My Reading Note

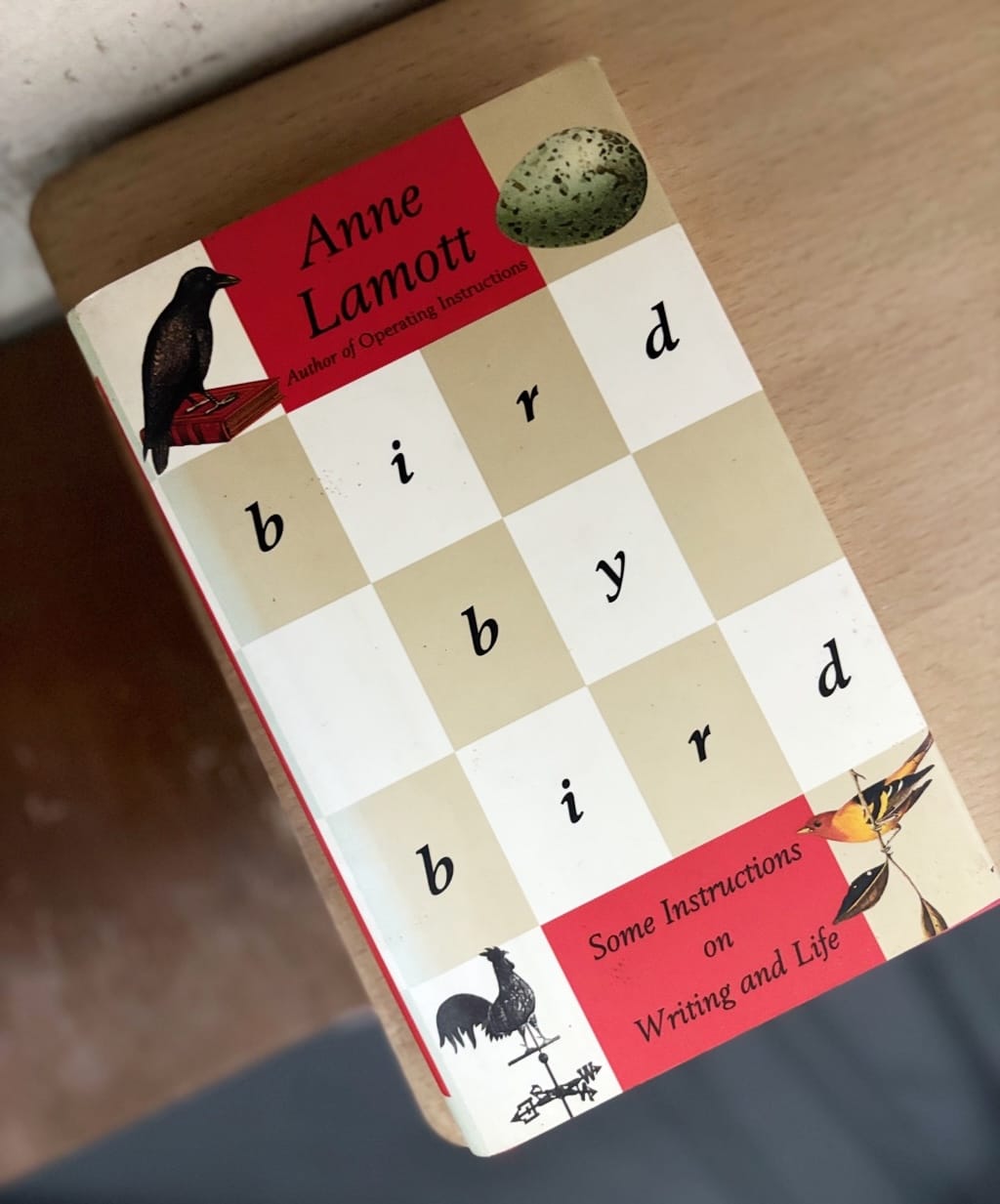

I first read Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird during a period of intense writer’s block, and it has remained on my desk ever since as a permission slip: it kind of serves as my license to write haphazardly on the first draft, to let my thoughts flow freely.

While often received as a compassionate manual for overcoming creative doubt, Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life (1994) is actually a structured, pragmatic philosophy for managing the psychology of creation, a system for the writing process that advocates for incremental progress, radical self-acceptance, and a commitment to emotional honesty.

This article examines Bird by Bird as “The Lamottian Framework”: a coherent, three-part model of applied pragmatism designed to defeat creative stasis by systematically decoupling action from judgment. This framework hinges on a principle that philosophy of art should address problems arising for creative practitioners and offer solutions that promote intensive reflections on the practice. Lamott’s book is an embodiment of this principle, translating abstract anxieties into an actionable set of protocols.

This book serves as my philosophical reset button, a reminder that the primary barrier to writing the first draft is often epistemological—the mistaken belief that one must know the whole before beginning any part.

The Architecture of a Practical Philosophy

Lamott’s contribution lies in her translation of abstract challenges into tangible, character-driven metaphors. The titular “bird by bird” advice transcends a simple tip for productivity; it formulates a worldview that recasts overwhelming projects as a series of conceivable, non-threatening actions. This reframing of the concept establishes the necessary condition for her most famous edict: the necessity of the “shitty first draft.”

This concept functions as a cognitive tool engineered for a specific task. By sanctioning imperfection from the outset, Lamott seeks to disarm the internal critic and the perfectionist—personifications she constructs as persistent antagonists within the writer’s psyche, moving beyond their simple classification as obstacles. This act of personification grants the writer a critical distance by creating a space to engage with these anxieties, to recognize their predictable arguments, and to elect a stance not governed by them.

I often consider Lamott’s inner critic alongside Virginia Woolf’s “angel in the house.” Both are internalized figures of constraint—one enforcing patriarchal decorum, the other enforcing an impossible standard of polished genius. Silencing them is not a one-time act but a daily practice of refusal.

Deconstructing the Lamottian Framework

Lamott’s philosophy can be formalized into a tripartite model, each component addressing a specific failure mode of the aspiring writer.

- The Protocol of Imperfect Genesis (The “Shitty First Draft”): This is the cornerstone of the framework. Lamott’s famous injunction to write shitty first drafts is more than permission to write poorly; it is a strategic redefinition of the draft’s purpose. This protocol intentionally severs the creative act from the critical act by recognizing that simultaneously writing and critiquing induces paralysis. The goal is to create without evaluating, a process of creation with protected cognitive space for exploration.

- The Principle of Incremental Action (“Bird by Bird” and the “One-Inch Picture Frame”): This principle attacks the problem of overwhelming scope. Faced with a monumental task, the writer is instructed to reduce their focus to a “short assignment” or what fits in a “one-inch picture frame.” This is a cognitive management technique that bypasses the prefrontal cortex’s panic at large projects by forcing attention onto a single, manageable component. Progress accrues through the accumulation of completed micro-tasks, a metric that displaces the daunting benchmark of the finished whole.

- The Ethic of Vulnerable Truth-Telling: Lamott argues that “good writing is about telling the truth.” This moves the writer’s focus from external validation (“Is this good?”) to internal fidelity (“Is this true?”). By framing the writer’s obligation as one of emotional honesty (“writing straight into the emotional center of things”), she provides a moral and motivational compass that exists independent of market forces or perceived talent. The reward shifts from external validation to the integrity found within the act of faithful self-expression.

The genius of shitty first drafts is their strategic realignment of the draft’s purpose. It’s not a failed version of a final product; it’s the essential, chaotic raw material from which a final product is excavated. This distinction separates the act of creation from that of critique at the physiological level.

I’ve always read Lamott’s “truth” not as factual accuracy, but as phenomenological honesty. It’s the difference between describing a childhood kitchen with generic details and capturing the specific, greasy feel of a particular light switch that always gave a slight shock. The latter contains a truth that technique alone cannot fabricate.

Writing as an Act of Truth-Telling

Beyond process, Lamott elevates writing to a moral and exploratory imperative. The goal shifts from producing something “good” to uncovering something “true.” She argues that the writer’s obligation is to “risk placing real emotion at the center of your work” and to “write straight into the emotional center of things.” This focus on vulnerability transforms writing from a display of skill into an instrument of self-discovery. The page becomes a mirror compelled to reveal the writer’s unadmitted fears, casting aside wished-for portrayals.

In my opinion, however, the Lamottian Framework is exceptionally effective for initiating creative work and managing the anxiety of beginnings, but it provides less guidance for the sustained, structural revision required in the intermediate and final stages of a complex project.

This journey necessitates a specific observational discipline. Lamott advocates for a heightened attention to the particulars of daily life—the textures, dialogues, and fleeting moments that most overlook. This practice grounds the writer in reality by providing the authentic details that prevent writing from becoming abstract or sentimental. Honesty in observation becomes the foundation for honesty in expression.

The more I think about it, Lamott’s call for detailed observation is the practical sibling to her metaphysical call for truth. You cannot write toward the emotional center of things if you are not first anchored in the physical and social world. The universal she describes is always accessed through the granular.

Synthesis, Scope, and the Modern Inventio

The Lamottian Framework can be productively synthesized with the classical rhetorical concept of inventio (invention), the stage concerned with discovering arguments and material. Lamott effectively reinvents inventio for the modern, psychologically burdened writer. Where classical rhetoric treated invention as a systematic search, Lamott recasts it as a psychological operation: her protocols are designed to access material that fear and perfectionism have locked away. The shitty first draft is, in essence, a tool for inventio that prioritizes volume and vulnerability over judgment, ensuring the raw matter of the work makes it to the page.

Contrasts, Limitations, and Corrective Views

The framework’s limitations become clear through contrast. Its primary mode is defensive, aimed at disarming internal critics (the “voices of anxiety, judgment, doom, guilt”). It is less equipped for the proactive, architectural work of mid-process revision, where one must analyze narrative structure, thematic coherence, and logical argument. A writer proficient in Lamott’s methods may produce abundant raw material yet lack the analytical tools required to assemble a rigorous, cohesive whole.

This is why the final third of many writing projects feels like a different sport. Lamott gets you onto the field and playing freely, but winning the game often requires a different, more analytical coach—a John McPhee or a Peter Elbow—who can teach you to rearchitect what you’ve joyously built.

A significant corrective critique has also emerged regarding the framework’s foundational terminology. Some writers and teachers argue that labeling early work “shitty” is a form of preemptive self-loathing that can be damaging, especially for new writers. They contend that terms like “first draft,” “down draft,” or “exploratory draft” maintain the necessary freedom from perfectionism without the derogatory frame. This critique holds that the spirit of Lamott’s advice (to begin without judgment) is undermined by language that inherently judges the work as worthless. This presents a valid challenge: does the shock value of shittiness liberate, or does it inadvertently reinforce the very culture of disparagement it seeks to overthrow?

I understand this critique intellectually, yet I confess the term’s harshness was what originally gave me permission. It enacted a verbal shrug so profound it broke my paralysis. For me, “be kind to your first draft” would not have worked; I needed “who cares if it’s terrible?” to bypass my ingrained academic fastidiousness. The utility of the provocation may depend entirely on the writer’s pre-existing neuroses.

Captain Ahab’s Story of Revenge with “The Great White Whale”

The Analysis: Look at Melville’s digressions on cetology. From a conventional craft perspective, they appear as tangentials that interrupt the plot’s momentum. Through Lamott’s framework, they become the essential, imperfect process of a writer thinking on the page, following his curiosity “bird by bird” to build a world vast enough to contain his theme.

Reading Recommendation: To extend this conversation, pick up John McPhee’s Draft No. 4: On the Writing Process (2017). Where Lamott provides the emotional and philosophical groundwork for beginning, McPhee offers a master class in the structural mechanics of revision. Reading them together covers the full spectrum: the courage to make the initial mess and the meticulous craft needed to build from it.

To see Lamott’s principles in action, I recommend a direct engagement with her work alongside a complementary text.

Selected Passage with Analysis

If something inside you is real, we will probably find it interesting, and it will probably be universal. So you must risk placing real emotion at the center of your work. Write straight into the emotional center of things. Write toward vulnerability. Don’t worry about appearing sentimental. Worry about being unavailable; worry about being absent or fraudulent. Risk being unliked. Tell the truth as you understand it. If you’re a writer, you have a moral obligation to do this. And it is a revolutionary act—truth is always subversive.

Page 226, Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott

Lamott defines the source of consequential writing: the embrace of real emotion and vulnerability. She locates authenticity in a writer’s willingness to place true feeling at the center of the work, a practice that establishes a deeper resonance with an audience. Her directive to "write straight into the emotional center of things" champions raw expression over a crafted, detached narrative.

The passage declares a moral imperative for the writer: a duty to tell the truth. Lamott characterizes this truth as subversive, an element that challenges conventional boundaries. This obligation merges ethics with creative methods — a commitment that risks alienating readers to achieve artistic integrity.

These principles provide a foundation for work that achieves genuine impact. A writer’s commitment to emotional honesty and subversive truth creates the potential for profound connection. The result is writing that transmutes the personal into the universal, a process that secures a durable bond between writer and reader.

Further Reading

Anne Lamott on Writing and Why Perfectionism Kills Creativity by Maria Popova, The Marginalian

While There Are Still Writers: Reading Anne Lamott’s Bird By Bird by Tristan Foster, Medium

1994 Anne Lamott “Bird by Bird” at the San Francisco Public Library by San Francisco Public Library, YouTube

Am I the only person who doesn’t like Bird by Bird? on Reddit