New Historicism is a method of literary criticism that emerged in the 1980s, primarily through the work of Stephen Greenblatt. It challenges the idea that literature exists in a vacuum, isolated from historical and cultural forces. Instead, it proposes that every literary text is formed by the social, political, and economic conditions of its time, and that these same texts also participate in determining those conditions.

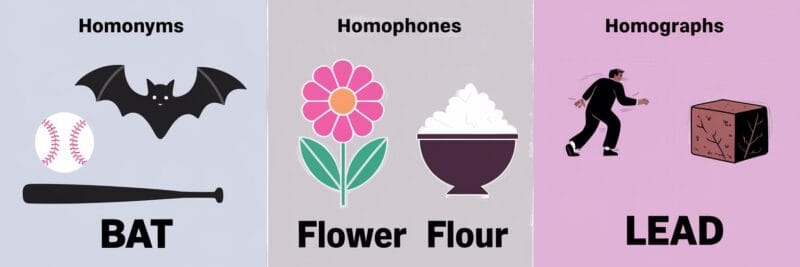

Unlike earlier historicist models, which treated history as a background or setting, New Historicism treats history as a discourse: a network of power, ideology, and representation. In this view, literature and historical documents are analyzed not as separate domains but as parallel texts that reflect and influence each other.

Core Concepts of New Historicism Theory

Textuality of History and Historicity of Texts

One of the central tenets of New Historicism theory is that historical texts are not objective accounts. They are written, rhetorical constructs, subject to the same scrutiny as fiction or poetry. Similarly, literary works are not autonomous; they are immersed in their own historical moment, constituted by the discourses, tensions, and contradictions of their time. For instance, examining political pamphlets alongside a novel from the same period can reveal how both respond to and reinforce particular power structures.

Power, Discourse, and Ideology

Drawing from Michel Foucault, New Historicism emphasizes how power circulates through discourse through the way institutions, texts, and language produce knowledge and influence behavior. Literature is one such site where power is both exercised and contested. This means that a poem or story is not simply expressive or imaginative. It is an artifact of ideology, sometimes complicit, sometimes subversive. What matters is the interplay between the work and the systems of authority it inhabits.

Thick Description

Borrowed from cultural anthropology, the method of thick description provides critics the means to analyze both what a text says and how its meaning arises through cultural context. This involves close readings of literature alongside seemingly unrelated materials such as diaries, travel narratives, trial records, or sermons. Through this juxtaposition, New Historicism criticism uncovers the intricate dialogues between texts and the discourses of their age.

Methodology: How New Historicist Criticism Works

New Historicism avoids grand historical narratives and instead focuses on specific moments or documents that reveal tensions between authority and resistance, between dominant ideology and its anomalies. It privileges microhistory over sweeping theory, exploring how minor artifacts or obscure texts can shed light on larger cultural currents.

This method often involves:

- Juxtaposing a literary work with a non-literary text from the same period

- Reading both as culturally produced artifacts

- Investigating how both reflect struggles for power, voice, or legitimacy

- Highlighting contradictions within the dominant ideology

New Historicism Examples from Literature

In The Book of the City of Ladies (1405) by Christine de Pizan, New Historicist analysis could pair the text with ecclesiastical sermons or legal statutes governing women’s behavior in late medieval Europe. The literary work becomes an early feminist rebuttal, not only resisting the dominant misogynistic discourse but also embedded in the very language and structures it seeks to reform.

When reading Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko (1688), a New Historicist might examine travel logs, slave trade records, and colonial propaganda from Restoration England. Behn’s novella participates in the racialized and imperial discourses of her time while also exposing their brutality and contradictions, particularly through the protagonist’s tragic dignity.

Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist (2007) can be approached through the lens of post-9/11 policy documents, economic globalization reports, and interviews with immigrants. The novel narrates one man’s psychological unraveling while simultaneously questioning how power flows across borders, economies, and cultural perceptions, especially between the United States and Pakistan.

New Historicism vs. Traditional Historicism

While both approaches recognize the relevance of historical context, traditional historicism often treats literature as a passive reflection of its time. New Historicism, by contrast, sees literature as an active participant in the production of meaning. It rejects linear causality and seeks instead to reveal the networks of influence, suppression, and contradiction that govern the text’s emergence.

Moreover, traditional historicism tends to assume a fixed, stable past that can be uncovered and interpreted, whereas New Historicism insists that the past is always mediated by the present. Our reading of any historical moment is governed by the concerns and frameworks of our own time.

Critiques of New Historicism

Despite its contributions, New Historicism has faced several criticisms:

- Overemphasis on context: Some argue it dilutes the aesthetic and formal qualities of literature by subordinating them to context.

- Relativism: The view that all texts, including historical accounts, are constructed has led to accusations of historical relativism.

- Circularity: Critics claim that it sometimes reaffirms the very ideologies it claims to expose, by accepting power structures as inescapable.

Nonetheless, its tools remain indispensable for interpreting how texts circulate within the wider frameworks of power, ideology, and cultural production.

Why New Historicism Still Matters

New Historicism continues to influence contemporary literary studies because it offers a way to link literature with the forces that guide human lives, e.g., politics, religion, class, race, and institutional control. Its legacy lies not in a fixed method but in a sensibility: the insistence that texts matter because they speak within, and back to, the currents of their time. In classrooms, libraries, and scholarly work, the New Historicist method remains a vital mode of reading, a reminder that literature is always articulate about the world that birthed it.

Further Reading

New Historicism: A Brief Note by Nasrullah Mambrol, Literariness.org

Greenblatt’s new historicism by Dan Little, understandingsociety.blogspot.com