My Reading Note

Some sentences feel heavy while others feel light, and I started wondering what made them that way. So I began paying closer attention when I read, noting which passages stayed with me and which ones I forgot by the next day. After a while, I noticed the same qualities coming up again and again. This article is about one of those qualities: density.

Prose has a texture. Readers feel it in the density of sentences, in the pace of paragraphs, in the sound of words. In the guide Texture as Element of Prose Style: How Language Feels, the concept of texture is introduced along with six dimensions that contribute to it. This article takes a closer look at the first of those dimensions: density.

Of the qualities that surface again and again in memorable passages, density is among the most noticeable. Some sentences simply ask more of the reader. They layer implications into every phrase and demand closer attention. The examples cited in this article are drawn from novels that have held up under repeated reading, and the observations are what attentive reading reveals.

I used to skip dense passages thinking I would come back to them later. Most of the time I never did. But years later I went back to some of those books and found that the passages I once avoided were the ones worth reading.

What Density Is

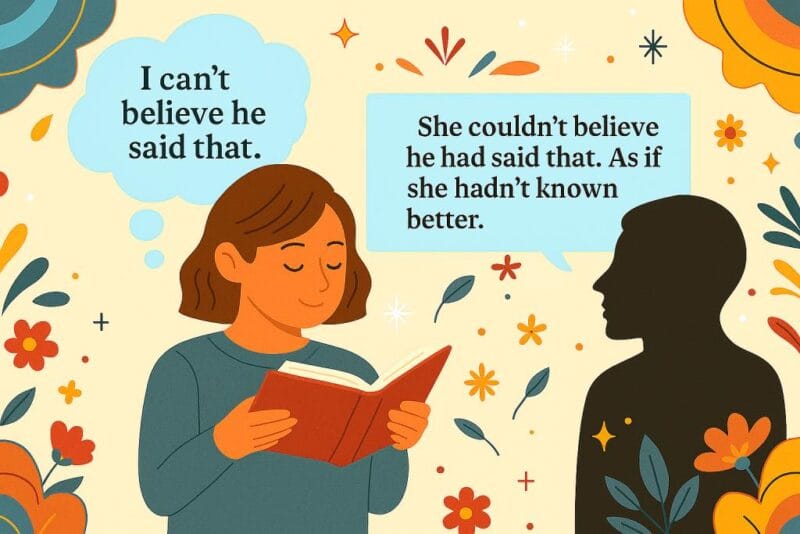

Density refers to how much content is packed into a given space. A dense passage loads meaning into every phrase through layered imagery, complex syntax, or compressed ideas. A sparse passage moves more directly and leaves room to breathe, using simpler constructions and letting each word carry one thing at a time.

Sentence length does not determine density. Both short and long sentences can be dense. Long sentences can also be sparse. The difference is not in how many words a sentence uses but in how much those words contain ideas that ask the reader to hold at the same time.

For a long time, I took dense prose as a sign that a book was not meant for me. Over years of reading, I came to see that some books simply ask more of their readers, and I need to read them differently.

Density in Short Sentences

Here is a passage from Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987):

She is a friend of my mind. She gather me, man. The pieces I am, she gather them and give them back to me in all the right order. It’s good, you know, when you got a woman who is a friend of your mind.

Every line here does more than one thing. “Friend of my mind” is not a phrase anyone speaks; it compresses an entire relationship into an unexpected construction. “She gather me” bends grammar to express something standard English cannot: a gathering that is not past tense, not present tense, but a continuous state. “The pieces I am” treats identity as something broken and collected. The passage is short, but each sentence asks the reader to hold multiple meanings at once.

A friend borrowed my copy of Beloved and returned it a week later, saying she couldn’t get past the first few pages. I asked what she meant, and she said the sentences felt too heavy. At the time I thought she just wasn’t trying hard enough. Now I think she was describing density without having a word for it.

Density in Long Sentences

Here is a passage from William Faulkner’s short story “That Evening Sun” (1931):

The streets are paved now, and the telephone and electric companies are cutting down more and more of the shade trees—the water oaks, the maples and locusts and elms—to make room for iron poles bearing clusters of bloated and ghostly and bloodless grapes, and we have a city laundry which makes the rounds on Monday morning, gathering the bundles of clothes into bright-colored, specially made motorcars: the soiled wearing of a whole week now flees apparitionlike behind alert and irritable electric horns, with a long diminishing noise of rubber and asphalt like tearing silk, and even the Negro women who still take in white people’s washing after the old custom, fetch and deliver it in automobiles.

Every part of this sentence does several jobs at once. The chain of “and”s keeps adding civic details—paved streets, utilities, laundry, automobiles—so the town’s modernization arrives as an almost overwhelming list rather than a single, stable fact. The description of the electric lights as “bloated and ghostly and bloodless grapes” turns infrastructure into an image of something overripe and unnatural, loading a mood of faint unease onto a technological change. Even the laundry run is doubled: it is literal (“bundles of clothes,” “motorcars”) and metaphorical (“flees apparitionlike,” “like tearing silk”), so movement, sound, and social transformation are compressed into the same phrases, making the sentence feel thick, continuous, and saturated with meaning.

I almost gave up on Faulkner the first time I read him. The sentences were so dense I could barely follow them, and I thought I just was not smart enough. It took years to realize the density was doing something I had not learned to read yet.

When a Long Sentence Is Not Dense

A long sentence can also be sparse. Here is Ernest Hemingway’s “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place” (1933):

It was very late and everyone had left the cafe except an old man who sat in the shadow the leaves of the tree made against the electric light.

The sentence accumulates detail after detail without compressing them. It moves linearly, with each phrase adding one clear image but not layering multiple meanings, so the reader follows along without holding simultaneous ideas.

Hemingway could write a long sentence that never felt heavy. I had to learn that length and density are not the same thing.

What Density Does

Density is not about difficulty. Some dense prose is immediately clear; some sparse prose is deeply ambiguous. The difference is in how many ideas the sentence asks the reader to hold at once. A dense passage demands more attention, more patience, and more willingness to let meanings accumulate. It rewards the reader who slows down.

The next article in this series will examine the second dimension of texture: omission—the power of what writers leave out. For the full framework, see the main article Texture as Element of Prose Style: How Language Feels.

I used to think dense prose meant long sentences. Morrison showed me otherwise. Faulkner showed me that long sentences could be dense too. Hemingway showed me they didn’t have to be.

Writing Styles: Key Elements, Types, and Examples

Texture as Element of Prose Style: How Language Feels

Light in August by William Faulkner

The guide to “Writing Styles” introduces the foundational vocabulary for discussing prose style. It covers terms like diction, syntax, and voice that appear throughout this article. The explainer on “Texture as Element of Prose Style” provides the larger framework into which this discussion of density fits and shows how density is one dimension among several. The review of Faulkner’s “Light in August” offers a concrete example of how density appears in a specific novel and demonstrates the ideas from this article in context.

Further Reading

The Secret to Getting Through Big, Dense, Difficult Books by Sebastian Castillo, The New York Times

For the Love of “Textual Density” by www.mikeduran.com

What is the densest most difficult novel worth reading? on Quora

Looking for dense, serious novels where the plot is not the point on Reddit