In fiction, a character’s consciousness can enter the prose with such subtlety that the transition passes unnoticed. There are no quotation marks, no speech tags, no announcement of transition. One moment belongs to the narrator, the next to the character; yet, the syntax remains the same. We suddenly realize: this isn’t quite the narrator speaking anymore—it’s the character, almost, but not entirely. The technique responsible for this seamless movement is called free indirect discourse. Though subtle in form, it alters how fiction could articulate thought, perception, and contradiction from within the narrative.

Defining Free Indirect Discourse

Free indirect discourse is a method of narration in which the third-person voice momentarily aligns with the thoughts or speech of a character without using quotation marks or explicit attribution. It borrows the intimacy of first-person interiority but retains the structure and distance of third-person grammar. In doing so, it creates a blend—one that lets the diction, tone, and rhythm of a character’s internal perspective filter into the narrator’s voice.

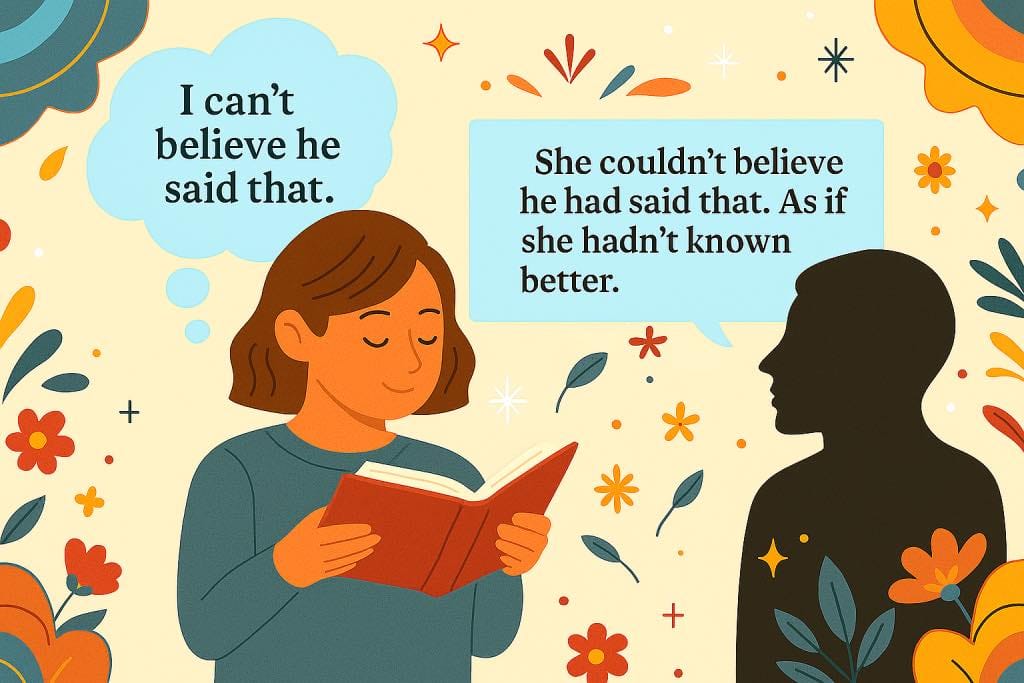

To see the distinction clearly, consider three versions of the same thought:

- Direct speech: “I can’t believe he said that,” she thought.

- Indirect speech: She thought that she couldn’t believe he had said that.

- Free indirect discourse: She couldn’t believe he had said that. As if she hadn’t known better.

That last sentence hovers. The narrator is present, but the judgment (cynicism) is the character’s. The line holds two voices at once: the narrative remains in third person, but the cadence and sarcasm suggest the character’s voice bleeding through. The narrator does not editorialize; the language has become shaded by someone else’s mood.

This tonal ventriloquism is not simply a trick of grammar; it opens the text to contradiction. The prose can now contain both the observing voice and the observed consciousness, operating together yet not always in agreement.

Features and Mechanics

There are several features that distinguish free indirect discourse from ordinary narration. The pronouns remain third-person. The tense typically matches that of the surrounding narration—often past tense. What shifts is the attitude embedded in the sentence: vocabulary suited to the character’s education or age, emotional judgments that would not belong to a detached narrator, or sudden idiomatic turns that disrupt the formality of the narration.

Writers use this technique not to relay information but to inhabit perception without surrendering authorial control. The narrator remains the one telling the story, yet steps aside just long enough for a character’s private thoughts to surface. The best uses of this narrative technique are those in which the rhythm of the prose bends almost imperceptibly, wherein a single phrase reveals the character’s bias, fear, or vanity.

Where It Operates in Narrative Point of View

Free indirect discourse functions entirely within third-person narration, but it is not confined to the omniscient mode. In fact, it appears most naturally in third-person limited, where the narrator’s access is restricted to the perceptions and thoughts of a single character at a time. This alignment creates the perfect conditions for the technique to emerge, since the narrative voice can adopt the character’s tone and diction while remaining anchored within that perspective, without any explicit shift or formal signal.

In contrast, third-person omniscient narrators may use free indirect discourse when focusing on one character, but the shifts must be managed carefully to avoid disorientation. When employed within a tightly limited viewpoint, the technique offers both flexibility and precision. It bends the sentence toward subjectivity while retaining the narrative distance of third-person form.

How to Recognize It

This technique depends on a tension between two voices: the third-person narrator and the internal perspective of a character. What makes it “free” is that it blends those voices without clear attribution or quotation. What makes it “indirect” is that it reframes the character’s thoughts or speech without quoting them directly. For this to work, the baseline needs to be a third-person perspective; otherwise, there’s no contrast for the character’s voice to filter through.

Free indirect discourse can be elusive because it disguises itself as regular third-person narration. But look closely, and you’ll find:

- Third-person pronouns and past tense are maintained.

- Tone and diction shift subtly to match the character’s internal register.

- Exclamations, rhetorical questions, or sarcasm often signal the intrusion of the character’s voice.

It’s a method that lets the narrator recede without disappearing while still giving us a glimpse inside the mind of the character, framed through their emotional lens.

Historical Development and Early Examples

Jane Austen

Although precursors can be found in earlier prose, the method gained prominence in 19th-century fiction, particularly in the work of Jane Austen. In Emma (1815), Austen regularly uses free indirect discourse to inflect her narration with Emma’s self-regard and misguided assumptions.

The hair was curled, and the maid sent away, and Emma sat down to think and be miserable. It was a wretched business, indeed!

The first sentence appears neutral, but the second one, particularly the final phrase, reflects Emma’s tendency to dramatize her discomfort. The phrase “a wretched business, indeed!” echoes Emma’s voice, not Austen’s. Austen does not announce the shift, nor does she distance herself from Emma’s feeling. Instead, she lets Emma’s language assume control of the sentence without an overt signal.

This technique enabled Austen to hold her characters gently to account. Rather than judging Emma through overt commentary, she lets the character reveal herself through her own internal exaggerations. The prose becomes shaded by irony, not by moral correction.

Virginia Woolf

Writers of the twentieth century continued to use it to more fluid effect, particularly as fiction began to explore perception not as a sequence of clear thoughts, but as an ongoing and sometimes disjointed interior drift.

Virginia Woolf made this technique central to the structure of her fiction. In Mrs. Dalloway (1925), Clarissa Dalloway’s thoughts surface mid-sentence, indistinguishable from the external narration, except in their inward turn of phrase. Woolf moves from one mind to another without pause, drawing no clear boundary between inner and outer language:

She felt very young; at the same time unspeakably aged. She sliced like a knife through everything; at the same time was outside, looking on.

The disorientation here is the point. Woolf shows us how Clarissa sees and feels herself without stepping outside the third person. This doubling—the sensation of being both in the world and outside it—reflects Clarissa’s divided perception. Rather than offering an explanation, Woolf embeds this tension in the rhythm and movement of the prose.

James Joyce

James Joyce used free indirect discourse with precision and subtlety, especially in the final story of Dubliners (1914), “The Dead.” Unlike Woolf’s fluid transitions or Austen’s irony-laced interiority, Joyce’s style is more restrained, yet no less deliberate in how it bends the narration toward the character’s private hesitations. Consider this passage near the end of the story, as Gabriel Conroy watches his wife at the hotel window:

A few light taps upon the pane made him turn to the window. It had begun to snow again. He watched sleepily the flakes, silver and dark, falling obliquely against the lamplight. […] His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.

The prose does not quote Gabriel directly, but the cadence of the final line—the repetition, the solemnity—mirrors his own ruminative mood. Though the narrator’s language remains intact, it becomes saturated with Gabriel’s emotion. This merging produces a tone that neither the narrator nor the character could generate alone. Joyce’s use of free indirect discourse is not flamboyant; it works in soft gradations, drawing the reader into a character’s interior drift without ever announcing the transition.

Other Writers

Writers such as Gustave Flaubert, Leo Tolstoy, and Henry James helped configure the technical range of free indirect discourse. Flaubert’s Madame Bovary (1857) is often cited as a landmark example, particularly in how Emma Bovary’s thoughts color the narration without a formal shift in point of view. Tolstoy, in Anna Karenina (1878), regularly employs the technique to explore his characters’ moral hesitations and self-justifications. James, who has a more elliptical style, also adopted this mode to present consciousness not as a fixed state but rather as a texture composed of impressions and revisions.

In contemporary fiction, the technique has continued to evolve. Rachel Cusk’s Outline (2014) demonstrates a modern refinement, where narration becomes almost porous, filtering dialogue and internal reflection so subtly that the boundary between the character’s reception of the world and the prose becomes difficult to distinguish. This evolution points toward a mode of narration that renders thought while also calling the stability of perspective into question.

What It Makes Possible

Free indirect discourse changes the relationship between author, narrator, and character. It lets one voice slip into another without interruption, shifting tone and perspective mid-sentence while preserving grammatical continuity. This makes it possible to suggest thought without declaring it and to reveal contradiction without commentary. The narrator remains present, but the sentence carries another cadence, drawn from private perception or internal tension.

Because of this, free indirect discourse avoids the limits of both first-person and omniscient narration. It does not bind the story to a single mind, nor does it pull away to survey from a distance. It moves instead between inner and outer speech, between seeing and feeling, often within a single line. That movement is where the form finds its power. And it remains one of the most flexible tools for representing how people experience themselves while being seen.

Further Reading

Free Indirect ‘Ducklings’ by Steve Coates, The New York Times

Free indirect style was so simple. He’d have to say something about it. How simple it was. Have to argue against Blakey’s view. by William Flesch, Stanford Humanities Center

How Jane Austen Changed Fiction Forever by Nerdwriter1, YouTube

How to read fiction that uses free-indirect discourse? on Reddit