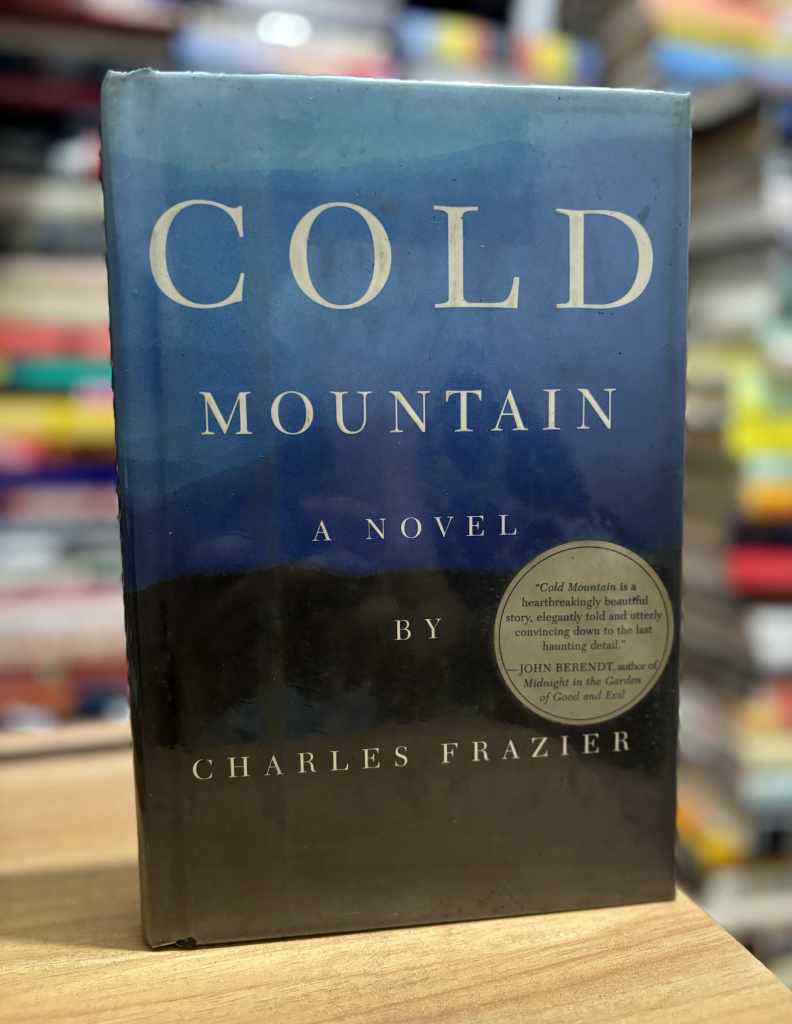

The publication of Charles Frazier’s Cold Mountain (1997) significantly expanded the possibilities of the historical novel, achieving a reputation for its powerful synthesis of epic narrative sweep, finely etched character studies, and an unyielding commitment to atmospheric authenticity. Its reputation is sustained by the meticulous research woven into the narrative and the distinctive precision of its prose, thus earning recognition across scholarly commentary and the wider literary community as an exemplary fusion of historical rigor and literary excellence.

Historical and Geographic Anchors

Set within the Appalachian highlands, Cold Mountain derives significant narrative power from the rugged terrain, a presence that stands as prominently as plot or character development. The mountain acts as both a physical landmark and a symbolic presence, its slopes and valleys formed through natural pressures and historical upheaval. The region carries its distinct contours along with the lasting marks of human activity and conflict.

Frazier renders the environment with careful attention to local rhythms and speech by capturing the textures of Appalachian life without reducing it to a backdrop. The text foregrounds the living details of flora—white pines, rhododendrons, medicinal herbs—alongside the seasonal labor and cultural practices that structure daily life. Rural spaces emerge as domains built from accumulated and practical knowledge. Farming rituals, song cycles, and oral traditions combine to form a coherent and self-sustaining world.

Figures such as Swimmer—anchored in ancestral memory by his Cherokee heritage—illustrate the continuity of the past within present struggles. Through the interaction of landscape, ritual, and language, Frazier conjures an Appalachian South that is both intricate and immediate—a region where enduring traditions coexist with the forces of historical change, and where environment and culture continually define one another.

Character Journeys: Inman and Ada Monroe

The book’s structure is defined by the dual, parallel journeys of Inman, the wounded Confederate deserter, and Ada Monroe, the orphaned preacher’s daughter striving to survive alone after her father’s death. The intertwined paths of Inman and Ada evolve through alternating chapters, each steeped in its distinct atmosphere. Their separation (and eventual reunion) remains at the heart of their story, made tangible by the yearning and uncertainty that accompanies each stretch of distance and every passing season.

Inman’s journey, modeled on the trials found in Homer’s Odyssey, begins with his departure from a war hospital. His subsequent encounters—a grieving widow, a preacher lacking moral clarity, men who exercise authority through violence—serve not simply as barriers, but as indicators of the shifting realities within his path. Each meeting triggers a reassessment of beliefs and intentions, which show how conflict defines both personal history and future choices.

Ada’s transformation, by contrast, is not marked by dramatic events. She leaves behind the refined gentility of Charleston for the demanding life of working the land, guided by Ruby, a local woman whose deep, practical knowledge was rooted in rural Appalachia. Together, they build a life around the rhythm of daily tasks—milking, mending, and preparing for the turn of each season. Their partnership, a fusion of Ada’s intellect and Ruby’s practical skills, becomes a dynamic exchange where both must learn and adapt.

Themes and Literary Significance

The novel’s preoccupations stretch well beyond the devastations of war or the longed-for reunion that seems to propel its surface narrative. Beneath the movement of plot lies a meditation on the meaning of home—a place at once geographical, emotional, and metaphysical.

Through Inman’s journey, Frazier reanimates the ancient patterns of a homecoming found in Homer, yet he situates it within the distinctly troubled terrain of nineteenth-century America, where memory becomes the contested ground. The wounds of battle avoid closure, with peace appearing less as a conclusion than a fragile interlude. These subtle observations accumulate, proposing that true revelation dwells in the discipline of attention over grand finality.

While war imparts the novel its temporal urgency, its emotional architecture depends on the gradual recalibration of those who survive it. The text’s ethical inquiry lies in the negotiations its characters undertake: how to act when every rule of faith, propriety, or affection has been stripped of certainty. Their gestures toward beliefs shift constantly, never achieving permanence. In this fluidity, the novel locates its moral depth by showing conviction as a pattern of decisions continually tested by necessity.

Nature and Spirituality

Frazier’s depiction of the Appalachian terrain transcends the function of a setting; the environment operates as an active impetus with its own capacity to inflict harm, provide care, or demand humility from those occupying it. Ritual and revelation are woven into daily work, all governed by the land’s unyielding terms. The local flora and fauna, as well as omnipresent climatic forces, serve as agents of transformation. Inman, for example, draws continuously on weather signs, plant lore, and the old ways, demonstrating a reliance on knowledge systems that predate both the war and his journey.

Gender and Trauma

A discerning aspect of the narrative lies in its examination of gender roles and the enduring effects of trauma. Contemporary scholarship observes how the novel marks psychological and physical hardship through the experiences expected of men and women: Inman’s pursuit of fortitude reflects the ideal of gentle perseverance, whereas Ada’s solitary struggle foregrounds a form of resilience that blends emotional fortitude with newfound practical competence.

Ruby’s role complicates these polarities; her agency is neither merely reactive nor in imitation of existing archetypes. Instead, she asserts herself through collective engagement and pragmatic support, contributing a model of partnership grounded in reciprocal effort rather than traditional hierarchies.

Community, Isolation, and Reconciliation

The dissolution of familiar bonds driven by the upheavals of war and economic devastation forces a reconfiguration of social relations. Ada and Ruby’s working relationship stands as a testament to the alliances formed from necessity. The novel further attends to the shifting boundaries of community through encounters with those cast aside: itinerants, the uprooted, and survivors navigating the margins. These episodes underscore the fragility of trust and the necessity of improvising connection in the face of danger. Solitude, in this context, is both a source of exposure and an occasion for self-scrutiny, holding the potential for renewed purpose or for more profound uncertainty.

Literary Structure and Technique

A major structural feature of the novel lies in its dual protagonists: W. P. Inman on his odyssey through war-torn terrain, and Ada Monroe, the minister’s daughter trying to hold together a farm near Cold Mountain after relocation from Charleston. These alternating viewpoints contribute to the narrative breadth and depth: the outward journey of Inman set against the home front challenges for Ada.

The prose style relies on an admixture of archaic phrases, dialect-inflected dialogue, and precise sensory details. Meticulous imageries of rain-soaked fields, the feel of rough homespun, or the toll of distant gunfire ground the reader in texture as much as plot. Dialogue operates as the prime engine of character revelation; elliptical exchanges with tacit understandings convey what gesture and action cannot. The novel’s careful orchestration of irony, foreshadowing, and episodic structure honors the form of oral storytelling, linking its characters to broader literary ancestry.

Symbolism and Allusions

Symbols in Cold Mountain cluster in motifs of travel, stasis, and cyclical change. The mountain itself, referenced repeatedly, marks both geographic destiny and spiritual calling. The allusions—most notably to The Odyssey, but also to American folk legend and Native tradition—function as channels for thematic exploration rather than mere homage. The reconstruction of the farm, the journey through wild terrain, and the moments of reunion are freighted with significance that reaches beyond narrative necessity.

Intertextual Connections

Frazier’s book claims kinship with other works in the historical fiction canon. Connections to William Styron’s The Confessions of Nat Turner (1967), Barbara Kingsolver’s Prodigal Summer (2000), and David Guterson’s Snow Falling on Cedars (1994) emerge through shared investment in setting, style, and moral complexity. Each of these titles, while unique, marshals historical circumstance for the purpose of philosophical inquiry, contributing to the broad matrix in which Cold Mountain is situated.

Reception and Critical Legacy

Upon publication, Cold Mountain achieved both commercial success and scholarly acclaim, receiving the National Book Award for fiction. Critics cited the book’s refusal to romanticize war, its granular portrayal of hardship, and its historical fidelity as major advances for the historical novel form. Recent scholarship revisits Frazier’s activism in resituating the Appalachian world within national consciousness, invoking regional pride through literary means.

Ongoing work by literary scholars situates Cold Mountain as part of a tradition that examines identity, migration, violence, and reconciliation. Studies emphasize its contribution to debates over trauma, ecological knowledge, and shifting gender roles in American fiction. The novel is still generating discussion around motifs of exile, forms of hope, and the boundaries between narrative and history.

Interviews with the author highlight his commitment to research, oral histories, and the preservation of endangered dialects and customs. For readers seeking Civil War fiction with intellectual rigor and poetic energy, Cold Mountain remains a vital recommendation—it does not stand simply as a generic genre piece but as a distinctive literary achievement that blends personal and historical vision.

Cinematic Adaptation

Anthony Minghella’s 2003 film adaptation translates Frazier’s novel into a cinematic language that is both faithful to its source and distinctly its own artistic achievement. The film condenses the novel’s sprawling, episodic narrative by sharpening its focus on the central love story and through visual and aural techniques for externalizing the novel’s internal, atmospheric preoccupations. Minghella’s directorial vision captures the epic scale of Inman’s odyssey and the intimate confines of Ada’s struggle, with the camera acting as a meticulous observer of both human emotion and nature’s details.

Where the novel luxuriates in the interiority of its characters’ thoughts, the film masterfully translates psychological intricacy into image and gesture. Jude Law’s portrayal of Inman communicates a profound world-weariness through gestures and gaze, while Nicole Kidman’s Ada embodies a transformation from ornamental delicacy to resilient capacity. The film’s most significant narrative breakthrough—the elevation of Ruby’s role, played with earthy wit by Renée Zellweger—proves to be an interpretive masterstroke. It crystallizes the novel’s thematic concern with pragmatic female alliances, making the partnership between Ada and Ruby a dynamic, central pillar of the story.

Cinematographer John Seale paints the landscape as a character of equal importance: the fog-laden valleys, the brutal beauty of the seasons, and the haunting stillness of deserted farms are not mere backdrops but active agents controlling the narrative. The film’s soundscape, from the stark serenity of snowfall to the sudden brutality of wartime violence, works in concert with the visuals to create a sensory experience of a world both majestic and unforgiving.

While making necessary concessions to the commercial demands of Hollywood, particularly in streamlining the novel’s more ambiguous ending, Minghella’s adaptation succeeds in preserving the core of Frazier’s work: a meditation on the erosions and tenacities of the human spirit, set against a land that witnesses both. It stands not as a replacement for the novel, but as a resonant and complementary artistic vision.

For a closer look at how Charles Frazier’s language crafts narrative, see our discussion of poetic narrative style in “Poetic Prose in Fiction: How Arundhati Roy and Charles Frazier Compose Story Through Language.”

Selected Passage with Analysis

Without pausing even for salutation Inman said, Who put out your pair of eyes?

Pages 5-6, Cold Mountain by Charles Frazier

The blind man had a friendly smile on his face and he said, Nobody. I never had any.

—Why did you never have any? Inman said.

—Just happened that way.

—Well, Inmad said. You’re mighty calm. Especially for a man that most would say has taken the little end of the horn all his life.

The blind man said, It might have been worse had I ever been given a glimpse of the world and then lost it.

—Maybe, Inman said. Though what would you pay right now to have your eyeballs back for ten minutes? Plenty, I bet.

The man studied on the question. He worked his tongue around the corner of his mouth. He said, I’d not give an Indian-head cent. I fear it might turn me hateful.

—It’s done it to me, Inman said. There’s plenty I wish I’d never seen.

—That’s not the way I meant it. You said ten minutes. It’s having a thing and the loss I’m talking about.

This passage presents a layered meditation on perception, loss, and moral perspective. Inman’s direct question about the blind man’s eyes establishes the novel’s unflinching attention to human vulnerability. The blind man’s calm response challenges conventional assumptions about suffering, with Frazier using this encounter to highlight the relativity of misfortune, a recurrent theme throughout the novel where characters’ endurance often depends on how they interpret their circumstances.

The dialogue also probes the ethical and emotional consequences of experience. Inman imagines the value of temporary sight, while the blind man refuses any compensation, recognizing that knowledge of the world — and potential loss — can cultivate bitterness. This exchange reflects broader tensions in the novel: exposure to human cruelty, war, and hardship influences perception and longing, inducing both insight and regret.

Structurally, the episode exemplifies the novel’s episodic, encounter-driven design. Each meeting offers reflection on resilience and moral reckoning. Here, vision becomes both literal and figurative, examining how perception, experience, and interpretation define ethical life, a motif that permeates Inman’s journey and Frazier’s depiction of the Appalachian South.

Further Reading

Cold Mountain by Charles Frazier, John Mullan of The Guardian

Week three: Charles Frazier on writing Cold Mountain, The Guardian

Life after ‘Cold Mountain’ by John Marshall, seattlepi.com

Thoughts on Cold Mountain on Reddit