The writer’s fundamental struggle is the search for the perfect word. From the vast, disordered field of language, a single term must be isolated to carry a specific thought, image, or sensation. This act of ideal selection has a name: le mot juste. The phrase, a famous import from French, evokes a standard beyond simple correctness. It suggests a principle of selection so demanding it becomes a defining discipline of the craft, which governs the act of composition from the initial clause to the final period.

Defining Le Mot Juste

The direct translation of le mot juste is “the right word” or “the exact word.” This translation, however, fails to convey the term’s critical severity. Le mot juste represents not just correctness, but perfection—that single term whose meaning, connotation, and rhythm achieve an absolute, irreplaceable alignment with the writer’s intent. It is the word that, once found, makes all alternatives seem deficient.

This concept transcends mere vocabulary. It applies with equal necessity to the selection of a concrete noun, as does the cadence of a verb or the texture of an adjective. The search for le mot juste is therefore a search for linguistic inevitability. The writer works until the word on the page creates the impression that it could not be any other, that the thought has found its only possible verbal form.

Historical Context and Literary Significance

The principle of le mot juste is inextricably linked to the legacy of Gustave Flaubert. The 19th-century French novelist elevated the term from a stylistic preference to an obsessive literary doctrine. His famous declaration of spending days searching for “un mot unique” (a single unique word) encapsulates this ethos. For Flaubert, prose demanded the sculptor’s patience; each sentence required chiseling until it attained a rigid, polished form where every component was essential and unimpeachable.

This rigorous standard did not originate with Flaubert, but he became its most famous and demanding advocate. His influence established le mot juste as a cornerstone of modern literary aesthetics, championed later by writers like Guy de Maupassant and, in the English tradition, by proponents of precise prose such as Henry James. The concept thus signals a shift in artistic priority: from the grand sweep of plot to the minute authority of the sentence, from what is said to the exact manner of saying it. This places the writer’s effort not in the service of story alone, but in the pursuit of a specific verbal integrity.

Techniques to Find the Right Word

While finding le mot juste may seem like an intuitive process, it often requires conscious effort and purposeful practice. The following methods represent disciplined approaches to this central task of composition.

Exhaustive Enumeration and Subtraction

When a sentence feels approximate, the writer must generate a list of all plausible candidate words. This act of enumeration makes the available linguistic options visible. Each term is then examined for its precise denotation, its connotative aura, its syllabic composition, and its sonic compatibility with surrounding words. Candidates are subtracted until one remains—the word that survives this analytical elimination.

Synonym Scrutiny

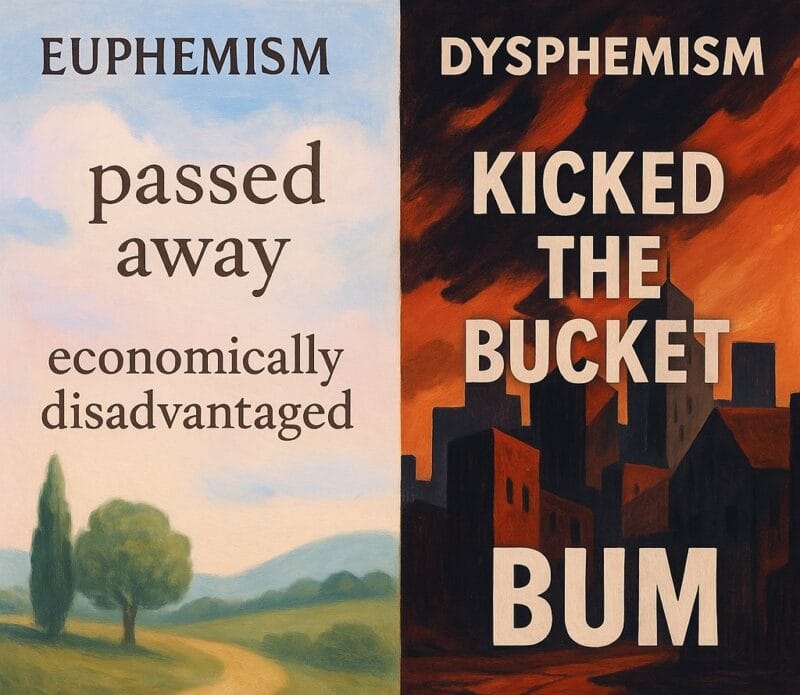

Thesauruses are essential, but their use must be critical. No two synonyms are perfect equivalents; each occupies a distinct niche of sense and association. The writer’s work is to diagnose the subtle divergence between “happy,” “joyful,” “elated,” and “content.” This scrutiny rejects the “merely different” in favor of the “exactly correct,” understanding that the right word often resides in the nuance that separates near-synonyms.

Contextual Audition

A word must be heard within the ecosystem of its sentence and paragraph. This requires reading drafts aloud. The ear detects friction that the eye misses—a rhythmic stumble, an awkward consonant clash, a tonal mismatch between word and context. The mot juste achieves acoustic and rhythmic integration; it sounds as if it belongs irrevocably to its specific verbal environment.

The Principle of Omission

A powerful technique involves asking what happens if a doubtful word is removed entirely. If the sentence’s core function remains intact and its clarity increases, the word was superfluous. The mot juste is never decorative; it is structural. Its omission would diminish the sentence’s capacity to convey the intended thought. This test separates essential language from filler.

Temporal Distancing

Judgment becomes clouded by proximity. After drafting, the writer must distance themselves from the text. Returning hours or days later provides a changed perspective. Words that seemed adequate may reveal their inadequacy; new, more exact possibilities may present themselves. This interval transforms the writer into a more critical reader of their own prose, a necessary condition for precise revision.

Le Mot Juste in Practice: Examples from Literature

The principle finds its proof in application. The following examples demonstrate how a single, exact word can concentrate a paragraph’s energy and define its effect.

Gustave Flaubert: Madame Bovary

Flaubert’s pursuit of le mot juste is well known. In Madame Bovary (1856), he describes Charles Bovary’s cap as “une de ces coiffures d’ordre composite” (one of those composite-order headdresses). The adjective “composite” does more than register displeasure; it is precise and damning. It suggests an ungainly assembly of disparate parts, a lack of unified style that mirrors Charles’s own muddled character. A simpler adjective such as “ugly” or “strange” would convey judgment but not this specific, analytical contempt. Here, “composite” operates with descriptive precision, the perfect word that offers analysis rather than mere insult.

Marcel Proust: Swann’s Way

Proust’s entire project is an exercise in meticulous verbal recovery. In the famous madeleine episode of Swann’s Way (1913), the narrator tastes the cake and feels a mysterious, powerful pleasure invade him. He writes: “Je tressaillis” (I shuddered / I started). The verb “tressaillir” is exact. It captures the physical, almost seismic disturbance of a buried memory being activated—not simply recalled, but violently reanimated. A weaker verb like “trembled” or “remembered” would fail to convey this sudden, visceral jolt of recognition.

Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita

Nabokov, who grew up trilingual in Russian, English, and French, wielded English prose with extraordinary, painstaking precision. Near the end of Lolita (1955), Humbert describes “the melody of children at play” and notes that “so limpid was the air that within this vapor of blended voices, majestic and minute, remote and magically near, frank and divinely enigmatic” individual bursts of laughter and play-sounds can be heard. The adjective “limpid,” applied to the air, is exact: it denotes a clear, transparent, almost pure medium, whose serenity cruelly contrasts with Humbert’s corrupt history and his acute awareness of the absence of Lolita’s voice from that innocent “concord.” Its faintly poetic association with water or glassy clarity resonates with the scene’s atmospheric stillness, turning a single word into a small, brilliant capsule of contradiction—Humbert’s aestheticized perception set against the moral falsity and irreparable loss the passage subtly exposes to the alert reader.

The Pursuit of Le Mot Juste

The pursuit of le mot juste is not a stylistic affectation; it is the writer’s core technical discipline. This principle demands a view of language as a medium of exactitude, where every chosen word represents a conscious, justifiable act of creation. It transforms writing from mere transcription into a process of relentless editorial judgment.

To engage with this principle is to accept a specific and demanding standard. It declares that clarity, economy, and expressive accuracy are not incidental virtues but necessary conditions for serious prose. While the perfect word may remain an elusive ideal, the rigorous search for it distinguishes casual composition from conscious literary craft. The writer’s labor becomes a continuous negotiation between the possible and the exact, a process where the quality of attention paid to individual words ultimately determines the authority of the finished work.

Further Reading

The Importance of the Right Word by Nancy Kress, Writer’s Digest

‘Bovary’ Translation Does ‘Le Mot Juste’ Justice by Maureen Corrigan, NPR

When did the phrase ‘le mot juste’ become a commonly used expression in English and other languages? on Quora

What’s your process for finding the right word to describe something? on Reddit