Explore This Topic

- Choosing a Narrative Structure: A Writer’s Blueprint

- Three-Act Structure: Components and Functions

- The Hero’s Journey: Mapping Transformational Arc

- The Fichtean Curve: Structuring for Unrelenting Momentum

- The Seven-Point Structure: Reverse-Engineering Your Plot

- Freytag’s Pyramid: The Structure of Tragedy

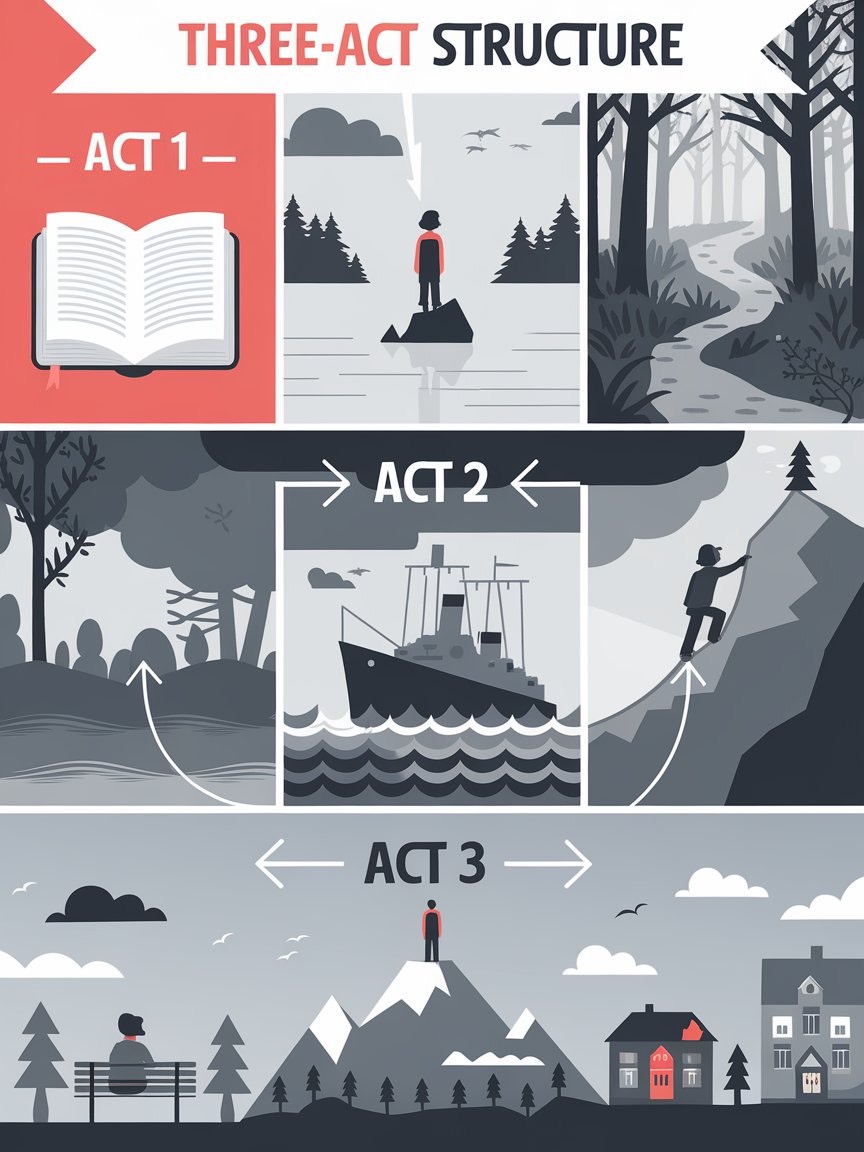

A functional story is a chain of cause and effect. The three-act structure provides the blueprint for forging this chain, ensuring each major story event forces the next. This model solves the writer’s core problem of escalation: how to move a narrative from a stable beginning, through compelling conflict, to an inevitable and satisfying end.

The value of this narrative structure is technical, not prescriptive. It does not dictate what must happen but creates a test for narrative logic. In this structure, each act addresses a specific structural question, with the aim of transforming the premise into a consequential plot.

Act One: Installing the Lever

Act One (Setup) engineers the story’s foundational pressure. Its function is to destabilize a status quo and impose a new, inescapable objective on the protagonist. This is achieved through three precise narrative components that transition the character from a state of merely “existing” to a state of “being compelled.”

- The Operating Tension: This is the specific, unstable condition that the narrative will exploit. It refers to the active flaw or latent conflict in the story’s world, which is more than just its setting. In Brit Bennett’s The Vanishing Half (2020), the tension is the return of Desiree Vignes to her oppressive hometown of Mallard, a community defined by its light-skinned Black hierarchy. Her arrival, which follows her flight from an abusive marriage, immediately reignites the central, unresolved mystery: the disappearance of her identical twin, Stella. The status quo is a powder keg awaiting a spark.

- The Catalytic Choice: The protagonist must make an active decision that locks them into the central conflict. This transforms an external circumstance into a personal commitment. In J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit (1937), the inciting incident is the arrival of the dwarves, but the act’s pivotal turn comes the next morning when Bilbo actively runs out of his house to join them at the Green Dragon Inn. Only when Gandalf presents him with Thorin’s note and he consciously chooses to abandon his comfortable home does the problem move from his doorstep and become his direct, personal responsibility. He is no longer a bystander but a participant.

- The Narrative Imperative: The act concludes by establishing a clear, actionable objective established directly by that choice. This imperative drives the protagonist into the unknown of Act Two. For Desiree, it is the dual goal of rebuilding her life in Mallard while being forced to confront the ghost of her sister. For Bilbo, it is the explicit mission to travel to the Lonely Mountain and help reclaim the dwarves’ treasure. The first act’s work is complete when the protagonist crosses a threshold, physical or psychological, with a defined goal that sets the chain of cause and effect in irreversible motion.

Act Two: Intensifying the Pressure

Act Two (Confrontation) systematically tightens the pressure established in Act One. Where the first act installed a lever, the second act engages the protagonist in a sustained struggle, raising the cost of their goal and compelling them to evolve from a reactor to a strategic actor.

- Complication and Escalation: The protagonist’s initial plan for achieving their Narrative Imperative meets immediate, logical resistance. Each complication should test a different facet of the core problem to avoid repetitive conflict and to deepen the story’s central argument. In Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (1813), Elizabeth Bennet’s objective after the Meryton assembly (to understand and navigate her social world) is thwarted not by one event, but by a series: Mr. Darcy’s insult, his interference in Jane’s romance with Mr. Bingley, the deceptive history provided by Mr. Wickham, and the public disgrace of her sister Lydia. Each obstacle challenges a different aspect of Elizabeth’s judgment, forcing her to continually reassess her situation.

- The Reversal: A pivotal event near the story’s center fundamentally redefines the conflict for the protagonist, often inverting their goal or redefining the antagonist. This is not a simple setback but a revelation that raises the stakes from external pursuit to internal or moral reckoning. In Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go (2005), the students’ growing awareness of their fate as clones culminates when their purpose as organ donors is made explicit. The narrative tension shifts from the mystery of “What is Hailsham?” to the inescapable tragedy of “How do we live with this knowledge?” Their goal changes from seeking answers to seeking a possible, fleeting deferral.

- The Crisis Point: This is the final, major obstacle before the climax. All preceding complications funnel the protagonist into a situation where all remaining choices are bad, each requiring the sacrifice of a core value. The decision made here, such as which value to abandon or which path to take, defines the protagonist’s ultimate priority and directly enables the final confrontation. It is the point of no return.

Act Three: Executing the Consequence

Act Three (Resolution) resolves the chain of cause and effect initiated in Act One and tightened in Act Two. Its function is to execute the definitive, irreversible action that severs the story’s core tension, delivering a conclusion that feels both surprising and inevitable.

- The Conclusive Action: This is the event that makes the final resolution unavoidable. It is the direct, often violent, outcome of the protagonist’s Crisis Point decision. In F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925), the climactic action is George Wilson’s murder of Gatsby. This is not a random act but the logical endpoint of the chain of deceptions (Tom’s infidelity, Gatsby’s fabricated identity, Daisy’s reckless choice) set in motion throughout the novel. The tension of Gatsby’s dream is permanently severed.

- The Resultant State: Following the Conclusive Action, the narrative must show the new, permanent condition it has established. This demonstrates the cost and consequence of the entire plot, moving beyond simple closure to show lasting change. In Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (1960), the climax is the attack by Bob Ewell and Boo Radley’s intervention. The true resolution is the resultant state: Scout walking Boo home and seeing her neighborhood from his porch. This moment crystallizes the novel’s moral argument about empathy and justice, showing how the events have fundamentally altered her view of the world.

The structural engine has completed its cycle: a lever was installed, pressure was applied and intensified, and the built-up tension has been decisively released, leaving the world and its characters irrevocably changed.

The Three-Act Structural Engine

| Core Narrative Function | Key Technical Components & Their Role | Literary Example (Component) |

|---|---|---|

| ACT ONE: Setup — Installing the Lever To engineer foundational pressure and impose a new, inescapable objective. | ||

| Function: To transition the protagonist from a state of ‘existing’ to ‘being compelled’. |

| Example: In Brit Bennett’s The Vanishing Half, Desiree’s return to Mallard creates the Operating Tension that reignites the central mystery. |

| ACT TWO: Confrontation — Intensifying the Pressure To systematically tighten pressure and compel strategic evolution. | ||

| Function: To raise the cost of the goal and transform the protagonist from reactor to actor. |

| Example: In Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth Bennet’s misunderstandings act as Complications that systematically test her judgment. |

| ACT THREE: Resolution — Executing the Consequence To sever the core tension and show permanent change. | ||

| Function: To deliver an inevitable conclusion that resolves the story’s foundational tension. |

| Example: In F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Gatsby’s murder is the Conclusive Action, the direct result of the story’s chain of deceptions. |

Further Reading

Beginning, Middle, and End: A Simple Guide to Story Structure for Writers by Johnny Shaw, Storius Magazine

MEET THE READER: My Defense of the Three-Act Structure by Ray Morton, Script

Thoughts on the 3 act structure? on Reddit