Catachresis is a literary and rhetorical device that involves the strained or incorrect use of a word, often as an intentional violation of linguistic convention. Unlike a simple malapropism which stems from ignorance catachresis serves a deliberate stylistic or expressive purpose. Writers employ it to create vivid imagery, evoke emotional intensity, or expose the limitations of language.

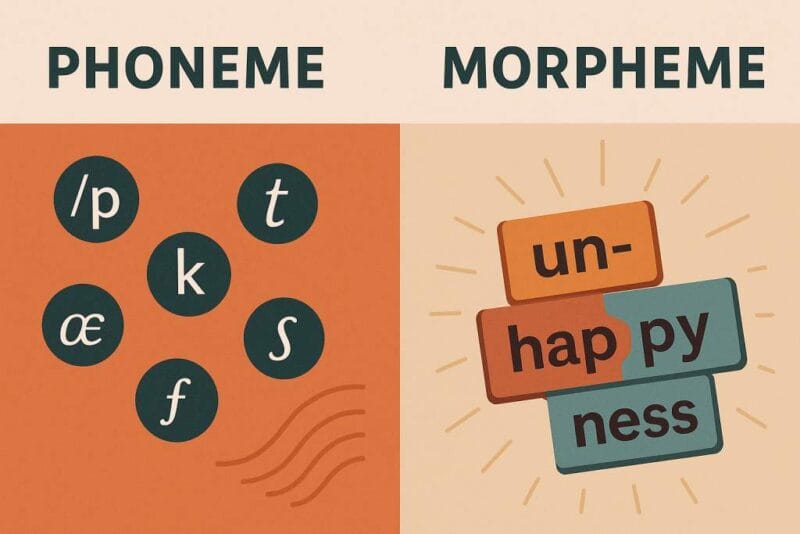

Derived from the Greek katachrēsis (“misuse”), catachresis occupies a unique space between metaphor and error. It stretches language beyond its ordinary boundaries, forcing words into unfamiliar contexts. This technique appears in poetry, prose, and philosophical writing, where precision and distortion coexist.

Defining Catachresis: Between Metaphor and Error

At its most basic, catachresis occurs when a word is applied in a way that defies conventional meaning. Examples include phrases like “the leg of the table” (inanimate objects do not have legs) or “to microwave an idea” (ideas cannot be cooked). These constructions lack a literal equivalent, yet they communicate meaning through imaginative association.

Unlike conventional metaphors, which rely on clear analogies, catachresis often involves a degree of semantic impossibility. Consider John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667) where, in Book II, he describes Death’s form through catachresis:

Here, the paradoxical phrasing (“shape it might be called that shape had none”) violates logical definitions, straining language to convey the incomprehensibility of Death’s form. This mirrors the epic’s broader use of catachresis to depict the indescribable (Hell, Chaos, divine beings).

Historical and Theoretical Foundations

Catachresis has roots in classical rhetoric, where it was classified as a form of abusio—a controlled misuse of terms. Ancient rhetoricians like Quintilian acknowledged its utility in expanding expressive possibilities. Later, structuralist and poststructuralist thinkers, including Jacques Derrida, explored catachresis as a demonstration of language’s inherent instability.

In Of Grammatology (1967), Derrida argues that all language relies on catachrestic structures, as words never fully capture their referents. This perspective frames catachresis not as an aberration but as a fundamental feature of linguistic expression.

Literary Applications of Catachresis

Intensifying Imagery

Writers use catachresis to amplify description when ordinary language proves insufficient. In William Shakespeare’s King Lear (1606), the titular character howls:

Cheeks do not literally crack, but the phrase conveys the storm’s ferocity and Lear’s unraveling sanity. The distortion heightens the emotional impact.

Exposing Linguistic Limits

Some authors deploy catachresis to highlight language’s inadequacies. Samuel Beckett’s The Unnamable (1953) features sentences like:

The contradiction underscores the impossibility of articulating existence while persisting in speech.

Satirical and Grotesque Effects

In Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal” (1729), the suggestion that the Irish should “eat their children” is a catachrestic hyperbole. The phrase shocks precisely because it violates ethical and semantic boundaries, critiquing British economic policies.

Distinguishing Catachresis from Related Devices

Catachresis vs. Metaphor

Metaphors establish coherent analogies (e.g., Time is a thief). Catachresis, by contrast, often lacks a logical counterpart (e.g., to elbow one’s way through a crowd—elbows do not function as verbs).

Catachresis vs. Malapropism

Malapropisms result from error (e.g., He’s a wolf in cheap clothing). Catachresis is intentional, bending language for effect.

Catachresis vs. Oxymoron

Oxymorons combine opposites (e.g., deafening silence). Catachresis forces words into unnatural roles (e.g., to hand someone a thought).

Modern and Experimental Uses

Contemporary writers continue to exploit catachresis for its disruptive potential. In Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (1973), the phrase “A screaming comes across the sky” assigns sound to an abstract trajectory, merging sensory and spatial disorientation.

For poetry, consider Sylvia Plath’s “The Applicant” (1965):

“A living doll, everywhere you look. / It can sew, it can cook, / It can talk, talk, talk.”

The reduction of a person to “it” violates grammatical and ethical norms, weaponizing catachresis to critique dehumanizing gender roles. The pronoun’s cold objectivity clashes with the intimate verbs (sew, cook, talk), creating dissonance that underscores Plath’s corrosive satire.

Conclusion: The Power of Linguistic Transgression

Catachresis reveals language as a malleable, often unstable medium. By violating expected usage, it generates new modes of expression, from heightened emotion to philosophical inquiry. Whether amplifying imagery, exposing linguistic constraints, or challenging a reader’s expectations, catachresis remains a vital tool for writers who test the limits of words. Its persistence across centuries confirms that language thrives not only on precision but also on calculated distortion, where meaning emerges not from correctness but from its daring misuse.

Further Reading

From ‘Hamlet’ to ‘The Tempest’, how Shakespeare used catachresis as a grammar tool by Shashi Tharoor, Khaleej Times