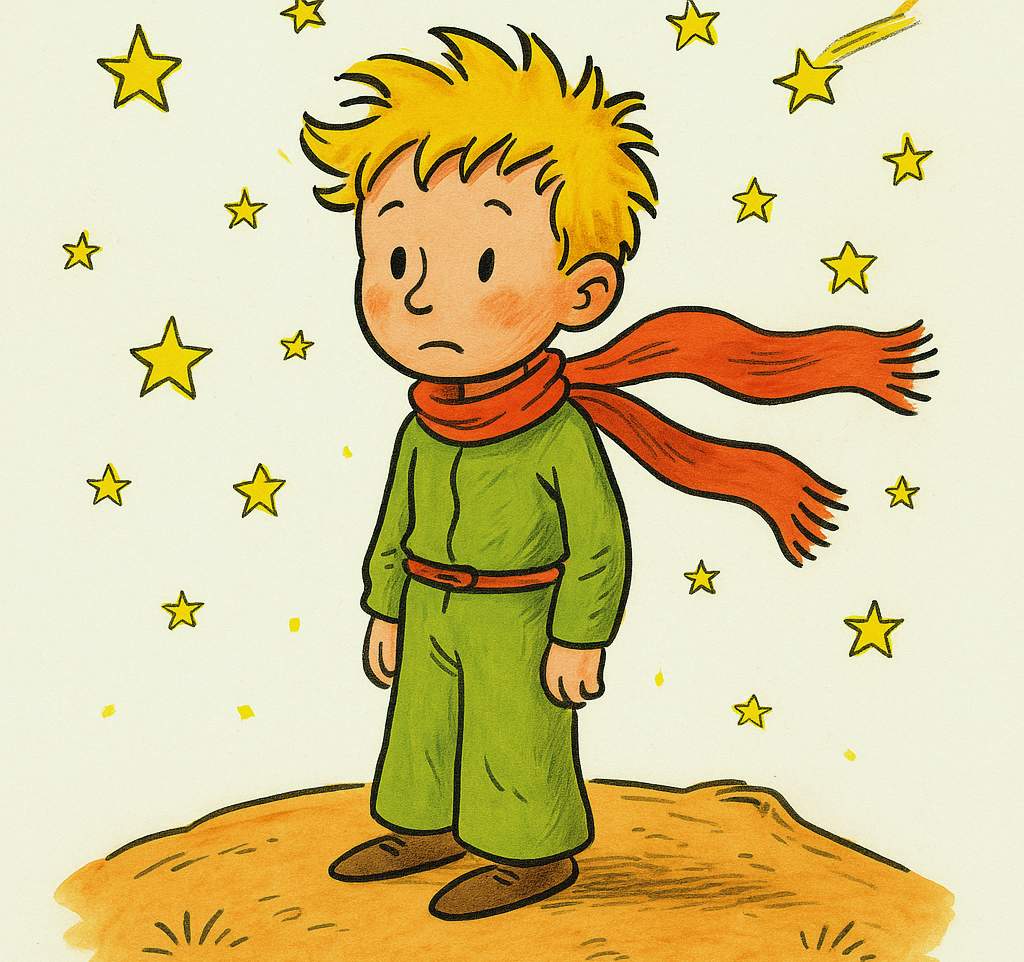

When The Little Prince (Le Petit Prince, 1943) first appeared, it was read as a children’s fable and a source of gentle comfort for adults at war. The watercolor planets, the gentle aphorisms, and the fox that spoke in riddles all suggested a modest parable of kindness and imagination. Yet beneath that lightness lies a meditation that is heavier than its form admits. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s tale conceals far deeper truths: an inquiry into how wonder erodes, how tenderness gives way to utility, and how imagination is disciplined into passive obedience.

Modern life often treats seriousness as a virtue and confuses importance with depth. It rewards speed, control, and efficiency, calling them signs of maturity. Saint-Exupéry recognized these long before they became the measure of modern success. Through the figure of the child, he reveals a world so intent on order that it no longer knows how to imagine, so consumed by doing that it no longer pauses to think. The pilot’s desert—wide and silent—mirrors the mind that has learned how to function but forgotten how to feel.

To read The Little Prince again today is not to go back to our forgotten sense of childhood wonder. Encountering it again speaks of how perception narrows with age, how certain forms of attention go unnoticed, and how small instincts for care or curiosity are gradually set aside. These changes are almost unspoken, absorbed into the pace of ordinary life. This essay begins from there, with what goes missing in plain sight, and what Saint-Exupéry’s fable still tries to make us see and feel again.

The First Loss: Utility in Place of Imagination

The book opens with a drawing: a boa constrictor digesting an elephant, mistaken by every grown-up for a hat. The narrator, a six-year-old child at the time, gives up drawing altogether after a series of adults advises him to turn his attention to more useful things. The moment is subtle but absolute, the first signal of a mind being pulled away from perception and toward compliance.

Saint-Exupéry doesn’t romanticize the child’s imagination. What he reveals is how quickly it has been corrected. The drawing is misunderstood because adults no longer expect to see anything unfamiliar, not because it is poorly rendered. What they cannot recognize, they dismiss. In this world, to imagine is to risk being misunderstood, which is also straying from sense—a risk most adults have learned to avoid.

The boa constrictor becomes more than a sketch. It marks a shift from looking closely to sorting out quickly, from seeing to deciding what something is supposed to be. The adult responds only to what fits a familiar pattern; what doesn’t appear useful is ignored. This isn’t a failure of imagination so much as a reluctance to stay with what doesn’t make immediate sense. Imagination fades slowly, diminished by what we stop noticing.

Characters the Prince Encountered in Different Planets

Before the prince arrives on Earth, he passes through six small planets, each inhabited by a single adult. These encounters form a sequence of brief but revealing portraits. The prince listens, asks questions, and moves on. What he finds in each world is a fixed mindset: a way of thinking that has hardened into routine. There is no exchange, no curiosity, no recognition that someone else has entered the room. Each adult speaks only in the terms they’ve come to believe explain everything.

These characters do not represent isolated personalities. They are types, each driven by a logic that adulthood mistakes for seriousness. Power, vanity, addiction, accumulation, routine, and abstraction: these are familiar patterns repeated until they become invisible. And through the prince’s muted bewilderment, the book draws attention to how these patterns strip away perception. What remains is a kind of competence emptied of reflection, a life structured around fixed roles rather than any real exchange with the world.

The King

The first adult the prince meets is a king who claims to rule over everything, though his planet is empty. When the prince arrives, the king immediately declares him a subject and begins to command him, but only in ways that align with what the prince is already doing. The king adjusts his orders to maintain the illusion of authority, revealing a kind of power that cannot tolerate uncertainty. Saint-Exupéry does not mock him; he simply shows how the urge to control, even when unchallenged, turns hollow. The king’s need to appear in control eventually strips away the substance of his authority.

The Vain Man

The second planet is home to a man who wants only to be admired. He hears only what flatters him and ignores anything that asks him to respond. The prince attempts conversation, but the man loops back to compliments, uninterested in anything that might shift his attention. Saint-Exupéry presents vanity as a form of emptiness: the man wants admiration without connection. The man wants to be seen, but not to be looked at too closely.

The Drunkard

On the third planet, the prince meets a man who drinks to forget that he is ashamed of drinking. When questioned, the man offers a circular answer, unable to explain his behavior but unwilling to break from it. Saint-Exupéry does not portray him as tragic, only unreachable. He no longer tries to understand his actions and instead repeats them out of habit. The drunkard becomes a figure of adult exhaustion, where the pattern continues even after its reason has faded, and the effort to examine it no longer feels worth pursuing.

The Businessman

The fourth planet is occupied by a man who counts stars and claims to own them. He does not look at them or speak of their beauty; he simply writes numbers in a ledger and locks them in a drawer. When the prince asks what purpose this serves, the man replies that he is managing them. Saint-Exupéry presents a mindset in which the act of counting becomes an end in itself. The businessman sees worth only in what can be claimed and recorded. His attention is fixed but disengaged. Nothing is offered; nothing is known. The task replaces the thing being measured.

The Lamplighter

The fifth planet is home to a man who lights and extinguishes a lamp every minute, following an old instruction that no longer fits the planet’s rhythm. He follows the rule without question, saying only that he is too busy to rest. Saint-Exupéry gives this figure more dignity than the others: the lamplighter is not vain or proud; he is simply trapped in a system that demands obedience. His labor is honest but mechanical; what began as meaningful work has hardened into rote. The prince admires his devotion but leaves him behind all the same.

The Geographer

On the sixth planet, the prince meets a geographer who records the locations of mountains, rivers, and deserts but never leaves his desk. He relies entirely on others to describe the world, asking only whether their accounts are reliable. When the prince mentions a rose he deeply cares about—a flower he has watered, protected, and grown attached to—the geographer dismisses it. Anything short-lived, he says, is not worth recording. Saint-Exupéry presents the geographer as someone who gathers facts, but nothing he collects is allowed to matter.

Characters the Prince Encountered on Earth

By the time the prince arrives on Earth, he has already seen the adult mind in six of its fixed structures. But Earth is different: here, the prince still encounters the same habits (control, distraction, iteration), but they no longer stand on their own. The figures he meets here are more varied, and not all of them speak in the same closed patterns. Some repeat what he already recognizes, while others break from it.

Still, the underlying tension remains. Each figure, whether person, creature, or image, reflects adulthood from a distance. Some reveal what has been worn down over time; others suggest that attention, once lost, might still be restored. In each case, Saint-Exupéry circles back to the same unassuming question: what happens when maturity narrows the field of vision?

The Snake

The first creature the prince meets on Earth is a snake. Its words are sparse, its tone measured. It speaks not in riddles but in brief statements that suggest power without display. It claims to convey people back to the place they came from, though it offers no explanation beyond that. The snake is the only figure in the book who speaks directly of death, yet without fear or drama. Saint-Exupéry does not present it as evil or wise, only as a presence that adulthood often avoids: the fact of mortality, spoken plainly.

The Rose Garden

The prince comes upon a garden filled with roses. They look exactly like the rose he left behind on his own planet, the one he had cared for, protected, and struggled to understand. Until this moment, he believed that his own rose was unique. Faced with hundreds just like it, he feels something crumble. This scene captures a familiar shift in adult perception: when rarity is challenged, value seems to disappear. But Saint-Exupéry does not simply leave the thought there. The prince begins to understand that the rose’s value is not in its appearance but in the attitude of care that it has drawn out of him.

The Fox

The fox is the first figure on Earth who offers the prince something more than a reply: he asks to be tamed. Through their unhurried, intimate exchanges, the prince learns that relationships do not arrive fully formed. They are made slowly, through the passage of time, predictable routine, and devoted attention. The fox tells him, “You become responsible, forever, for what you have tamed.” Saint-Exupéry gives no further explanation because he doesn’t need to. The fox speaks to what adulthood often neglects: that connection is built on showing up, again and again, until the other is no longer interchangeable.

The Railway Switchman

The prince then meets a switchman who sorts trains, sending them left or right as they rush past. He explains that adults are always in motion, shifting between destinations, never satisfied with where they are. Only the children, he says, know what they’re looking for. The switchman speaks plainly, and the image speaks for itself: constant movement without direction, preoccupation mistaken for purpose. They move from one place to the next, repeating the motion long enough that the movement takes the place of the reason for starting.

The Merchant

The prince next meets a merchant who sells pills that quench thirst. He claims they save time—fifty-three minutes per week, to be exact. When the prince asks what someone might do with that time, the merchant has no answer. Saint-Exupéry presents this figure without irony. The merchant is efficient, precise, and uninterested in anything beyond the function of his product. It is not about water or need, but about removing the delay of stopping to drink. He treats time as something to be counted and saved, rather than spent with any attention. The prince, unmoved, says plainly that if he had fifty-three extra minutes, he would walk toward a spring of fresh water.

The Pilot

The pilot is the only character who shares time with the prince from the beginning of the book to its final lines. He crashes in the desert, preoccupied with repairing his engine, and at first sees the prince as a distraction. But gradually, his attention shifts. He begins to listen, to draw, to remember how he once saw the world. The pilot is not presented as fully lost or completely recovered, only as someone who has paused long enough to notice what he has overlooked. Saint-Exupéry gives him no title, no planet, no grand flaw, but a chance to remember. In the pilot, the book turns inward. The adult is no longer just a figure to examine but someone who must decide whether to see differently, even now.

Significant Objects

Some of the book’s most enduring figures are not characters at all, but objects. Each object draws out a habit of the mind, while some expose the patterns that harden our perception about reality. Others point to what still cuts through it. In this section, the focus shifts from who the prince speaks with to what he encounters, touches, and leaves behind. The questions that the book tries to explore remain the same: what do we still notice, what do we no longer see, and what have we trained ourselves to ignore?

The Baobabs

The baobabs begin as small shoots, harmless and easy to overlook. But if left alone, they grow large enough to tear the prince’s planet apart. That is why, each morning, he removes them—not out of fear, but through steady routine. Saint-Exupéry never says what they represent, but their meaning is clear. They stand for anything that becomes dangerous when ignored: thoughts left unexamined, duties postponed, small evasions that spread until they change everything. The danger is found in their subtle growth, achieved without having to rely on their initial size. What protects the prince’s planet is the rhythm of early attention: the removal of baobabs before their roots can take hold.

The Rose

The rose is the reason the prince leaves his planet and the reason he longs for home. She is proud, fragile, and often difficult to understand. She says little of what she means, and the prince, unsure of her feelings, leaves in confusion. Only later (because of distance, by virtue of remembrance, and the fox’s lesson) does he begin to understand her. Saint-Exupéry does not idealize the rose but draws her with restraint. What matters, as the book implies, is that the prince’s attachment to the rose does not come from her nature or being, but from the time he spent looking after her, even when he didn’t know why.

The Well

In the final pages, the prince and the pilot search for water and find a well in the desert. It is plain and unmarked, with no explanation for why it is there. The prince drinks and says the water feels different. What gives it its quality is not the source, but the time that came before it—the walking, the silence, the presence of another person. Saint-Exupéry does not tell the reader what to make of the well. He leaves it in place, devoid of any meaning; it is simply something found after moments of waiting, noticed, and remembered without being explained.

The Wall

Near the end of the story, the prince meets the snake again beside a low stone wall. He asks the pilot to leave him there, saying it will look like he has died. The wall marks the boundary between what can be explained and what must simply be accepted. Saint-Exupéry gives no clarity about what happens next. The pilot goes back the next day and finds no trace of the prince; even the snake is gone. There is no further revelation or explanation; what remains is the wall where he last stood. The wall does not confirm anything, yet it fixes the moment in place. It becomes the last point of contact between what was shared and what cannot be reached again.

The Stars

The stars appear throughout the book, but they change meaning as the story unfolds. To the businessman, they are things to count and own. To the pilot, they are part of the sky he once used to navigate. But to the prince, they become something else entirely. Before he leaves, he tells the pilot to look at the stars and remember his laughter. They will not explain anything; they will simply be there. Saint-Exupéry closes with that shift: the stars remain unchanged, but they no longer serve as objects to measure or name. They mark the place where something was once understood and might be again if looked at long enough.

Closing

The Little Prince is often read as a book that reminds us how to be young again. That reading is too narrow. Because the book reveals a stifled crisis at the heart of modern adulthood: attention grows shallow, usefulness becomes the only standard, and we learn to overlook what does not lead to a result. Disenchantment does not arrive suddenly. It builds through habits that reward speed, control, and measurable success, until wonder no longer feels natural.

This book urges a different discipline. Look closely at what cannot be measured. Give time to those who offer nothing in return. Speak with the patience that the fox demands and tend to the “baobabs” before they harden into obstacles. Resist the impulse to translate every value into productivity or gain. Allow beauty, conversation, and care to exist without an agenda. Remember that looking at the stars without seeking any explanation is not idleness; it is an act of recovery.

The gaze of a child is attentive and free from the burden of indifference that accumulates with age. When attention is intentional, the ordinary becomes mysterious again, and the presence of another gains more depth. Disenchantment is not fixed; only ingrained habit makes it familiar. In reclaiming these habits, adulthood no longer settles for efficiency alone—it reopens the possibility that what matters most may lie in what we learn to notice.

In reading this book, what Saint-Exupéry leaves behind is not a refuge for nostalgia but a set of instructions for living. The task is to look again, and to keep looking, until the familiar grows strange enough to be seen. In that act, the adult and the child meet—the adult bringing patience, the child renewal. The desert is still vast, but the well is still there for those who remember to search for it.

Further Reading

‘The Little Prince’ Comes of Age by Emma Kantor, Publishers Weekly

On the True Essence of Man: An Analysis of The Little Prince by Miftah Amir, economica.id

‘All grown-ups were once children’: the 15 top Le Petit Prince quotes by Marianne Tatepo, The Guardian

Why do adults consider The Little Prince such a great book? on Reddit