My Reading Note

I keep reading haiku and wondering how they work. How can three tiny lines hold a whole feeling? They feel simple, but I know there’s more to them. I decided to look it up and write down what I found.

The impulse to understand how a poem works draws many to the world’s most famous short form: the haiku. This guide provides a clear starting point for anyone who wants to read haiku with more insight or try writing their own. We will break down the basic rules, explore the philosophy behind the form, and offer practical steps to begin.

The Core Structure

At its most basic, a haiku is a short, unrhymed poem. The best-known guideline is its syllabic structure:

- Line 1: 5 syllables.

- Line 2: 7 syllables.

- Line 3: 5 syllables.

This 5-7-5 pattern creates a compact, three-line structure of 17 total syllables. The lines do not need to rhyme; the power comes from the rhythm and precision. A classic example by the Japanese master, Matsuo Bashō, perfectly demonstrates this form:

An old silent pond…

A frog jumps into the pond—

splash! Silence again.

This simple structure is the foundational “rule,” but it is not the whole story. For beginners, the 5-7-5 framework is an excellent, constructive tool. As you become comfortable, you may discover that many respected modern haiku writers adapt the form, sometimes using fewer syllables to capture a moment with even greater directness.

When I first tried counting syllables, it felt rigid and awkward, like a math problem. I almost gave up, but sticking with it for a few attempts was the key. It trained my ear to hear the natural rhythm of the words.

Beyond Syllables: The “Spirit” of the Haiku

Beyond the syllable count, three key principles give a haiku its unique power.

- The “kigo” (seasonal word). Traditionally, haiku use a word or image to anchor the poem in a specific season. This isn’t just description. It connects a fleeting moment to the larger, cyclical patterns of nature. Examples include frog (ƒspring), snow (winter), or cicadas (summer).

- The “kireji” (cutting word). In Japanese, a kireji is a special word that creates a pause, contrast, or sense of closure. In English, poets often use punctuation (a dash, colon, or ellipsis) to achieve a similar effect. It acts like a pivot point, breaking the poem into two distinct parts for the reader to connect. In Bashō’s “old pond,” the dash after “pond” is a classic example.

At first, I overthought the “cut.” It’s just the natural pause where the poem turns, like a breath between two thoughts.

- A single moment of insight. The true purpose of a haiku is not just to describe something, but to capture a brief, often surprising, flash of perception—a “moment of insight”. The poem presents a clear image, then juxtaposes it with another image or thought. This creates a spark of meaning that is felt more than explained.

Consider the masterful translation by Jane Hirshfield of Bashō’s most famous haiku:

In Kyoto,

hearing the cuckoo,

I long for Kyoto.

The first line sets a place. The second presents a sensory event. The third reveals the poet’s startling emotion: he longs for the ideal of Kyoto while physically present there. The poem doesn’t explain this paradox; the stark juxtaposition lets the reader feel it directly. This is the “moment of insight.”

A Practical Method for Writing Your Own

Ready to try? Follow these steps to move from idea to draft.

- Observe and brainstorm. Haiku begin with deep noticing. Go outside, or focus on an ordinary scene. Forget “poetic” language. Jot down concrete, sensory details: the crack of a branch, steam off morning coffee, a dusty sunbeam. What season is it? A single, strong image is your raw material.

- Draft with the 5-7-5 frame. Take your central image and build it into the 5-7-5 structure. Don’t aim for a complete sentence. Think of it as building two parts: the first line often establishes a setting, while the next two present an action or a shift. Use your syllables to carve the thought down to its essence. It will feel mechanical at first—that’s part of the process.

- Revise for clarity and resonance. Read your draft aloud. Does it sound natural? Have you used a “cutting” pause (a dash or line break) to create two parts? Most importantly, does it capture a moment? Remove any abstract words (sadness, beauty) and replace them with the image that caused the feeling. The goal is to show, not tell.

In my early attempts, I tried to tell a whole story. I learned that haiku works the opposite way. It’s not about the story but the “one instant” before the story, the single spark of noticing.

The Journey, Not the Destination

Haiku teaches that limitation breeds creativity. The strict 5-7-5 pattern is not a cage, but a workshop where you learn to choose each word with care. Start by honoring the traditional rules. This discipline will sharpen your eye for detail and your ear for rhythm. With practice, you may feel confident enough to adapt the form, focusing less on the strict syllable count and more on the haiku’s core mission: to freeze a single, resonant instant in time.

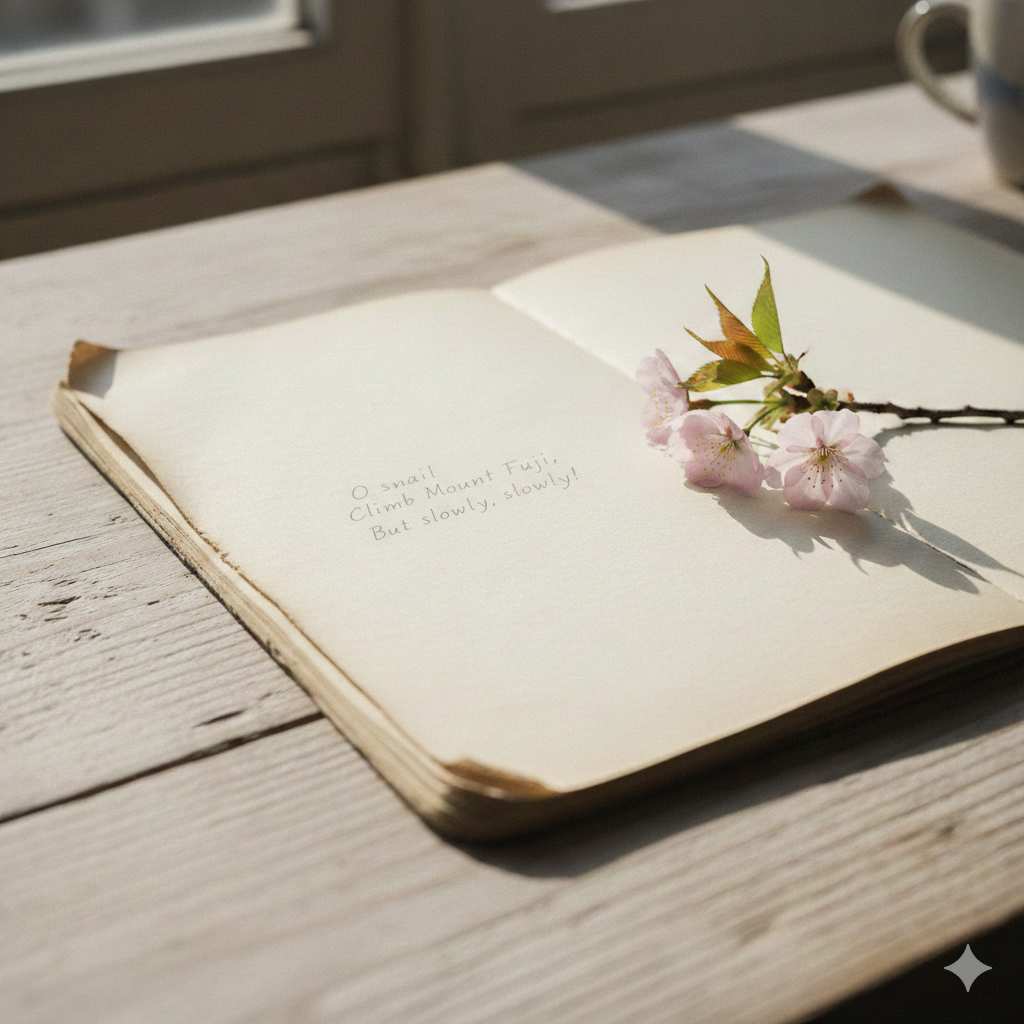

As you write, remember the words of another great haiku master, Kobayashi Issa. His advice applies to both poetry and the practice of observation it requires:

O snail

Climb Mount Fuji,

But slowly, slowly!

Further Reading

New to Haiku: How is Writing Haiku Different From Writing Prose Poetry? by Julie Bloss Kelsey, The Haiku Foundation

Punctuation in Haiku by Michael Dylan Welch, Graceguts

How to Write Haiku by Esther Spurrill-Jones, The Writing Cooperative (Medium)

[Help] How do i write a haiku? on Reddit