Autobiographical novels function as alchemical transformations of a life. Authors of this genre employ the novelist’s essential tools of character, plot, and symbolic structure to distill personal history into a new substance. Their objective moves beyond documentary fact toward a more potent form of veracity, one rooted in psychological and emotional reality. Within a fictional framework, a rearranged event or a composite character can articulate interior truths that a strict chronology might fail to capture. This process is one of controlled interpretation, where the raw materials of memory and experience are refined into a coherent artistic whole.

This literary act of interpretation creates a charged duality within the text. Readers engage with an invented narrative while simultaneously perceiving the silhouette of the author’s life behind its contours. The genre’s distinctive power originates in this tension between fabrication and biographical source material. It positions the novel as a conscious act of self-construction, a space where an author, through fiction, can examine the past with clarity and invention. The works that follow each reveal the specific strategies behind this literary phenomenon.

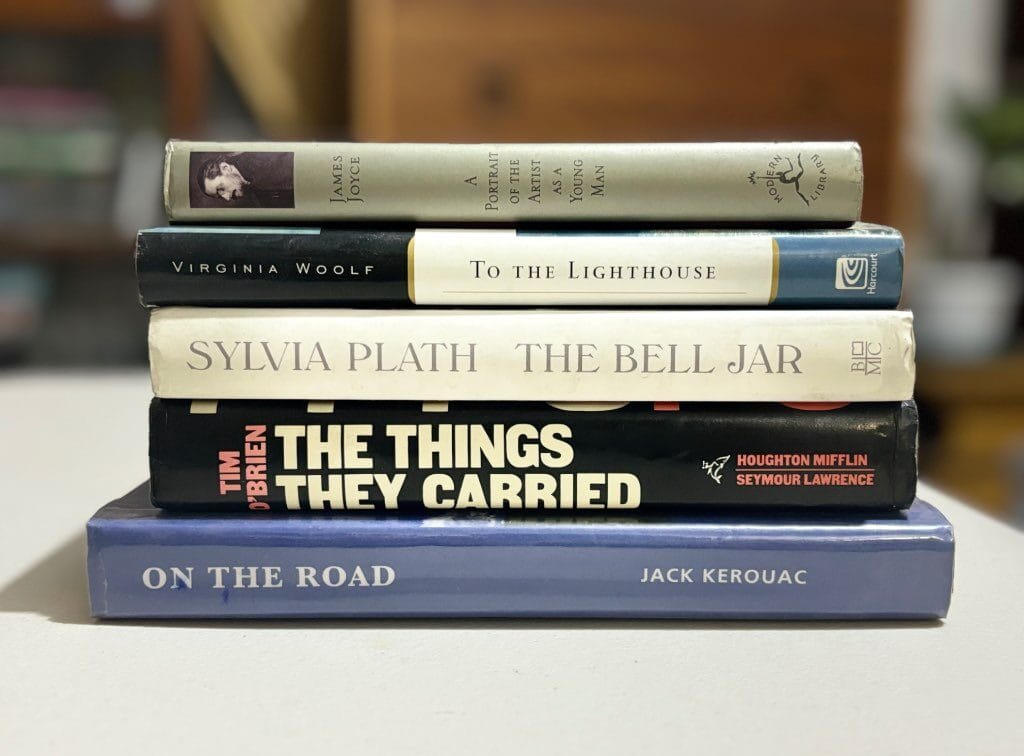

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by James Joyce

James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) traces the intellectual and emotional development of Stephen Dedalus, a young man in Dublin. His experiences with family conflict, Jesuit schooling, and Irish nationalism closely parallel Joyce’s early life, and he uses this parallel as a foundation for formal experimentation. The narrative adopts a style that evolves precisely with Stephen’s age and perceptual abilities, from infantile impressionism to sophisticated philosophical articulation.

This stylistic commitment frames the novel as a thesis on artistic formation. Its entire structure builds toward the famous final declaration: “I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.” Joyce frames this awakening as a logical outcome. Each crisis of faith and each conflict with national identity functions as an essential lesson. The narrative contends that the artist is manufactured by an environment through a process of opposition. Consequently, Joyce achieves more than a recounting of youth. He reconstructs the precise genesis of a consciousness according to its own developing logic.

To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse (1927) draws directly upon her childhood memories of holidays in Cornwall, translating this biographical material into the story of the Ramsay family and their seaside house. The narrative refuses a fixed perspective, instead dispersing a unified scene across the distinct perceptions of its characters. We encounter the world through a continuous shift between minds, from Mrs. Ramsay’s consolidations of social atmosphere to Mr. Ramsay’s rigorous philosophical anxieties. Woolf’s technique thus approximates the texture of memory itself, where solid events give way to layered, subjective impressions.

The novel’s famous tripartite structure formalizes this psychological realism. The first section, “The Window,” concentrates a world of domestic hope and tension into a single day. A short middle section, “Time Passes,” acts as a parenthesis: in a chillingly impersonal voice, it reports a decade of death, war, and neglect that befalls the empty house. The final section, “The Lighthouse,” documents a belated journey to the offshore tower, an attempt at reconciliation made after the family’s central emotional figure, Mrs. Ramsay, has died. Woolf’s autobiographical novel becomes an examination of how consciousness builds a temporary reality and how time and loss inevitably dismantle that construction. The book’s primary concern is the persistent, haunting process of remembering.

The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath

Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar (1963) details Esther Greenwood’s profound psychological crisis, a narrative that parallels Plath’s own experiences with depression and institutionalization during the summer of 1953. The novel’s power derives from its clinical precision in describing a disintegrating psyche. Esther’s first-person narration renders the world through a distorting lens; objects and interactions grow flat, distant, or grotesquely magnified beneath the jar of her illness. This narrative voice creates a stark authenticity, blurring any comfortable distinction between character and author.

Plath constructs her fiction as a forensic examination of a specific historical climate. Esther’s crisis is exacerbated by the limited options available to an intelligent young woman in the 1950s. The perceived choices, including conformist domesticity, degrading work, and patriarchal psychiatry, appear equally suffocating. The book documents a mind methodically rejecting all of these rigidly defined roles. Published under a pseudonym shortly before Plath’s suicide, the novel stands as a stark artifact of a consciousness confronting its own end. This proximity renders the fictional account a permanent component of the biographical tragedy.

The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien

Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried (1990) functions as a definitive example of autobiographical fiction. O’Brien, a Vietnam War veteran, presents a series of linked stories that blur the line between factual memoir and necessary invention. A narrator named “Tim O’Brien” recounts episodes from the war, often introducing them with claims about their accuracy. This narrative strategy forces a confrontation with the nature of wartime testimony. The question shifts from “Did this happen?” to “What does this story make you believe, and what does that belief require?”

The physical and emotional burdens catalogued in the title become metaphors for memory. O’Brien argues for “story truth” over “happening truth,” asserting that a fabricated detail can convey a wartime reality more accurately than a strictly factual report. A tale about a soldier’s sentimental longing for a lost love may be invented, yet it communicates the specific ache of isolation and fear more precisely than a combat log. The autobiography here resides in the collective emotional truth of the experience, reassembled through fiction to achieve a resonance that literal transcription could not provide. The book becomes a manifesto for fiction’s capacity to articulate truths that overwhelm factual language.

On the Road by Jack Kerouac

Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957) mythologizes the author’s cross-country travels during the late 1940s. The narrator, Sal Paradise, serves as Kerouac’s fictional stand-in, while the charismatic Dean Moriarty embodies Neal Cassady. The novel translates a specific period of restless motion into a generational anthem. Its spontaneous prose strives for the velocity and rhythm of jazz, attempting to capture the experience directly, without the filter of revision or conventional literary polish. This stylistic imperative mirrors the characters’ own flight from stasis and established order.

The book’s autobiographical essence resides in this fusion of style and subject. Kerouac presents an aesthetic performance as a way of being, moving beyond a mere record of events. The relentless movement, the pursuit of intense sensation, and the elevation of personal freedom above all social bonds are both the novel’s themes and the principles of its composition. On the Road crystallizes a moment of postwar American rebellion, transforming personal biography into the foundational text of the Beat Generation. The author’s life thus becomes indistinguishable from the literary movement it inspired.

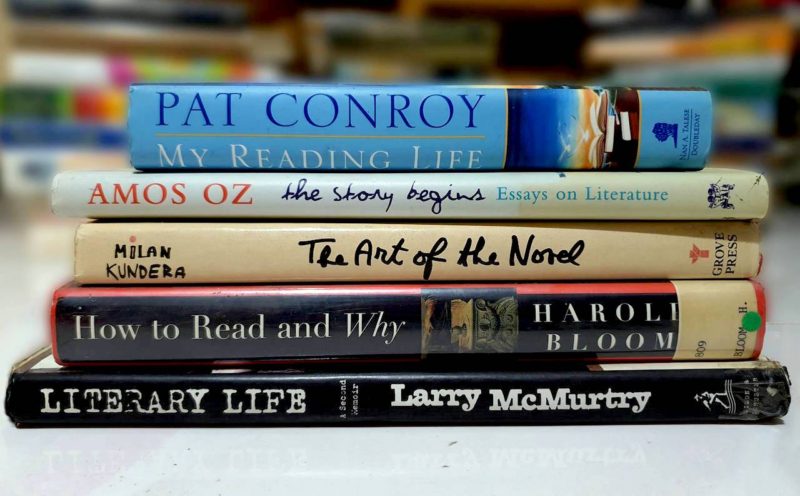

Further Reading

Some Thoughts About Autobiographical Novels by Judith Claire Mitchell, Jewish Book Council

Autofiction: What It Is and What It Isn’t by Brooke Warner, Publishers Weekly

Bad Genre: Annie Ernaux, Autofiction, and Finding a Voice by Lauren Elkin, The Paris Review

Novelistic autobiography, autobiographical novel? No matter by Edward Abbey, The New York Times