Irony imparts a distinctive flair to writing, often elevating narratives through unexpected developments. In Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex (c. 429 BC), the protagonist attempts to avert his fate, yet his every success ironically propels him closer to fulfilling it. Similarly, in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (1813), Elizabeth Bennet’s sharp judgments, though grounded in confidence and intelligence, ironically lead her astray. These cases illustrate how irony complicates and enriches stories, which opens up avenues for discovering hidden meanings and marveling at narrative intricacies.

This article explores the different types of irony and their uses, and through various examples explains their differences.

What is Irony?

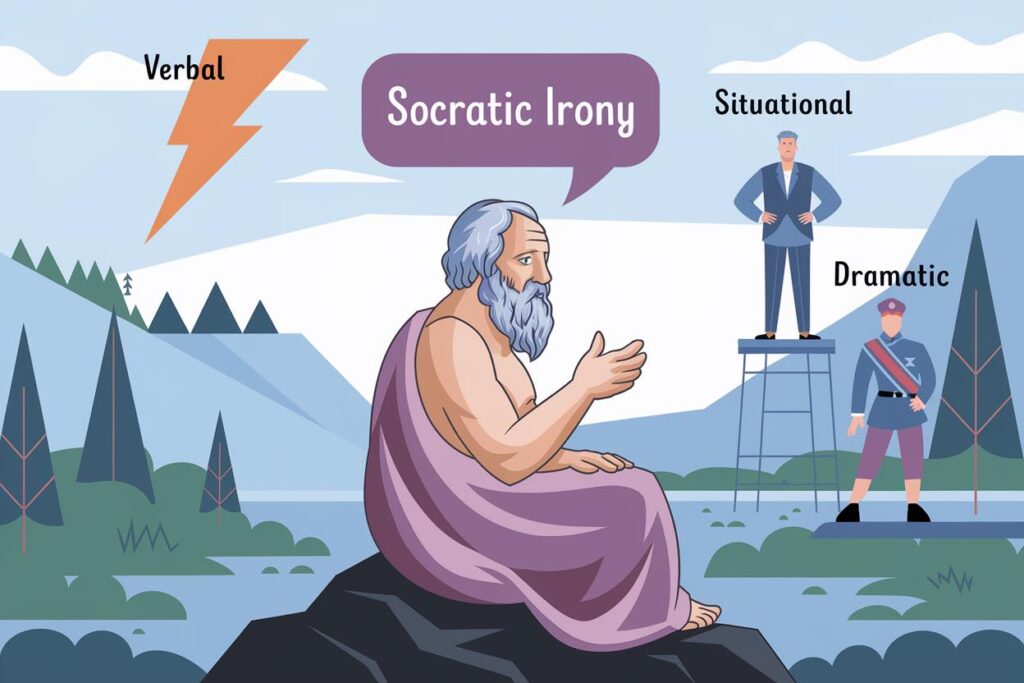

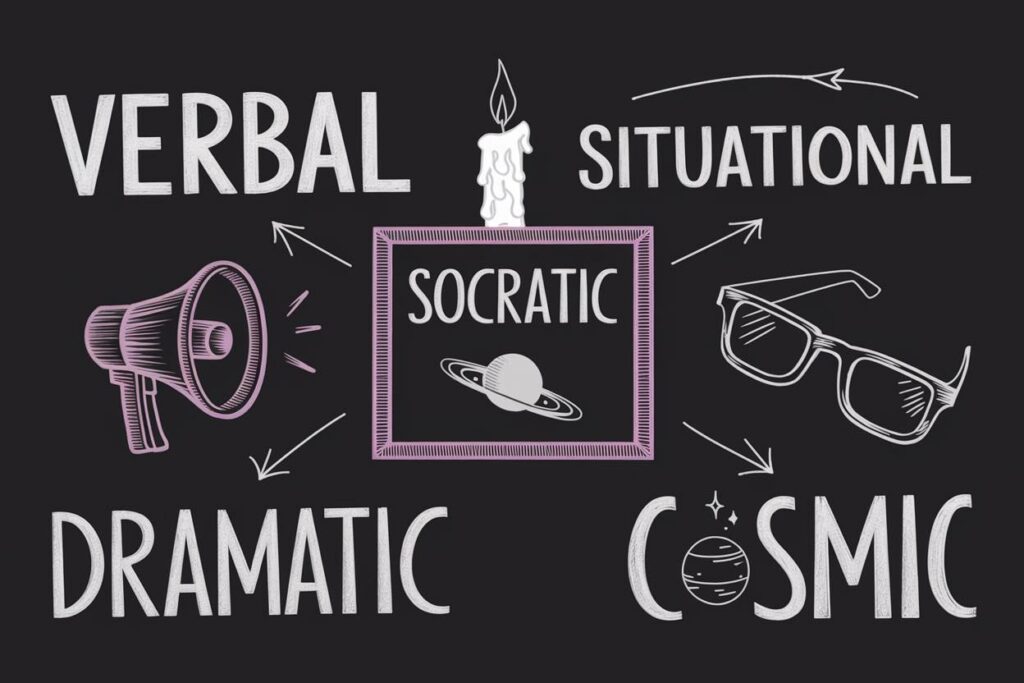

Irony is a subtle and complicated literary device that is one of the most important aspects of communication and storytelling. At the heart of irony is a result or statement that is the exact opposite of what one would assume or mean. This term broadly covers three main types: verbal, dramatic, and situational irony.

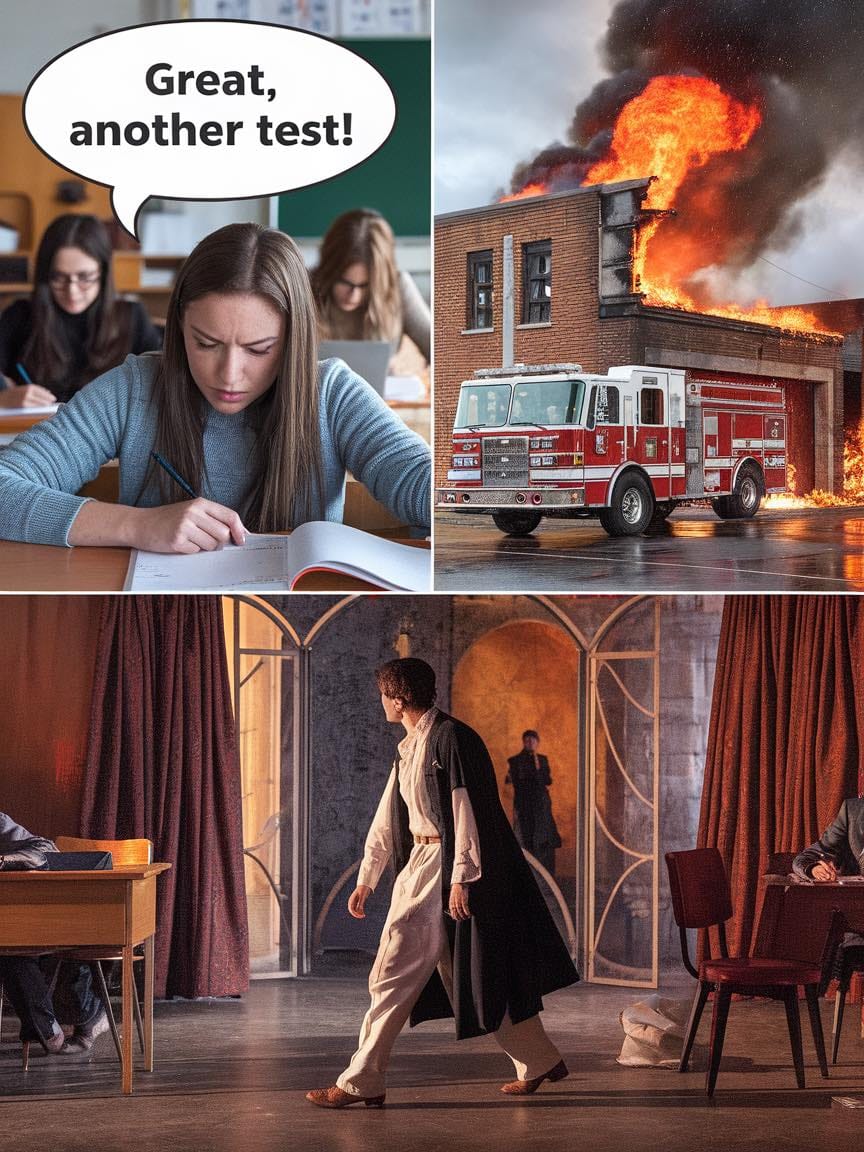

Verbal irony occurs when the literal meaning of a statement contradicts the speaker’s true intent, often delivering a sharp or humorous effect, as in saying “What a beautiful day” during a torrential storm. Dramatic irony, by contrast, engages the audience through a tension that arises when viewers or readers know critical information that characters remain oblivious to, amplifying the stakes and emotional impact of the narrative. Situational irony, perhaps the most striking, highlights the unpredictability of life by presenting outcomes starkly at odds with expectations, such as the ironic circumstance of a fire station succumbing to flames.

These forms of irony do more than entertain; they challenge assumptions and expose the contradictions and surprises that govern how people think and act. All three forms enrich our stories and discourse by revealing subtleties that go beyond what is immediately apparent. They provoke thoughtful reflection and uncover overlooked truths by adding depth and sophistication to narratives that engage both the emotions and the intellect.

Origin and History

The idea of irony has a long tradition deeply embedded in both linguistic and literary history. The very word itself comes from the Latin “ironia,” meaning “feigned ignorance.” This etymology highlights the insidious nature of irony, in which the speaker communicates a meaning contrary to the literal meaning.

Over centuries, irony has evolved as a powerful tool in literature, theater, and film, often used to manage reader or viewer expectations. It introduces three stages: installation, where the ironic situation is set up; exploitation, where it is fully developed; and resolution, where the irony is revealed or resolved.

In literature, irony can be classified further into five types: in addition to verbal, dramatic, and situational, there are cosmic and Socratic irony. Cosmic irony, or irony of fate, is the gap between human aspirations and the universe’s complete apathy. Socratic irony is the practice of feigning ignorance in order to draw out the other person’s ignorance, a technique that Socrates was known to employ.

In recent decades, “ironic” has become a popular term to describe a detached or subversive humor often seen in modern culture, like wearing a Christmas sweater for comedic effect. This turn toward optimism reveals a new face of irony, one that proves its flexibility and continued importance.

Types of Irony: An Overview

Irony, as a rhetorical and narrative device, creates unexpected contrasts that challenge assumptions and redefine meaning. It operates across various forms, each contributing uniquely to literature and discourse. The following sections outline its major types with illustrative examples.

Verbal Irony

Verbal irony arises when a speaker conveys a meaning opposite to the literal interpretation of their words. Unlike sarcasm, which is often sharp or disdainful, verbal irony can be nuanced and multifaceted, depending on tone and context. For example, a person looking at a completely empty fridge might say, “We have so many options for dinner,” contrasting the literal words with the reality of the situation. Writers use verbal irony to inject humor, critique, or reveal character motives. Its effectiveness lies in how it encourages interpretation and requires readers or listeners to uncover the speaker’s true intent.

What sets verbal irony apart from sarcasm is its broader range of tones and intentions. While sarcasm often aims to ridicule or express contempt, verbal irony can exist in a more neutral space, where the speaker highlights a contrast without any malice or mockery. For instance, verbal irony might serve to create humor, provoke thought, or underscore a thematic point, whereas sarcasm typically draws attention to flaws or shortcomings in a more cutting way. This flexibility allows verbal irony to play a central role in literature and communication, where it can be used to challenge assumptions or offer subtle commentary.

Situational Irony

Situational irony occurs when events defy logical expectations, resulting in surprising twists. This form of irony underscores the unpredictability of life and often carries a reflective undertone. A classic example is O. Henry’s “The Gift of the Magi” (1905). In this short story, a couple sacrifices their most valued possessions to buy gifts for each other, only to find their sacrifices render the gifts useless. The irony of the situation highlights themes of love and selflessness, which deepen the emotional resonance of the narrative. Situational irony thrives on its ability to invert expectations that compel audiences to reconsider assumptions about cause and consequence.

Dramatic Irony

Dramatic irony involves a disparity between what characters know and what the audience understands, which creates tension or intensity. This form of irony heightens engagement by positioning the audience as an omniscient observer. In Romeo and Juliet (1597) by William Shakespeare, the audience knows Juliet is alive while Romeo believes she is dead, leading to his tragic actions. The awareness of impending tragedy amplifies the narrative’s poignancy, which subtly emphasizes themes of miscommunication and fate. The power of dramatic irony lies in its ability to evoke anticipation and empathy, as audiences observe events unfold with heightened emotional involvement.

Cosmic Irony

Cosmic irony, also known as “irony of fate,” highlights the dissonance between human intentions and the indifference of larger forces, such as destiny or the universe. It raises questions about control and agency by showing how attempts to direct one’s future can result in unintended consequences. In John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men (1937), the characters dream of a better future, only to have their aspirations shattered by forces beyond their control. This form of irony reveals the tension between human ambition and life’s unpredictability, and it reflects the limits of human will.

Socratic Irony

Socratic irony employs feigned ignorance to expose contradictions or weaknesses in another’s argument. Named after the Greek philosopher Socrates, this method is a tool for intellectual inquiry and debate. By pretending not to know, the speaker encourages their interlocutor to articulate and scrutinize their beliefs, often revealing inconsistencies. In literature, Socratic irony is used to provoke thought and challenge assumptions. Its subtlety allows for the exploration of complex ideas, making it a powerful device in philosophical and rhetorical contexts.

Socratic irony can be considered one of the earliest and most classical forms of irony, as the concept of “ironia” (defined as “feigned ignorance”) is closely tied to Socrates’ philosophical method. The Greek term “eironeia” (from which the Latin “ironia” is derived) directly aligns with the strategy Socrates employed in his dialogues: pretending ignorance to stimulate discussion, challenge assumptions, and expose inconsistencies in others’ arguments.

While irony has evolved to encompass various forms (verbal, situational, dramatic, etc.), the Socratic method is a foundational example of how it was used intentionally in intellectual discourse. Socratic irony marks the beginning of irony in both philosophical and rhetorical contexts and laid the groundwork for its later use in literature, drama, and ordinary conversation.

More Irony Examples in Literature and Life

Irony in Literature

- In William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar (1599), Marc Antony repeatedly refers to Brutus as “an honorable man” during Caesar’s funeral speech, using verbal irony to undermine Brutus’s credibility and sway the crowd against him.

- In Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games (2008), the phrase “May the odds be ever in your favor” is repeated by those in power despite the grim reality of the contest. (verbal irony)

- In Erin Morgenstern’s The Night Circus (2011), the central rivalry ends with an outcome that contradicts expectations. The conclusion rejects the original premise of competition and stands as a clear example of situational irony.

- In F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925), Daisy Buchanan’s reckless driving causes Myrtle’s death. The moment is steeped in situational irony: Myrtle dies at the hands of the very people she idealizes, and the car she links to her escape becomes the instrument of her downfall.

- In Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (1960), readers recognize Tom Robinson’s innocence well before the jury announces its verdict. This gap between knowledge and outcome deepens the tragedy and exemplifies dramatic irony.

- In Roald Dahl’s “Lamb to the Slaughter” (1953), readers see the protagonist’s scheme unfold while the other characters remain clueless. (dramatic irony)

- In Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891), Tess strives to escape her troubled past and find happiness, only to be repeatedly thwarted by forces beyond her control, culminating in her tragic downfall. (cosmic irony)

- In Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851), Captain Ahab’s obsessive pursuit of the white whale leads to his destruction, as the very quest that defines his existence ensures his doom. (cosmic irony)

- In Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), Huck often pretends to misunderstand or agree with adults’ flawed beliefs, subtly highlighting their contradictions. For instance, he feigns ignorance about slavery to force others to expose the hypocrisy of their views. (Socratic irony)

- In William Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing (1599), Beatrice and Benedick disguise their feelings behind witty exchanges that rely on deliberate misdirection. Beatrice often pretends to feel indifferent toward Benedick, yet her words steer him toward admitting his affection. (Socratic irony)

Irony in Daily Life

- A person steps into a traffic jam and exclaims, “What a great day for a drive!” (verbal irony)

- A student walks into a chaotic classroom and remarks, “This looks like the perfect place to focus and study,” contrasting the words with the obvious disorder. (verbal irony)

- Purchasing a teacher a mug that reads “your the best teacher evah,” which clashes with a teacher’s calling to value correct spelling. (situational irony)

- An environmental activist is fined for littering after accidentally dropping a receipt. (situational irony)

- A person preparing a surprise party talks loudly about how quiet their evening plans will be, while the guests hiding nearby know the truth. (dramatic irony)

- A child hides under the covers during hide-and-seek, thinking they are invisible, while the seeker can clearly see the lump on the bed. (dramatic irony)

- A person dedicates their life to inventing a device to prevent natural disasters, only for their own invention to inadvertently cause one. (cosmic irony)

- A person diligently saves for retirement for years, only to unexpectedly win the lottery the day after deciding to stop working. (cosmic irony)

- A teacher might insist, “I’m not sure I understand,” forcing a student to articulate a point more carefully, thereby uncovering weak logic. (Socratic irony)

- A parent, noticing a child sneaking a cookie before dinner, might ask, “I thought that cookies were for after dinner—are the rules different now?” leading the child to reflect on their behavior without direct reprimand. (Socratic irony)

Further Reading

Isn’t It Ironic? Probably Not by Bob Harris, The New York Times

What Irony Is Not by Roger Kreuz, The MIT Press Reader

Oh, the Ironies: How Irony Got Its (Second) Meaning by Ben Yagoda, Literary Hub

In Defense of Irony by Joel Stein, Time