Explore This Topic

- Literary Theory: A Guide to Critical Frameworks

- Structuralism in Literature: Core Concepts and Analysis

- Reader-Response Theory and the Dynamics of Community Interpretation

- Poststructuralism: A New Approach to Knowledge

- The Death of the Author: Demolition of Author-Centric Criticism

- Marxist Criticism: Theory of Class and Ideology in Literature

- Feminist Literary Criticism: History, Theory, and Analysis

- Postcolonial Criticism: Theory and Analysis

- Ecocriticism: Theory, History, and Literary Analysis

- New Historicism: Reading Literature in its Cultural Moment

- Psychoanalytic Criticism: The Unconscious in the Text

Psychoanalytic criticism reads literature as an expression of unconscious processes. It proposes that the dynamics of the unconscious mind, such as repressed desires, internal conflicts, and formative traumas, manifest symbolically within literary language, character, and narrative structure. The critic’s task is to diagnose these latent psychic formations, treating the text as a network of symbols and defenses that requires decoding. The critical operation analyzes the text as a symbolic system where unconscious material achieves disguised expression.

The practice of psychoanalytic criticism involves analyzing the psychic economy of a text. It traces the operations of desire, identifies mechanisms of repression and sublimation, and interprets symbolic imagery. The objective is to uncover the unconscious logic that organizes the narrative, providing a vocabulary to analyze literary production as a process analogous to dream-work, where latent content undergoes distortion to become the manifest story.

Theoretical Origins: From Freud to Lacan

Psychoanalytic criticism derives its theoretical foundation from the work of Sigmund Freud, who established the core concepts of the unconscious, repression, the Oedipus complex, and dream analysis. For Freud, artistic creation functioned as a form of sublimation, a channeling of libidinal energy into socially acceptable creative work. The author’s psyche, and by extension the fictional worlds they create, become a primary object of analysis.

This foundation underwent a radical linguistic turn with Jacques Lacan. Lacan reformulated Freudian theory through structuralist linguistics, arguing that “the unconscious is structured like a language.” His concepts of the Mirror Stage, the Symbolic Order (the realm of language, law, and culture), and the Imaginary (the realm of images and identifications) provided new tools for literary analysis. For Lacan, the subject is constituted by and within language, and literature reveals the gaps, desires, and lacks inherent in this condition.

Theorists like Julia Kristeva further expanded the field with concepts such as the semiotic chora, a pre-linguistic dimension of rhythmic, bodily drive energy that pressurizes symbolic discourse.

Core Tenets: Desire, the Symbolic, and the Subject

Psychoanalytic criticism operates through several interconnected principles.

- The Analysis of Desire and Lack: A primary tenet involves tracing the movements of desire within the text. Desire, understood as a perpetual lack or want, drives narrative action and character motivation. The critic examines what characters desire, how that desire is frustrated or displaced, and how the narrative itself is structured around an unattainable object (the Lacanian objet petit a).

- The Symbolic Order and the Unconscious: The theory analyzes how the text engages with the Symbolic Order—the overarching system of language, social norms, and paternal law. Characters’ struggles often represent a conflict with this order, and their speech can reveal the pressures of the unconscious breaking through the conscious discourse. Symptoms, slips, and repetitive imagery are read as manifestations of repressed material.

- The Constitution of the Subject: Psychoanalytic criticism investigates the formation of literary subjectivity. It applies models like the Oedipus complex or the Mirror Stage to character development by examining processes of identification, alienation, and the assumption of a social role. The text becomes a stage for the drama of subject-formation, exploring how the individual “I” emerges through and against familial and social structures.

Application: Reading as Diagnosis

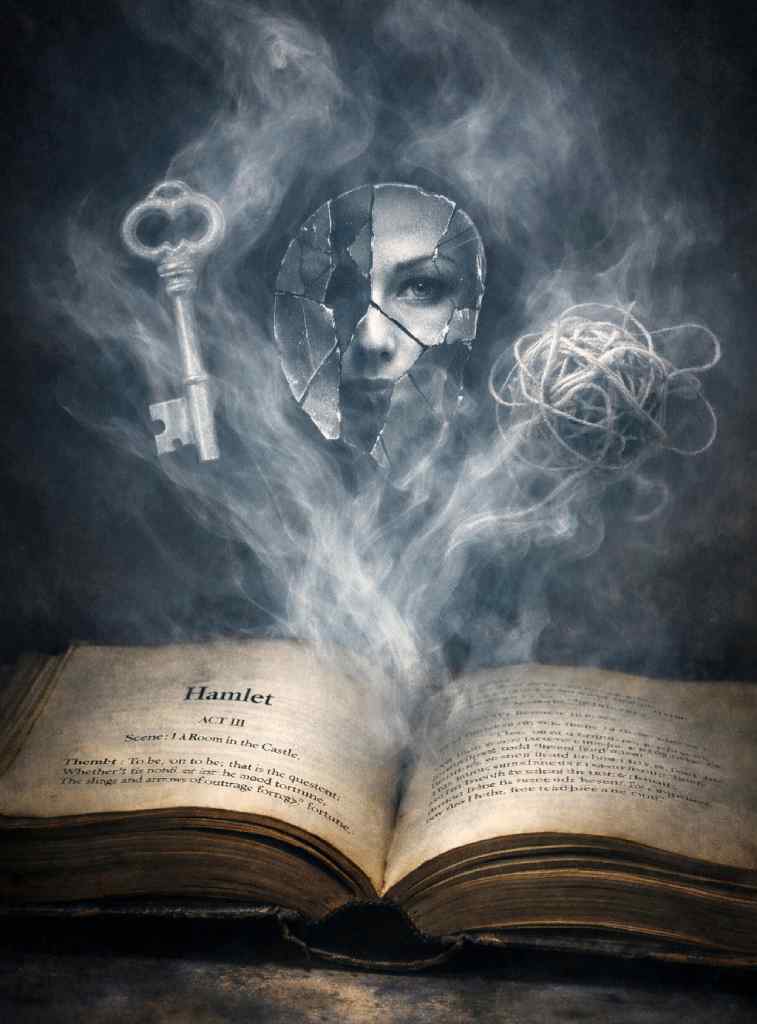

A psychoanalytic reading demonstrates how these principles transform interpretation. Consider an analysis of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. A traditional reading focuses on revenge and indecision. A psychoanalytic critic, following Freud and Ernest Jones, locates the core conflict in Hamlet’s unresolved Oedipus complex. His inability to act against Claudius stems from an unconscious identification: Claudius has fulfilled Hamlet’s own repressed childhood wish to kill his father and possess his mother.

Furthermore, Hamlet’s disgust with female sexuality, expressed toward Ophelia and Gertrude, projects his own guilty desires. The play’s symbolic imagery (the ghost, the poisoned ear, the Yorick skull) gives form to repressed familial trauma and death anxiety. Such a reading recalibrates the text from a Renaissance tragedy to a universal drama of psychic conflict.

Expansion and Critique: Beyond the Author’s Psyche

Psychoanalytic criticism has significantly expanded beyond its initial focus on authorial biography. Later schools maintained the core interest in unconscious processes but redirected the analytical object. Object relations theory, developed by Melanie Klein and D. W. Winnicott, shifted emphasis from Freudian drive theory to the formative role of early interpersonal relationships. This provided critics with tools to analyze literary representations of maternal spaces, transitional objects, and the dynamics of attachment and separation within narrative structures.

These expansions generated substantive internal critiques, particularly regarding gender. Feminist psychoanalytic critics, most notably Julia Kristeva and Luce Irigaray, rigorously re-examined the foundational models of Freud and Lacan. They challenged the presumed universality and phallocentrism of concepts like the Oedipus complex and the Symbolic Order, developing alternative theories of feminine subjectivity and a maternal semiotic that operates within and against patriarchal discourse. This critique transformed the field by insisting on the centrality of sexual difference to psychic and textual analysis.

Consequently, psychoanalytic criticism today operates as a diverse and self-critical discipline. While its deterministic focus on authorial neurosis has been largely superseded, its enduring influence resides in its capacity to analyze desire, identity, and symbolic language. The method remains vital for examining the complex negotiations between the subject and social law, the presymbolic and the symbolic, that constitute the deep structure of literary narrative.

By investigating the unconscious desires of characters, authors, and cultures, this theory applies a deep psychological framework to interpretative acts, one of several major frameworks compared and contrasted in Literary Theory: A Guide to Critical Frameworks.

Further Reading

Psychoanalytic Fiction Writers by Jeffrey Berman, TAP Magazine

Which Type of Theory is Psychoanalytic Criticism and Why by Hasa, Pediaa

The Idea of a Psychoanalytic Literary Criticism [PDF file] by Peter Brooks, web.english.upenn.edu