An autological word is a word that describes itself. The term “autological” comes from the Greek autos (self) and logos (word or speech), making its etymology part of its function. For instance, “word” is, quite literally, a word; “English” is an English word; “pentasyllabic” carries five syllables in its own form. These words are not just quirky trivia; they belong to a specific category with implications in semantics, logic, and literary usage.

Autological words are contrasted with heterological words, which do not describe themselves. The distinction raises a well-known logical paradox when one asks whether the word “heterological” is heterological—an inquiry first formulated by the logician Kurt Grelling in the early 20th century.

Self-Descriptive Words and Their Literary Interest

Writers are naturally drawn to language that behaves in unusual or reflexive ways. Autological words create a meta-awareness of language as an object of attention, not just a transparent tool.

Examples of self-descriptive words include:

- Noun — functions as a noun

- Adjectival — serves as an adjective

- Unhyphenated — has no hyphen

- Word — a word

- Readable — can be read easily

Though these terms often go unnoticed in prose, their self-descriptive nature can be deployed for subtle irony, precision, or linguistic play, especially in metafiction or poetry that examines its own form.

Autology in Literature and Writing

The concept of autology can be exploited thematically. In literary writing, autological choices can lend a certain recursive quality, where the language and structure mirror or comment on themselves.

Writers such as Jorge Luis Borges and Italo Calvino have used autological elements to construct fiction that reflects on its own construction. In Borges’s The Library of Babel (1941), for instance, the story’s vocabulary and structure echo the infinite, recursive universe it describes. The word “labyrinthine,” frequently used in critical discussions of the text, is itself autological.

In poetry, the use of autological descriptors often goes unremarked but functions effectively. Consider Marianne Moore’s reference to “precise language” in poems that are themselves formally meticulous. The alignment between diction and metadiscursive content gives a poem a layered clarity without need for overt philosophical framing.

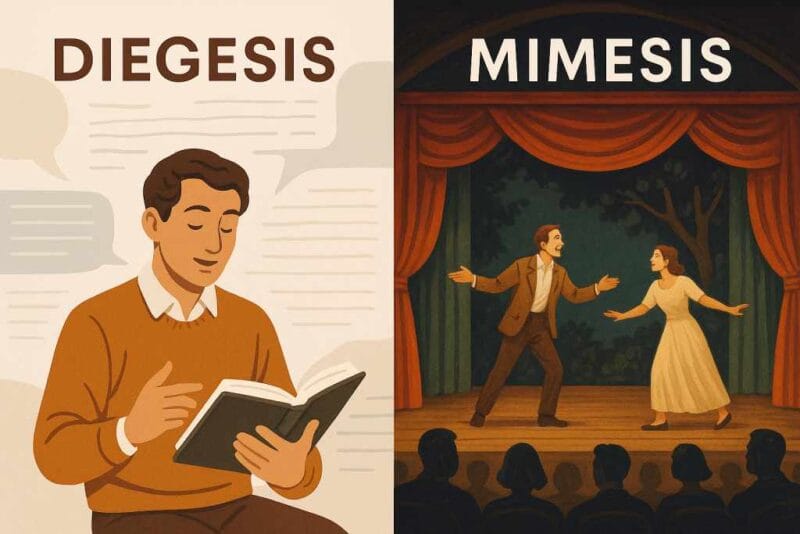

Heterological and the Grelling-Nelson Paradox

The concept of heterological (words that do not describe themselves) becomes essential when analyzing the limits of autological classification. This distinction was the focus of the Grelling-Nelson Paradox, a self-referential problem in semantics posed by Kurt Grelling and Leonard Nelson in 1908.

They proposed dividing adjectives into two categories:

- Autological: adjectives that describe themselves (e.g., “short” is short).

- Heterological: adjectives that do not describe themselves (e.g., “long” is not long).

The paradox emerges when we ask: Is “heterological” heterological?

- If “heterological” is heterological, then it does not describe itself. But that very fact would make it heterological, which forces it to fall under its own definition and creates a contradiction about whether it applies to itself.

- If “heterological” is not heterological, then it is not true that it fails to describe itself, so it must describe itself. That makes it autological, and therefore not heterological, which loops back again.

This produces a loop with no consistent resolution, similar to the structure of the Liar Paradox. The contradiction highlights how language, when turned inward without restriction, can generate insoluble problems. In literary contexts, these paradoxes aren’t just logical curiosities—they can be used to construct recursive structures, unreliable narration, or metafictional play.

Such paradoxes matter in literature not as pure logic problems, but as catalysts for narrative and structural experimentation. Writers interested in formal boundaries (David Foster Wallace, for example) have explored these tensions to question truth, coherence, and linguistic authority within fiction.

Semantic Paradox as Literary Device

Semantic paradoxes (of which autological/heterological distinctions are one) offer a way to construct texts that generate contradiction deliberately. Postmodern literature often employs these to disrupt interpretive stability.

For instance, in Samuel Beckett’s The Unnamable (1953), the narrator struggles with the impossibility of language adequately referring to itself or its source. The act of narrating is continually thwarted by the inadequacy of the terms available, a thematic echo of linguistic paradox.

Autological structures, when embedded subtly, may function as literary easter eggs. They reward close reading without becoming overtly clever or disruptive to the flow of language.

Metalanguage and Autological Construction

Metalanguage (language about language) is often the domain where autological words appear most naturally. Grammar guides, philosophical essays, and even poetry about poetry (ars poetica) offer terrain where self-descriptive words can serve a reflective function.

John Ashbery’s Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror (1974) critiques the attempt to represent the self through form and embodies its themes in language that behaves autologically. Words become what they describe. The poem mirrors the distortions of Parmigianino’s convex mirror through both imagery and syntax: reflections dissolve into digressions, and assertions unravel mid-thought.

When Ashbery writes, “The words are only speculation / (From the Latin speculum, mirror),” the etymology collapses the act of writing into its subject, revealing representation as a flawed, self-referential loop. The poem’s structure contains abrupt shifts and unresolved meditations that reproduce the fragmentation it theorizes while never naming it outright. Ashbery’s skill emerges in this slippage between form and content, where the poem, like the titular mirror, warps as it reflects.

Logical Vocabulary and Lexical Rigor

In essays on language and logic, precision matters. Terms like “definable,” “monosyllabic,” and “italicized” often describe themselves and are used intentionally to anchor arguments in clarity. Philosophers such as W.V.O. Quine and Ludwig Wittgenstein took such usage seriously, since their analyses turned on the slipperiness of language. Their work occasionally deploys autological words without drawing attention to them, preferring their function over their novelty.

In literature, this kind of lexical rigor appears in fiction that examines the logic of storytelling, such as Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire (1962). The fictional commentary on the poem draws attention to words that describe their own role, blurring fiction, commentary, and self-reference.

In a sense, autological words serve a dual function: they carry semantic content and demonstrate that content through their very form. While they may not appear frequently in direct discussion, their presence in literary writing can create subtle coherence between word and function. This reflexive trait appeals to writers interested in stylistic tightness, philosophical play, or structural recursion. In select cases, a single autological word can encapsulate an entire text’s ambition.

Further Reading

“Word” is a word is a word by Grammarphobia

When Words Describe Themselves, Or Sound Like They Do by Adam Cooper, Visual Thesaurus

16 Words that Describe Themselves by Arika Okrent, Mental Floss