My Reading Note

My most difficult and rewarding reading experience was with William Faulkner’s Light in August. The novel did not flow in a clean line; it was a dense, knotted thicket of voices and timelines, circling a central event. I felt lost, unable to locate a stable perspective from which to view the story.

The analysis of narrative often proceeds by cataloguing its surface features—first-person, third-person limited, unreliable. These are useful labels, but they describe effects, not causes. They name the destination, not the machinery of the journey. To understand more precisely the machinery of narrative, we need to separate the engine’s parts.

Faulkner’s technique forced me to do what simple terms like “third-person omniscient” couldn’t describe: I had to actively construct the narrative lens, moment by moment.

This article presents a new diagnostic model for analyzing advanced narrative technique: The Narrative Triangle. This model argues that every narrative moment results from the dynamic interaction of three technical components: Narrative Voice (who speaks), Focalization (who perceives), and Free Indirect Discourse (the stylistic bridge between them). This triad forms the architecture of perspective.

Three Core Narrative Techniques: The Vertices of the Triangle

The model’s first function is to isolate and define the three elements that compose narrative perspective. This isolation addresses the tendency to treat these parts as a single entity.

1. Narrative Voice: The Source of Discourse

Narrative voice is the grammatical and rhetorical source of the story. It answers the question: Who is speaking? This is the component traditionally labelled as first, second, or third person. A first-person voice (“I”) implies a character-speaker within the story world. A third-person voice (“he,” “she,” “they”) implies a narrator external to it. The voice establishes the foundational contract with the reader, which is the basic grammatical rules of the narrative world. It is the telling position.

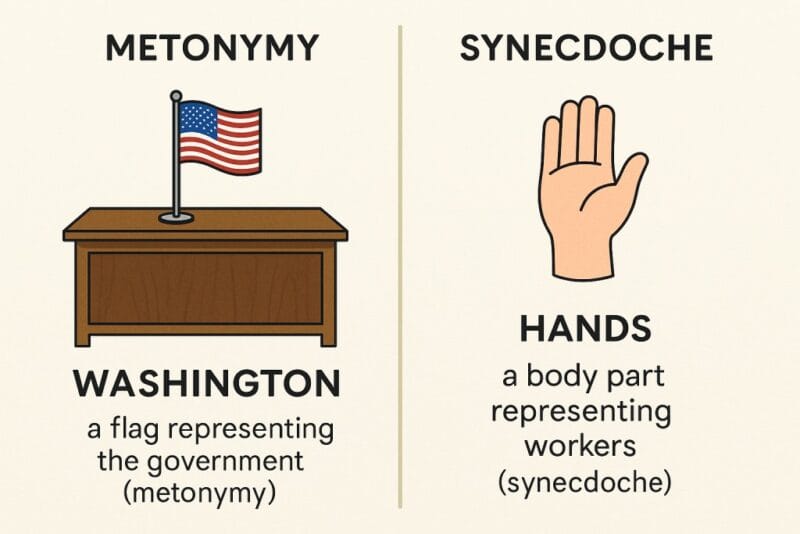

2. Focalization: The Lens of Perception

Focalization is the model of perception. It answers the question: Through whose consciousness is the story filtered? This is distinct from voice. A third-person voice can be coupled with internal focalization on a single character, reporting only what that character sees, knows, and feels. This same third-person voice could instead employ zero focalization, possessing a godlike, unlimited perception of all characters and events. Focalization controls the scope and bias of information. It is the seeing position.

This is where casual analysis fails. Calling a passage “third-person limited” is a vague description. Identifying it as “third-person voice with internal focalization on Character X” is a more precise diagnosis of its narrative mechanics.

3. Free Indirect Discourse: The Technique of Synthesis

Free Indirect Discourse (FID) is the primary stylistic technique for merging voice and focalization. It exists in the grammatical space between direct thought (“He thought, ‘I am lost.'”) and purely external narration (“He was lost.”). In FID, a third-person narrator’s voice absorbs the diction, syntax, and emotional register of a character’s consciousness: “He was lost. Where was the path? This was hopeless.” FID is the method by which a narrative can maintain a third-person voice while achieving the deep internal access of first-person focalization.

This article is my attempt to diagram that system, to build a model that explains the perspective’s nature and its operation by separating its core components: the voice that speaks, the consciousness that perceives, and the technique that merges them.

The Model as a Dynamic System

The power of the Narrative Triangle is in their interaction, not in its vertices alone. The components are dynamic coordinates, not fixed settings. A shift in one necessitates a shift in the others, and this reconfiguration is the source of the narrative effect.

In retrospect, my frustration in reading Faulkner’s novel revealed that perspective is not a singular, preselected setting. It is a dynamic system.

The most common operation is the use of FID to narrow the gap between a third-person voice and a character’s internal focalization. This synthesis creates intimacy and irony. It achieves this without abandoning the flexibility of external narration. Conversely, a narrative can create distance by widening the gap. It does this by employing a third-person voice with external focalization. This technique denies access to any character’s mind, as in the detached, behavioral narration of some realist and noir fiction.

A first-person narrator typically presents a collapsed triangle: the “I” is the voice, the focalizer, and the source of the discourse, with FID being unnecessary. However, even here, the model clarifies complexity. The retrospective first-person narrator, like the older Scout in Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (1960), contains two focalizers, the experiencing child and the narrating adult. This situation creates a gap that FID-like techniques can navigate.

Methodological Scope and a Foundational Model

This analysis employs a structuralist-narratological model. It treats the narrative text as a system of functional components. The Narrative Triangle is a diagnostic tool within that system, used to isolate and describe the mechanism of perceptual and vocal control.

The analysis sets aside questions of authorial biography or reader psychology. Its object is the technical operation of the text itself. The model asks: What is the voice? What is the focalization? What technique governs the distance between them? How do shifts in this configuration create meaning?

A Case in Point: Light in August and the Unstable Triangle

Faulkner’s Light in August (1932) provides a masterclass in this dynamic reconfiguration. The novel employs a third-person voice, but its focalization is perpetually unstable. It does not simply “head jump” between characters—a practice that can exhaust and confuse the reader. Instead, it uses the triangle’s components to create a specific literary effect: the dispersal of a single, authoritative truth.

The narrative circles the story of Joe Christmas, a man haunted by the uncertain specter of his own biracial identity. Faulkner’s technique mirrors this internal and social condition. For pages, the focalization will rest internally with one character—say, the Reverend Gail Hightower, lost in his memories of the Civil War. The voice remains third-person, but through pulses of FID, we are submerged in the rhythms and obsessions of Hightower’s mind. Then, without a chapter break, the focalization detaches. It floats to another consciousness—Lena Grove, Byron Bunch, or into the collective gossip of the town of Jefferson. The voice remains constant, but the perceptual lens has shattered. We are not given a single truth but a collage of subjective, often contradictory, truths.

The “muddle” I felt as a reader was not confusion. It was the intended experience of a community’s collective prejudice and fear.

The Triangle as an Applied System

A Contrarian View: Against “Point of View” as a Unitary Choice

The prevailing discourse instructs writers to “choose a point of view.” The Triangle model reveals this to be a misleading simplification. One does not choose a point of view but instead configures a system. The choice is not between first and third person, but between countless possible alignments of voice, lens, and stylistic bridge. A writer configures the triangle; the resulting effect is what we later label “first-person limited” or “third-person omniscient.” This reframing redefines the writer’s task from choosing a fixed label to engineering a narrative mechanism.

Observed Patterns in Reader Engagement

The Triangle predicts reader experience. Configurations with a close alignment of voice and focalization (via FID) generate high intimacy and character alignment. Configurations with a wide gap (objective, external focalization) generate analytical distance and interpretive demand. The cognitive work of reading complex fiction is often the task of tracking subtle reconfigurations within the protagonist’s own triangle, as in novels of growing self-awareness.

The Foundational Link to Narrative Reliability

The Triangle is the prerequisite for a technical understanding of reliability. A narrator’s reliability is not a personality trait but a function of their position within the triangle. A first-person narrator (collapsed triangle) is inherently limited to their focalization; their potential unreliability is a condition of the design. An omniscient narrator (third-person voice with zero focalization) sets an expectation of total authority; its rare lapses are thus profound violations.

The model provides the coordinates for locating where, precisely, the narrative contract is vulnerable. The Narrative Triangle provides a unified framework for understanding sophisticated narrative technique.

Points of View: A Comprehensive Guide

Narrative Focalization: The Architecture of Point of View

The three articles from the archive provide the complete structural framework for the new model. “Points of View” establishes the foundational taxonomy of narrative modes, “Narrative Focalization” supplies the technical model that distinguishes seeing from speaking, and “Free Indirect Discourse” defines the primary technique for merging those two components. This article synthesizes these three pillars into an applied diagnostic system, transforming them from separate concepts into an integrated analytical tool.

Further Reading

Is James Joyce the Innovator of Modern Literature? by Miloš Milačić, The Collector

The Methods of Focalization in Short Stories by Carver, Hemingway, and Aidoo by Zahra S., Medium

Balancing the 5 Narrative Writing Modes by catehogan.com

What is the difference between a narrative voice and a point of view? on Quora