When Valeria Cossati purchases a black notebook on a Sunday morning—knowing full well that shops are closed and her act violates a minor civil regulation—something imperceptibly shifts. She lies to the tobacconist, hides the notebook under her coat, and later, at home, conceals it in a ragbag in their kitchen. The purchase is unremarkable, but the act is not. It begins the unraveling of an entire interior life.

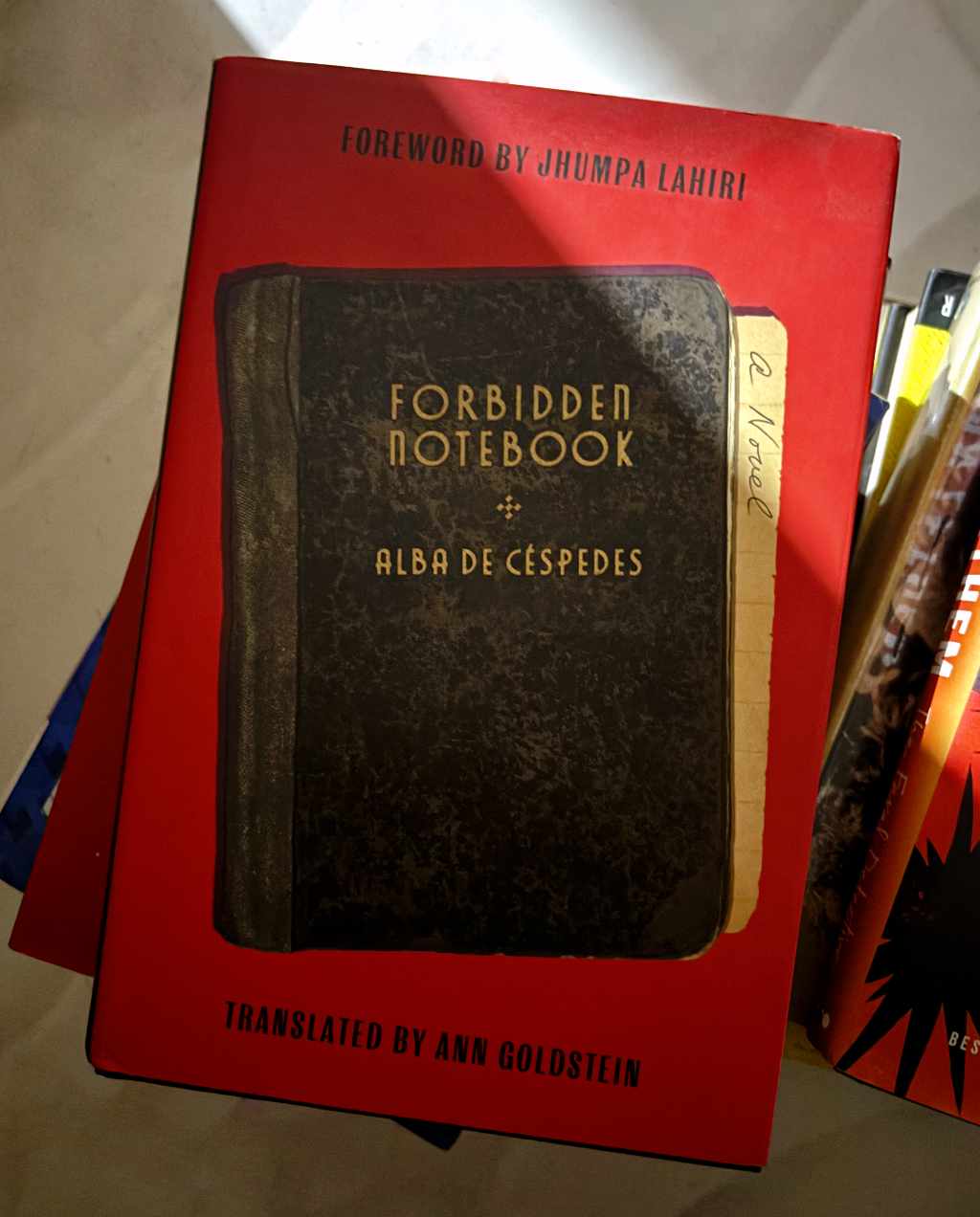

Thus begins the novel Forbidden Notebook (Quaderno Proibito, 1952), written by Alba de Céspedes and recently reissued in English translation. It opens with this nearly domestic deceit and avoids dramatic declarations or overtly political scenes. From the first line, the novel dismantles the supposed boundary between the personal and the political. What de Céspedes crafts through Valeria is a record of a woman becoming self-aware at the cost of her social legibility, separate from being a diary or confession in the conventional sense.

The notebook should not exist. And for that very reason, its presence speaks louder than anything written inside it.

Alba de Céspedes and Her Place in Literature

At once central and obscured, de Céspedes occupies an uneasy position in literature. Born in Rome to a Cuban diplomat father and an Italian mother, she was no stranger to political tension or divided identities. She worked as a journalist, was briefly imprisoned for anti-fascist activities, and spent her adult life writing fiction that complicated the sentimental trappings often imposed on women’s stories. Yet, for decades, her work was relegated to footnotes in discussions of midcentury fiction.

It is only since the recent reissuing of Forbidden Notebook in the Anglophone market that de Céspedes is being reconsidered on firmer terms. Critics now view her as a writer whose political thought and formal ingenuity require their own central focus, rather than as a supplement to more canonical male authors of postwar Europe. Consequently, the notebook in her novel is a countertext to the surface life she lived, exceeding the role of a mere prop—that of a woman expected to keep her thoughts orderly, her affections modest, and her suspicions to herself.

Structure and Narrative Device

De Céspedes constructs Valeria’s diary as a slow excavation of self-alienation, instead of writing it in the vein of self-expression. The writing grows halting and ambivalent, while the prose never achieves final clarity. As Valeria reflects on her family, her marriage, and her desires, she begins to suspect the futility of her own revelations. She becomes aware of a life that is simultaneously estranged from the version of herself she has sustained for decades.

The Fiction of a Diary

The novel’s structure mimics the episodic entries of a diary, but it does not conform to a diary’s rhythm of reflection and progression. There is no clear arc, no tidy resolution. The entries grow repetitive, hesitant, even contradictory. This is intentional, however. Valeria’s chronicle is a record of descent: the steady erosion of illusion, a broken sense of identity, and the loss of her established self.

There is a recurring instability in the way events are presented. Entries trail off or double back, sentences are left unfinished, and the past is recalled through the distorting filter of ambivalence. What emerges is a form of narrative that does not advance but turns inward, folding back on itself in troubling spirals. This structural avoidance of teleology reinforces the novel’s core tension: awareness does not guarantee change. The diary becomes the architecture of doubt.

The moral seriousness of keeping secrets and the anxiety of being found out parallel the emotional burden of recognizing one’s own dissatisfaction. What develops in the novel is the record of someone discovering she has lived inarticulately for years and that language offers no remedy, not the arc of a woman reclaiming her voice.

Voice and Distance

Valeria’s writing is not confessional. It is evasive, ambivalent, even halting. Her prose avoids catharsis because the objective is not to state what she truly feels but instead to track the fraying of her ability to articulate anything with clarity at all. Writing becomes an act of alienation rather than one of freedom—Valeria sees herself more clearly and finds that she cannot bear what she sees.

This is where de Céspedes’s work differs from diaristic fiction that merely indulges introspection. The forbidden act of writing does not alleviate the tensions in Valeria’s life; on the contrary, it exposes them. The husband she fears, the children who disappoint her, the job she needs but is ashamed to discuss—these are conditions structured to endure, instead of being problems to be solved by narrative insight.

Central Themes

Much has been made of Forbidden Notebook as a prime example of the diary as confessional in midcentury European fiction. But what de Céspedes achieves is more subtle. Valeria’s diary does not purify her nor empower her; its presence intensifies the contradictions of her daily life. Each entry tightens rather than releases the tension. Because the diary does not function as a metaphor for freedom, it becomes a physical burden, a thing to hide, guard, and fear.

Privacy and Estrangement

Valeria writes to observe the strangeness of her life, not only to free herself. The forbidden act of writing exacerbates the very tensions it tries to name. Her job, her marriage, her children—none of these become sources of true worth. They remain burdens she carries without acknowledgment.

The act of keeping the notebook mirrors the mechanism of repression: anything unspeakable must be concealed, even from the writer. Valeria’s deepest fear is the sudden clarity of her own perception; the risk of being discovered is secondary. Her estrangement originates with the self she used to be, having little to do with her relationships with others.

Domesticity as a Mechanism of Control

Valeria is a mother, a wife, and an employee, but the novel makes it clear that none of these roles provides her with grounding—they demand her disappearance instead. The apartment she inhabits is never violent, never haunted by overt cruelty, but simply swallows her. The labor of preparing meals, managing schedules, and absorbing her family’s emotional crises occurs without recognition. Her presence in the household is foundational but invisible.

Valeria’s notebook, then, is a gesture toward visibility, though a secret one. It becomes the only space where she can admit to disliking her daughter’s opinions or dreading her husband’s attention. In one passage, she notes that her family members speak to her as if she were the furniture. This was spoken with the passive entitlement of people who have never had to consider the consciousness of others, and not out of hostility.

Obedience Without Violence

There are no scenes of domestic abuse in Forbidden Notebook because the repression at work here is subtler, more banal. It functions through assumed hierarchies between men and women, between adults and children, and between those who speak and those who are expected to listen.

Valeria’s husband is not a tyrant in the theatrical sense; he is simply uninterested in who she is—he assumes that Valeria’s purpose is to maintain order and to reflect the values he upholds. When she begins to express disagreement, or when her presence becomes unpredictable, his reaction is confusion, not outrage. He does not recognize her dissent because he never recognized her subjectivity in the first place.

The novel modestly indicts a system in which power requires no overt enforcement but thrives instead on indifference and routine.

Characterization as a Critique

Valeria is not likable in any conventional sense. She envies her daughter, hides from her husband, lies at work, and mistrusts herself. Valeria is neither villain nor victim—she is a woman whose life has narrowed beyond recognition and who now senses it too late. The reader is not asked to admire her but to witness her. The act of witnessing is itself the novel’s most radical gesture.

What de Céspedes achieves through Valeria is the construction of a fully inhabited consciousness that has no outlet. Valeria’s writing acts as a mirror; through this mirror, she begins to perceive her role in life as miscast. She is not writing in search of transformation. With each diary entry, she uncovers more of what she cannot change: the rote gestures of caretaking, the neglect she experiences but cannot challenge, and the personality she has had to invent to remain intact.

Secondary Characters as Foils

The characterization of Valeria gains its definition through contrast. Her daughter, Mirella, espouses modern ideals, speaks with defiance, and appears to live with clarity. But her progressivism is superficial—she neither hears nor sees her mother’s distress. Her husband, Michele, is emotionally inert but consistent; his expectations of Valeria have calcified into something beyond critique. Even her son Riccardo, tender at times, fails to comprehend that his mother exists beyond the structure that supports his comfort.

No one in the household is villainous, but none are willing to recognize Valeria as a person independent of her function. Their absence of malice is what makes the arrangement more chilling. Their lack of attention is not a momentary lapse but a permanent condition. This subtlety in characterization reflects a more insidious form of power: one that demands no affirmation, only habitual erasure.

Cultural and Political Context

Set in the years following Mussolini’s fall, Forbidden Notebook captures a society that appears on the surface to be progressing. There is talk of elections, rebuilding, and modernity. But the ideological underpinnings of the past remain intact.

Women, in particular, are expected to uphold a certain image of moral stability. They are told that the war has passed, that life must go on, and that tradition matters. Valeria’s attempts to question her role are not met with violent opposition but with a shrug. Her discomfort is treated as inconvenient, her doubts irrelevant.

De Céspedes juxtaposes the modernity of Rome’s public life—its cafés, its offices, its intellectual debates—with the private stagnation of the Cossati apartment. Valeria listens to her daughter speak like a modern woman but cannot make use of that vocabulary herself. Public life may be evolving, but private life remains governed by deeply ingrained patterns of deference and invisibility.

A Book Rediscovered

Originally published in 1952 and translated into English the following year, Forbidden Notebook was soon forgotten outside Italy. It lacked the stylistic experimentation of contemporaries like Natalia Ginzburg or Elsa Morante and did not conform to the sentimentalism expected of women’s fiction. It was unsparing and difficult to classify.

Now, with a renewed interest in midcentury women’s writing—particularly from Italy and France—de Céspedes is being reexamined. Once considered minor, Forbidden Notebook is now recognized as incisive and subtly subversive. Though often reclaimed under the broader umbrella of Italian feminist literature, it avoids easy classification.

But more than its label, what matters is the novel’s refusal to make its protagonist an emblem. In Valeria, de Céspedes gives us a character who does not seek liberation in the usual sense—she is a woman whose thoughts threaten the fragile peace of her surroundings. The enemy is embedded in the routines of affection, in the forms of marriage, motherhood, and work.

De Céspedes writes a feminism that is skeptical, internal, and haunted by its own contradictions. It is a literature of thought, not of certainty. What makes Forbidden Notebook endure is its rejection of formula. It speaks of gender but does not argue; it reveals power but does not explain it. De Céspedes writes against repression with simmering persistence, instead of seeking immediate freedom.

Selected Passage with Analysis

But maybe it’s hard to maintain friendships for a lifetime no matter what. In reality, at a certain moment, each of us changes, becomes different, some go forward, others remain fixed, and thus we move in opposite directions, so there’s no longer a meeting place, no longer anything in common.

Page 37, Forbidden Notebook by Alba de Céspedes

This passage surfaces during one of Valeria’s increasingly introspective diary entries, as she reflects on the growing distance between herself and Clara, an old friend she no longer recognizes. More than a passing thought on friendship, the reflection echoes Valeria’s central realization: that the life she has inhabited for decades is no longer tenable because she herself has shifted inwardly. Valeria is not merely describing the slow erosion of a friendship but articulating, perhaps for the first time, the fear that she no longer shares a “meeting place” with anyone in her life.

De Céspedes’s sentence construction mimics the slow, creeping nature of estrangement. The repeated clauses — “each of us changes, becomes different, some go forward, others remain fixed” — suggest a wearied resignation. The rhythm reflects a mind turning over an idea without resolving anything, much like the diary entries themselves: private and half-formed. The diction remains plain, but the emotional toll is unmistakable. The absence of dramatic punctuation or metaphor intensifies the sense of subtle irreversibility.

In the broader architecture of Forbidden Notebook, this passage underscores the cost of internal awakening. As Valeria begins to see herself more clearly, she also perceives the unbridgeable gap between what she has become and what others continue to expect of her. The commentary on friendship thus becomes a more general meditation on intimacy, language, and recognition. It suggests that change, however imperceptible, renders the familiar unfamiliar — and that even the most cherished connections can wither from misalignment of inner lives.

Further Reading

The power of Forbidden Notebook’s hidden diary entries by Clare Thorp, BBC

A Diary’s Unwanted Insights by Sarah Chihaya, The New Yorker

Resistance fighter, novelist – and Sartre’s favourite agony aunt: rediscovering Alba Céspedes by Lara Feigel, The Guardian

I Was Wrong to Buy This Notebook, Very Wrong: On Alba de Céspedes’s “Forbidden Notebook” by Joy Castro, Los Angeles Review of Books