Explore This Topic

To read a poem well is to attend to its construction. This attention directs the reader to the pattern of stresses, the placement of pauses, the selection of images. These elements constitute the materials of poetic thought. Operating as a constitutive logic, they combine to form a specific perspective. The poem’s theme is the understanding produced by this perspective. This article traces that process, by analyzing specific works, from their technical choices to their thematic conclusions.

Poetic Machinery

This process depends on understanding poetic technique as a form of cognition. The technical elements of a poem function as its cognitive instruments. Each element governs the reader’s perception before interpretation can begin. For example, the poem’s meter establishes its temporal logic—a regular iambic pentameter imposes an order of anticipation and fulfillment; by contrast, a broken or inconsistent meter introduces uncertainty into the very rhythm of reading.

Furthermore, lineation controls spatial and temporal emphasis. It dictates where a thought pauses or accelerates. An end-stopped line presents a complete unit of sense, a purposive step. On the other hand, an enjambed line propels the reader forward, creating a tension between syntactic continuity and visual interruption. The line break becomes a gesture of continuation or separation.

Imagery, however, transforms the poem’s concepts into perception. A recurrent or central image does not illustrate an abstract theme; it becomes the tangible medium in which the theme is considered. The reader confronting mortality in John Donne’s “Holy Sonnet X” encounters not an argument but a direct address: “Death, be not proud.” The image personifies the concept, making it an entity for confrontation. The image focuses intellectual energy into a sensory field that can be returned to, its facets examined through repetition and variation.

Analytical Catalogue

The following analyses apply the principle that a poem’s technical elements are the materials of its thought, tracing this process from technical choice to thematic clarity. Each examines how specific decisions of meter, line, and image combine to form the perspective that yields the poem’s definitive theme.

Time and Impermanence

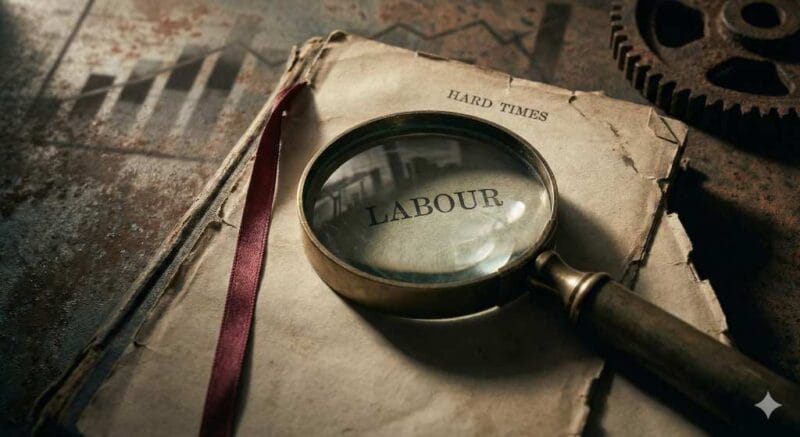

Robert Herrick’s “To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time”

The theme of time’s passage is performed by the poem’s meter and imperative mood. The steady, marching iambic tetrameter (“Gather ye rosebuds while ye may”) creates a rhythm of irreversible forward motion. This metrical inevitability is heightened by a strict rhyme scheme that closes each stanza with decisive finality. The poem’s dictum, “be not coy,” gains its authority from the rhythmic press of the lines that carry it, a rhythm that eliminates pause or hesitation. The poem’s steady meter and final rhymes frame its implicit advice (to act now) as an inevitable command.

Isolation and Perception

Emily Dickinson’s “I heard a Fly buzz – when I died –”

Dickinson constructs a theme of dissociated consciousness through abrupt grammatical marks and sparse imagery. The poem’s defining technique is its use of dashes, wherein they break syntactic continuity and mimic the faltering of attention at the moment of death. The central image of the “Fly” functions as a focal point for a consciousness narrowing from the grand expectation of “the King” to a mundane sensory detail. The poem’s broken form executes the thematic separation between the self and the world. This technique renders isolation a perceptual event distinct from an emotional state.

Myth and National Identity

William Butler Yeats’s “Easter, 1916”

Yeats examines the transformation of individuals into national myth through a controlled tension between irregular and trance-like repetition. The poem’s refrain, “A terrible beauty is born,” operates as a technical and thematic pivot. Its repetition marks rhythmic sections, each time applying to a new facet of the event, such as personal loss, political change, and historical legacy. The refrain’s persistent presence formalizes the process of myth-making, where complex reality is gradually solidified into a memorable, haunting phrase. The theme emerges from this formal mechanism of rhythmic, incantatory consolidation rather than from the description of the rebels.

This analytical method, tracing the theme to its technical origins, provides a model for reading beyond poetry. For the theoretical framework that defines theme as a narrative mechanism, see the central guide, Themes in Literature: A Definitive Guide.

Further Reading

Finding the Subject by Poetry Foundation

Identifying Themes in Our Poems by Sara Letourneau, DIY MFA