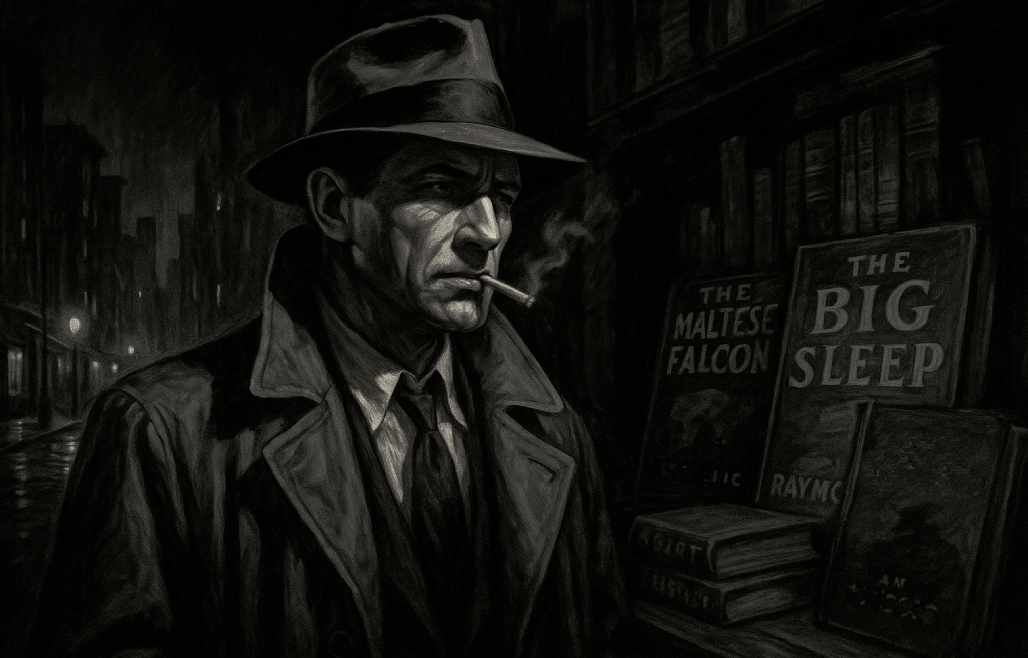

- The hardboiled detective archetype arose from American pulp magazines in the 1920s and 1930s, offering a grittier counterpart to the classic sleuths of Arthur Conan Doyle and Agatha Christie.

- Unlike Holmes or Poirot, who solved puzzles through logic and deduction, the hardboiled detective navigated corruption, violence, and crime-ridden streets, less concerned with restoring order than exposing its absence.

- Writers like Carroll John Daly, Dashiell Hammett, and Raymond Chandler established the model. Their detectives carried distinctive traits:

– Cynicism tempered by a personal code

– Violence as a tool of survival

– A sardonic first-person voice

– Alienation and independence - Philip Marlowe became the archetype’s most enduring figure, though others such as Sam Spade, Mike Hammer, Lew Archer, and the Continental Op each offered variations.

- Film noir, and later neo-noir, solidified the image, while authors like James Ellroy and Walter Mosley adapted it to new cultural contexts.

- Enduring through shifting eras, the hardboiled detective remains a symbol of survival in a society marked by corruption and compromise.

The figure of the detective has long been a staple in crime fiction, but not all detectives are cut from the same cloth. While the classic detective—think Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes or Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot—thrives on logic, deduction, and a clinical separation from the chaos of crime, the hardboiled detective emerges from a rougher, dirtier corner of literature. Born out of the pulp magazines of the 1920s and 1930s, this archetype stands as both a rebellion against and a reinvention of the hardboiled fiction.

This article explores the hardboiled detective archetype, its defining traits, its divergence from classic fictional detectives, and its enduring presence in literature and popular culture.

Hardboiled vs. Classic Detective Fiction

The contrast between hardboiled and classic detective fiction is sharp. The classic detective is often portrayed as a near-mythical problem-solver, equipped with near-infallible logic. Holmes, for instance, treats crime scenes as intellectual puzzles, with solutions that can be extracted through careful observation. Christie’s Poirot is meticulous and refined, his “little grey cells” positioned as the ultimate arbiter of truth.

The hardboiled detective, by contrast, works within corruption, vice, and violence. Instead of tidy drawing-room solutions, he navigates alleys thick with crime, where no clue is pristine and no motive pure. The hardboiled detective is less concerned with restoring order to society than with surviving it and exposing its lies. The stories are less about “who did it” than about what crime reveals about power, money, and human weakness.

The Birth of the Hardboiled Detective Archetype

The hardboiled detective archetype emerged during the Prohibition era, when American pulp magazines such as Black Mask sought a grittier style of crime story. Writers like Carroll John Daly, Dashiell Hammett, and Raymond Chandler stripped away the genteel settings of European detective fiction and replaced them with urban grit.

- Carroll John Daly’s Race Williams, appearing in The Snarl of the Beast (1927), is widely considered the first true hardboiled detective. Williams is violent, brash, and willing to shoot his way through a case.

- Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon (1930) refined the archetype, adding a sharper moral ambiguity and toughness grounded in Hammett’s own experiences as a Pinkerton detective.

- Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, beginning with The Big Sleep (1939), elevated the figure into something closer to literary art. Marlowe’s voice is sardonic and lyrical, his integrity paradoxically firm amid corruption.

This birth of the archetype was not merely stylistic but cultural. The detective became a man shaped by the city’s grime, a private investigator who could not rely on law enforcement because the police were often complicit in crime themselves.

Defining Characteristics of the Hardboiled Detective

- Cynicism and moral ambiguity: The hardboiled detective is distrustful of authority, skeptical of motives, and convinced that corruption is everywhere. Yet this cynicism does not collapse into nihilism. Figures like Marlowe still cling to a code that is personal, flawed, and non-negotiable.

- Violence as a language: Unlike the classic detective, who prefers deduction to force, the hardboiled investigator often communicates through fists or bullets. Violence is not glorified but acknowledged as the lingua franca of the underworld.

- First-person tough talk: The hardboiled detective archetype is inseparable from its voice. Chandler perfected the clipped, ironic first-person narration that both reveals and conceals. The voice is part shield, part performance, part survival tactic.

- Alienation and individualism: The hardboiled detective works alone, mistrustful of institutions. He inhabits the margins, both inside and outside the world of crime. This marginality positions him as both a critic of society and a casualty of it.

Key Figures of the Hardboiled Detective Archetype

The archetype of the hardboiled detective is best understood through its central figures. Some characters have come to embody the style so completely that they define its literary stature, while others expand its possibilities by offering alternative shades of toughness, cynicism, or psychological depth.

A few figures came to define its essence, while others offered distinctive variations. The following sections consider both the figure most often identified with the archetype and the wider cast of detectives who carried its influence into different directions.

Philip Marlowe: The Quintessential Hardboiled Detective

If Sam Spade set the mold, Philip Marlowe polished it into legend. In The Big Sleep, Chandler gives us a private eye who is both knightly and jaded, witty yet profoundly weary. Marlowe rejects easy rewards, choosing instead to hold onto a semblance of integrity.

Marlowe’s significance lies in his dual nature. He embodies the cynicism and toughness of the archetype, yet he also exudes a romantic streak. He is drawn to beauty but knows it deceives; he upholds principles in a world designed to crush them. His Los Angeles is a labyrinth of vice, and he walks through it with a mix of disgust and fascination.

Later works such as Farewell, My Lovely (1940) and The Long Goodbye (1953) deepened Marlowe’s introspection. In The Long Goodbye, Marlowe’s sense of loyalty is tested against betrayal, making him as much a tragic figure as a crime-solver.

Other Famous Hardboiled Detectives in Fiction

- Sam Spade (Dashiell Hammett, The Maltese Falcon, 1930): Sam Spade is cold, calculating, and less idealized than Marlowe. He is pragmatic to the point of ruthlessness, turning in his lover Brigid O’Shaughnessy for murder, even while admitting his feelings for her.

- Mike Hammer (Mickey Spillane, I, the Jury, 1947): Mike Hammer represents the extreme of the archetype: brutal, vengeful, and often politically reactionary. Spillane’s detective is less philosophical than Marlowe, more interested in retribution than reflection.

- Lew Archer (Ross Macdonald, The Moving Target, 1949): Lew Archer softened the archetype with psychological nuance. His investigations often expose family dysfunction, greed, and generational corruption. Archer remains tough, but his voice carries more compassion than Spade or Hammer.

- Continental Op (Dashiell Hammett, short stories, 1920s): Hammett’s unnamed “Op” was among the first true hardboiled detectives. As a Pinkerton agent, he represents the archetype’s professional roots: blunt, efficient, and loyal only to the job.

Hardboiled Detective Archetype in Popular Culture

The archetype quickly moved from pulp magazines into film and television. Film noir of the 1940s and 1950s crystallized the detective’s image: trench coat, fedora, cigarette smoke curling in dimly lit rooms. Humphrey Bogart’s portrayals of Spade (The Maltese Falcon, 1941) and Marlowe (The Big Sleep, 1946) defined the visual shorthand.

Later, the archetype evolved into neo-noir and modern reinterpretations. Writers like James Ellroy (L.A. Confidential, 1990) and Walter Mosley (Devil in a Blue Dress, 1990) updated the figure, situating the hardboiled detective in racially charged, historically complex contexts. Mosley’s Easy Rawlins, for instance, adds dimensions of African American identity and social history to the archetype.

On television, series such as True Detective (2014) echo hardboiled traits, pairing detectives who battle corruption both within themselves and within their environments. The archetype persists because its core concerns of crime, corruption, and isolation remain timeless.

Hardboiled Detective Archetype and American Culture

The hardboiled detective archetype emerged from conditions particular to the United States in the early twentieth century. Rapid urbanization, the rise of organized crime during Prohibition, and the sense that law enforcement was compromised created fertile ground for a figure who could move through corruption without being consumed by it. Where the European detective projected rational order, the American counterpart embodied a kind of moral endurance amid chaos.

This archetype also absorbed the anxieties of modern capitalism. Cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Chicago became stages for stories where wealth and power were closely tied to criminality. The detective, moving between glamorous mansions and seedy hotels, exposed the fissures of a society built on inequity. His work was less about solving puzzles than about revealing the structures of corruption that lay beneath prosperity.

Another layer is gender. The archetype was almost exclusively written as male, emphasizing toughness, independence, and emotional restraint as defining virtues. This construction reflected a broader cultural investment in rugged masculinity during a period when economic upheaval and shifting social roles unsettled older identities. Later authors would challenge this mold, but the original hardboiled detective remained closely tied to a vision of American manhood.

Why the Hardboiled Detective Endures

The hardboiled detective endures because he embodies contradictions that continue to fascinate readers. He is cynical enough to survive in a corrupt world yet committed to principles that prevent him from becoming indistinguishable from the criminals he pursues. His blend of toughness, wit, and flawed integrity makes him a figure who feels authentic even when the cases verge on the sensational.

This figure also endures because of his voice. The clipped, sardonic narration perfected by Chandler and Hammett turned the detective into both participant and commentator, a man who records the corruption he encounters while refusing to be sentimental about it. This voice has proven endlessly adaptable, shaping not only mid-century noir but also later genres from neo-noir novels to prestige television.

Finally, the archetype persists because the conditions that created him have never vanished. Corruption, inequality, and institutional distrust remain constants in modern life. Each time a writer crafts a private eye who prowls the city streets, narrating his suspicions with irony and grit, he reactivates a tradition that continues to mirror the darker undercurrents of society.

Further Reading

Hardboiled Detective on Wikipedia

Hardboiled vs Classic Detective Fiction by Lauren Shade, Novel Suspects

The 5 Best Hardboiled Detective Novels by Brett & Kate McKay, Art of Manliness

The Hardboiled Detective by cwhawes.com