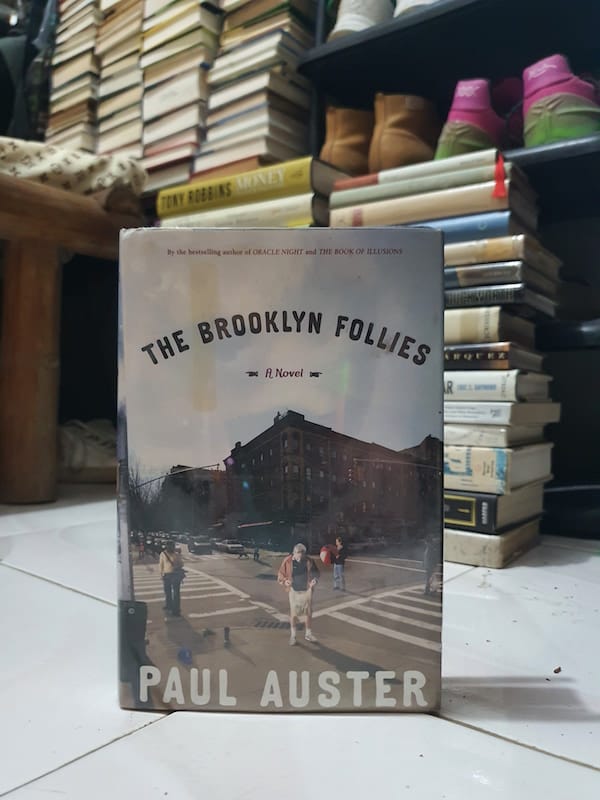

Paul Auster’s The Brooklyn Follies (2005) is a textbook example of a metafictional novel. The protagonist, Nathan Glass, is a cynical 59-year-old lonesome man who has undergone a tragic turn of events; he is a cancer survivor who is writing his own memoir. Nathan has relocated to Brooklyn and has come for one reason only: to die peacefully.

At the start of the novel, we like Nathan right away because he’s generous and wide-eyed about the newfound place he’s currently in, while at the same time being vulnerable, snobbish, and critical. In the story, events and coincidences happen at random and out of nowhere. While he says he doesn’t intend to stay in Brooklyn for one year, the city’s charms quickly reenergize him. Nathan embarks on a life-affirming trip with Tom and Harry as his unusual companions, encountering bizarre experiences and stunning insights along the way.

Occasionally, Auster’s literature has been panned for being too unbelievable. Because of his focus on chance, the reader will have to exercise a great deal of “suspension of disbelief” in order to follow along. While being concerned about humanity’s ignorance and helplessness is admirable, Auster has a tendency to overuse reminders of the arbitrary nature of life. Despite the fact that its tropes and foibles are predictable, the quality of its writing is undeniable. It is Nathan who warns us not to be blinded to life by either despair or laziness.

Auster’s novel is a celebration of human stupidity and pulls on Nathan’s and other people’s experiences to demonstrate to its readers its message. The book celebrates the beauty of life which is in stark contrast to its depressing conclusion. The ending has such a tremendous impact on the story that precedes it that it nearly begs for a re-read not only to understand what really happened but to savor the kitsch moments that eventually come together under the tapestry of Auster’s linguistic beauty.

Selected Passage with Analysis

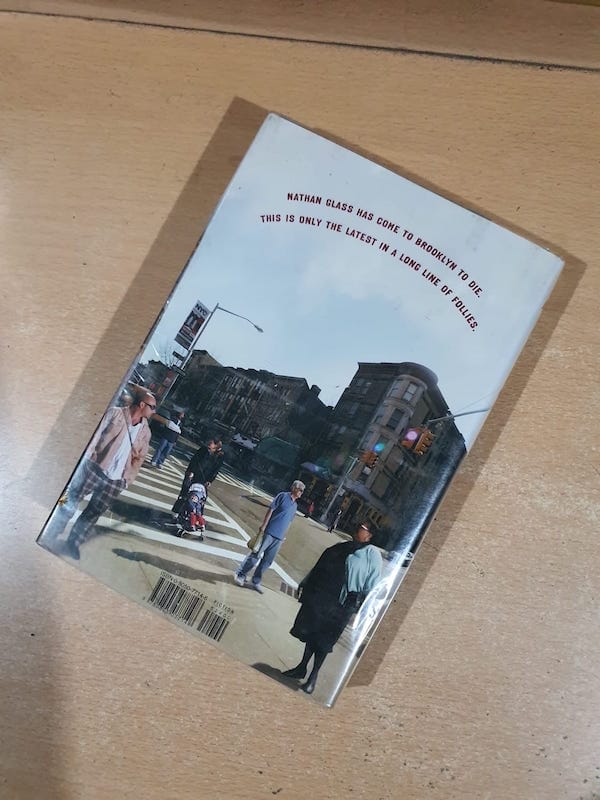

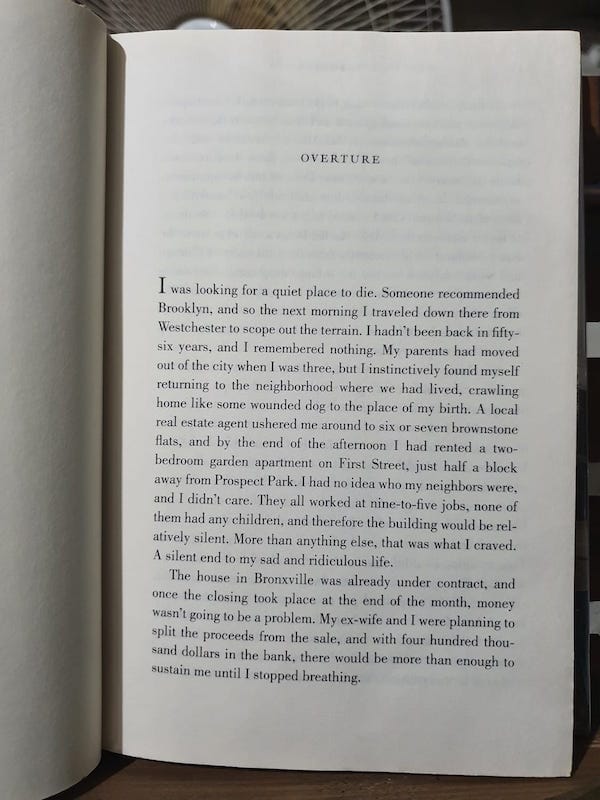

I was looking for a quiet place to die. Someone recommended Brooklyn, and so the next morning I traveled down there from Westchester to scope out the terrain. I hadn’t been back in fifty-six years, and I remembered nothing. My parents had moved out of the city when I was three, but I distinctively found myself returning to the neighborhood where we had lived, crawling home like some wounded dog to the place of my birth. A local real estate agent ushered me around to six or seven brownstone flats, and by the end of the afternoon I had rented a two-bedroom garden apartment on First Street, just half a block away from Prospect Park. I had no idea who my neighbors were, and I didn’t care. They all worked at nine-to-five jobs, none of them had any children, and therefore the building would be relatively silent. More than anything else, that was what I craved. A silent end to my sad and ridiculous life.

Opening paragraph, The Brooklyn Follies by Paul Auster

Paul Auster’s passage delves into themes of solitude, despair, and a reluctant search for belonging. The protagonist’s journey to Brooklyn reflects his resignation, as he seeks a quiet place to confront the end of his life. This return to his birthplace, despite his lack of memory of it, suggests a subconscious longing for closure or a connection to origins. The contrast between his physical return and emotional detachment highlights his existential despair, as he views life and its culmination with a sense of futility.

The protagonist’s emotional and psychological state is marked by profound despondency and withdrawal. He views himself as a “wounded dog,” emphasizing his vulnerability and the instinctual nature of his return to Brooklyn. His disinterest in neighbors or community, coupled with his craving for silence, underscores his isolation and desire for disengagement from the world. Auster’s tone balances the bleakness with a touch of self-aware irony, particularly in the description of life as “sad and ridiculous,” which subtly tempers the heaviness of the passage.

Stylistically, Auster employs retrospective narration and precise, unembellished language to reinforce the protagonist’s resignation. The imagery of the “wounded dog” crawling home evokes both pathos and inevitability, while the detailed descriptions of Brooklyn create a vivid sense of place. This juxtaposition of internal despair against the solidity of the external world enhances the passage’s somber yet introspective tone.

Further Reading

The Brooklyn Follies, by Paul Auster by Eric Homberger, Independent

A reading of The Brooklyn Follies through the lens of autofiction by Marie Thevenon, Allocataire-monitrice – Université Stendhal – Grenoble 3

An Aspect of Contemporary Dystopia: An Analysis of Paul Auster’s The Brooklyn Follies by Kuniko Egaitsu, PDF file

The Reinvention of Paul Auster by Chauncey Mabe, South Florida Sun-Sentinel