printed volume for long reading sessions.

This distribution of reading formats makes it easy to pick up whatever is at hand, which in turn encourages concurrent reading. Over time, these parallel reading tracks can feel as familiar as sustaining several conversations at once.

Interruptions and Life’s Pace

Life’s unpredictability can also interrupt immersion even in a highly engrossing book. Work demands, personal obligations, or emotional events may stall one reading project, leading a reader to start another that better suits their current circumstances. This shift isn’t always a conscious decision but often serve as a form of adaptation.

Furthermore, life’s interruptions can pull a reader away from a book for reasons that have nothing to do with its quality. Sometimes, the pause is brief; at other times, it stretches into weeks or months. In both cases, having other books underway ensures that reading continues even when one title is temporarily set aside.

The Risk of Abandonment

Reading several books in the same period carries the inherent risk of leaving some unfinished. Although this does not always present a problem, it does raise questions about how readers balance the breadth of their interests with the commitment required to see each book through to the end.

When Parallel Reading Leads to Neglect

Reading several books concurrently can sometimes cause one or more to be sidelined indefinitely. This may happen when a new book’s pull is stronger, when the earlier work’s pace falters, or when its subject no longer aligns with the reader’s mood. For some, this is a benign outcome; a book unfinished is simply one not suited to the current moment.

However, the temptation of a new book can overshadow the appeal of one already in progress, especially if the earlier work is demanding or slower-paced. When interest wanes, a book may drift out of the active rotation, its bookmark becoming a subtle marker of abandonment. For some readers, this carries no consequence; for others, the sight of unfinished books can create unease, as if each represents an unfulfilled commitment.

Strategies to Maintain Balance

Some readers set informal rules to avoid neglecting books:

- Rotating between books on a schedule

- Assigning certain times of day for specific titles

- Using bookmarks with notes to quickly reorient when returning after a long break

Readers who want to avoid neglect often adopt informal systems. These habits can help maintain continuity across multiple reading threads. They make it easier to sustain parallel reading without allowing any one book to vanish entirely from focus.

Literary Examples of Multi-Book Reading

Writers have long been aware of the fragmented, overlapping nature of reading, and some have woven it into their work. Each work cited in the following sections employs an unconventional structure that turns the experience of concurrent reading into part of the artistry. What could appear to be a piecemeal method becomes an intentional design that demonstrates how attention divided across multiple threads can enhance engagement with each.

Fiction Reflecting the Habit

The phenomenon itself occasionally appears in literature in ways that foreground the act of keeping several threads active at once. In If on a winter’s night a traveler (1979), Italo Calvino builds an entire novel around a reader who is repeatedly drawn into new books before finishing the ones already begun. The protagonist moves from one narrative opening to another, each time interrupted just as the story gains momentum. This cycle mirrors the restless curiosity of readers who juggle multiple works, always chasing the promise of the next page in a different book.

Calvino uses this discontinuous structure not as a gimmick but as an exploration of the reading process. Each new fragment comes from a different imagined book, shifting in style, tone, and subject, so that the act of moving between them becomes part of the narrative’s texture. The unfinished nature of every embedded story creates an ongoing tension between satisfaction and deferral, reflecting both the frustration and exhilaration that can accompany a multi-book reading habit.

Characters as Omnivorous Readers

In The Golden Notebook (1962), Doris Lessing presents its central character, Anna Wulf, a writer who maintains several notebooks, each dedicated to a specific aspect of her life. While these are notebooks rather than books, the effect is similar to concurrent reading: multiple strands running in parallel, simultaneous engagement that mirrors multi-book consumption.

This parallel structure positions the reader to experience Anna’s inner and outer worlds in alternating sequences, each colored by the context of the others. The thematic overlap between notebooks produces recurring motifs and contrasts, just as reading several unrelated books can produce unexpected connections.

Layered Narratives and Multi-Threaded Footnotes

Beyond Calvino and Lessing, other authors have crafted works that incorporate multiple texts or storylines running in parallel. In Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves (2000), the novel itself is a multi-layered puzzle: it focuses on a fictional documentary film (“The Navidson Record”) presented as a story-within-a-story, in the form of a manuscript discovered by the narrator.

The novel’s narrative is polyphonic—Johnny Truant, the narrator, inserts extensive footnotes about his own life even as he edits the manuscript, which forces the reader to juggle the eerie house story and Truant’s unraveling psyche at the same time. This ergodic structure (complete with footnotes, appendices, and even pages that must be rotated to be read) effectively makes the reader engage with multiple intertwined narratives concurrently, simulating the experience of reading two books at once within a single volume.

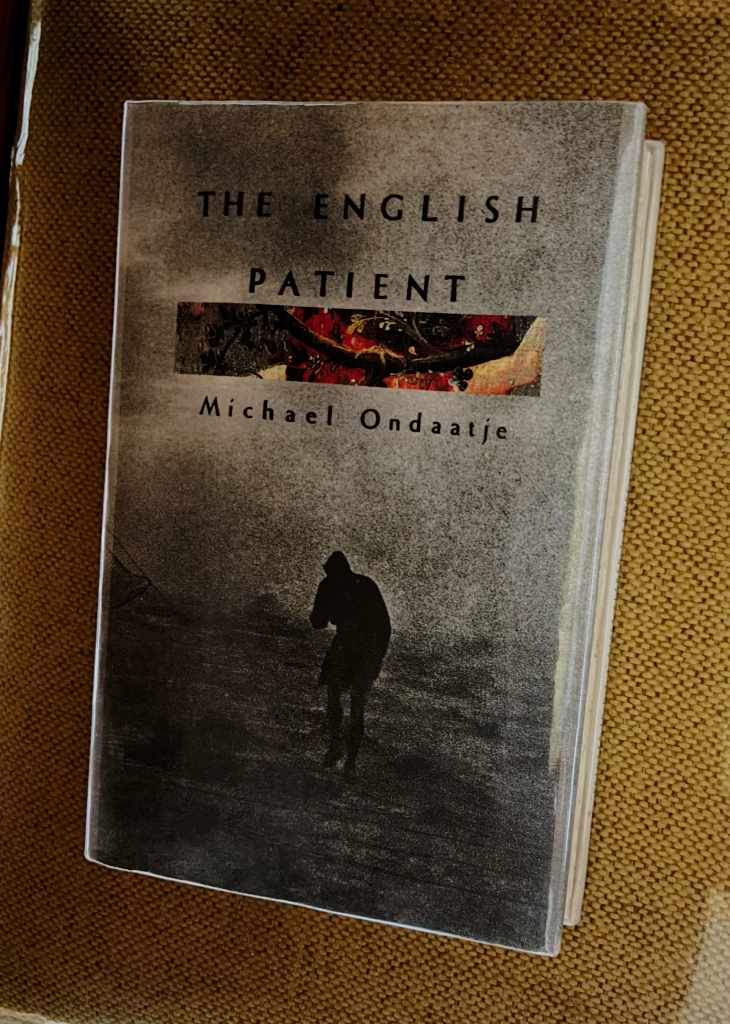

Dual Texts and Interwoven Commentary

Another inventive example is Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire (1962), which presents a 999-line narrative poem by a fictional author, John Shade, along with an obsessive commentary by an equally fictional editor, Charles Kinbote. The poem and the commentary together form a dual narrative: as Kinbote annotates the poem, he increasingly tells his own story in the footnotes.

Critics note that Pale Fire can be read in a single continuous thread or by moving between the poem and the commentary. In practice, readers often find themselves flipping back and forth between Shade’s poem and Kinbote’s elaborate notes, essentially reading two interlocked texts in parallel. This split form highlights the concurrent engagement with two different but connected strands of content, much like reading two books side by side and discovering how one illuminates the other.

Nested Storylines and Temporal Shifts

Likewise, David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas (2004) offers a modern take on concurrent narratives through its nested “Russian-doll” story structure. The novel is composed of six distinct stories set in different times and genres, arranged such that each story is interrupted by the next, only to be completed in the latter half of the book. For example, a character in one tale reads the letters or diary that comprise the previous tale, linking the stories as texts within each other.

Each narrative in the book is framed within the next and linked by an element embedded in the text, whether it be a cited document, a collection of letters, or a novel that exists inside the world of the succeeding story. As a result, the reader must hold multiple storylines in mind, recalling the half-read tale that was paused while moving through another. Mitchell concludes the tales in reverse order, so the reader finally returns to each earlier story with fresh perspective from the others.

The intricate format of Cloud Atlas essentially requires a form of parallel processing, as the reading experience demands the continuous interweaving of six interrelated narratives—a literary echo of keeping multiple books open and progressing in each simultaneously.

Further Reading

The Benefits of Reading Two Books at Once by Laura Dave, Time

If You Want to Read More, Read Multiple Books at the Same Time by Dr Nuur Hassan, Medium

Parallel Reading and Tips for Reading More Books by Avil Beckford, The Invisible Mentor