Explore This Topic

- Characterization in Literature: Types, Techniques, and Roles

- Character Arc: Transformative Journey in Fiction

- Character Development: Key Questions for Writers

- Character Analysis: Protagonists and Antagonists Explored

- Character Complexity in Literary Fiction

- Foil Character

- 10 Examples of Literary Archetypes

- Raskolnikov: A Character Analysis

Character development is the foundational act of invention that precedes narrative. It involves constructing a fictional psychology, a coherent system of memory, desire, and apprehension. This internal system functions as the source material for all subsequent portrayal.

The questions presented here serve as a framework for that construction. They are designed to define a character’s interior world, moving past general biography to establish operational drivers. The substantive definitions these questions produce become the necessary groundwork for implementing techniques of characterization and for launching a credible character arc.

Origin and Backstory

A character’s history operates as a formative causal chain. The person who enters the story is a product of that chain. The writer must define this history with exact detail to produce credible behavior.

Diagnostic Questions:

- What formative events, prior to the story’s start, have defined this character’s worldview?

- What central relationships from their past (familial, platonic, adversarial) continue to exert influence?

- What specific accomplishment or failure remains most significant to them now?

- What explicit or implicit cultural, social, or economic forces have formed their circumstances and values?

The answers to these questions must construct a coherent past that motivates present action. For instance, a character’s acute distrust of institutions could originate from a childhood betrayal by a trusted authority figure. This single historical fact then drives specific, credible choices within the plot. This functional link ensures the character’s history emerges through their present decisions, not through explanation. Furthermore, a well-defined past establishes the essential starting point for the character’s journey, providing the necessary baseline from which their transformation is measured.

Desire and Motivation

A character’s desire is the engine of plot; motivation, meanwhile, is the logic of that desire—the internal, often unspoken reason a goal holds importance that is non-negotiable. Clear and specific motivation transforms a character from an actor following a script into an agent whose choices feel necessary and true.

Diagnostic Questions:

- What is this character’s primary, actionable goal at the story’s outset? What do they believe will solve a core problem or fulfill a fundamental lack?

- What deeper, perhaps unconscious, psychological need does this surface goal attempt to address? (e.g., the desire for wealth might mask a need for security or validation).

- What are they willing to sacrifice, compromise, or risk to achieve this goal? What line will they not cross?

- How does this central desire come into direct conflict with the desires of other key figures?

A protagonist who seeks a promotion (surface goal) to gain a rival’s respect (deeper need) will make different choices than one who seeks it for financial power. This distinction in motivation determines their actions when faced with an ethical compromise. The friction between such clearly defined and opposing desires generates authentic dramatic conflict. The subsequent evolution (or corruption) of that character’s motivation frequently charts the progression of their personal journey.

Flaw and Internal Conflict

A compelling character is defined not by competence alone but by a foundational flaw. This flaw, whether a habitual weakness, a damaging bias, or a rigid belief, creates the internal friction that makes their journey necessary and difficult. It is the primary obstacle they must engage, whether to overcome, succumb to, or reconcile with.

Diagnostic Questions:

- What central, habitual weakness impedes this character? Is it pride, cowardice, envy, a need for control?

- What inaccurate or limiting belief about themselves, others, or the world does they hold? How does this belief shield them from a painful truth?

- How does this flaw specifically obstruct their primary desire or goal?

- In what recurring situations or relationships does this flaw manifest most destructively?

For example, a detective’s flaw might be a distrust of protocol that borders on contempt for the system. This flaw could lead them to withhold vital evidence, creating a critical plot complication. More importantly, it forces a continuous internal struggle between their goal (solving the case) and their nature (operating outside the rules). This struggle between desire and flaw is the core substance of internal conflict. The character’s relationship to this flaw (whether they recognize it and how they choose to engage with it) forms the central mechanism of their psychological growth.

Worldview and Voice

A character’s worldview is the lens through which they interpret events; their voice is the distinct verbal expression of that lens. Together, they determine what a character notices and how they articulate it, making the narrative perspective uniquely theirs.

Diagnostic Questions:

- What is this character’s fundamental belief about how the world operates? Is it inherently just, chaotic, or indifferent?

- What principles, morals, or personal codes do they claim to live by? Where do their actions betray these codes?

- How does their socioeconomic background, education, and culture filter their perception of people and events?

- What is the characteristic rhythm, vocabulary, and syntax of their speech? How does their internal monologue differ from their spoken dialogue?

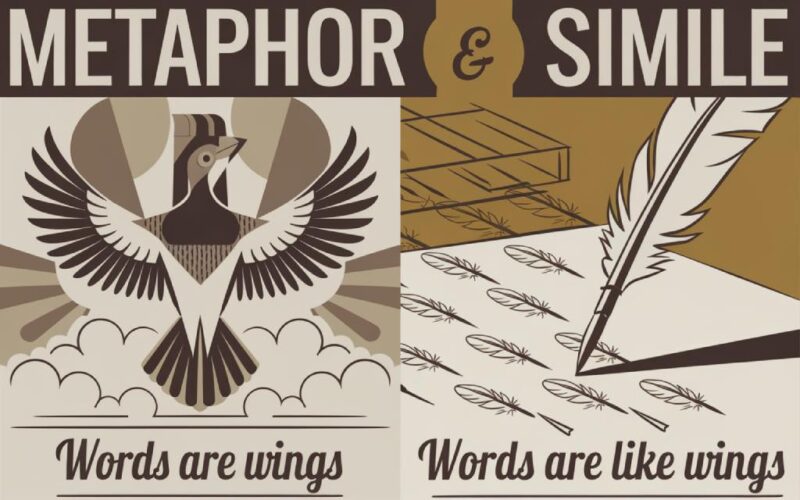

A cynical character who believes the world is a selfish competition will narrate a charitable act as calculation, not kindness. Their voice might be clipped, sarcastic, and rich with transactional metaphors. This consistent perspective achieves character verisimilitude. When this worldview is challenged by events (e.g., forcing the cynical character to accept genuine altruism), that conflict becomes the catalyst for profound change. Furthermore, the contrast between the worldviews of different characters is a primary source of dialogue-driven tension.

###

The questions presented here are not an endpoint but a point of origin. They are instruments for constructing the internal logic of a fictional being. The answers they yield, e.g., a specific history, a foundational flaw, or a coherent worldview, compose the essential blueprint of a character.

This blueprint is the prerequisite for all effective narrative execution. It supplies the specific material required for the techniques of characterization, by turning abstract concepts into actionable craft. Furthermore, this defined starting condition establishes the necessary foundation from which a credible and meaningful character arc must launch, providing the baseline against which all transformation is measured.

The work of character development concludes when the writer can reliably predict how this constructed person will act, react, and interpret their world under any narrative pressure. At that point, the character is ready to enter the story.

Further Reading

Who’s Your Favorite Character? by Ann E. Lowry, Writer’s Digest

The Heart of Fiction: Character versus Plot by Michelle Barker and David Brown, The Darling Axe

10 Famous Literary Characters Based on Real People by Stacy Conradt, Mental Floss

Is it possible to write a novel without character development, and still be a good story? on Quora