Explore This Topic

- Characterization in Literature: Types, Techniques, and Roles

- Character Arc: Transformative Journey in Fiction

- Character Development: Key Questions for Writers

- Character Analysis: Protagonists and Antagonists Explored

- Character Complexity in Literary Fiction

- Foil Character

- 10 Examples of Literary Archetypes

- Raskolnikov: A Character Analysis

Consider a story without a hero’s courage, a mentor’s wisdom, or a villain’s opposition: the narrative would lack a recognizable axis. Literary archetypes establish these essential narrative coordinates. These recurrent figures reside in our shared imagination, constituting the primary elements from which all complex characterization is built.

Understanding archetypes transforms character development from mere invention into deeper conversation with tradition. It turns character analysis from surface observation into an excavation of inherited form. To examine an archetype is to trace the lineage of a narrative idea, to see how old patterns are made new again through specific, defiant, or faithful execution.

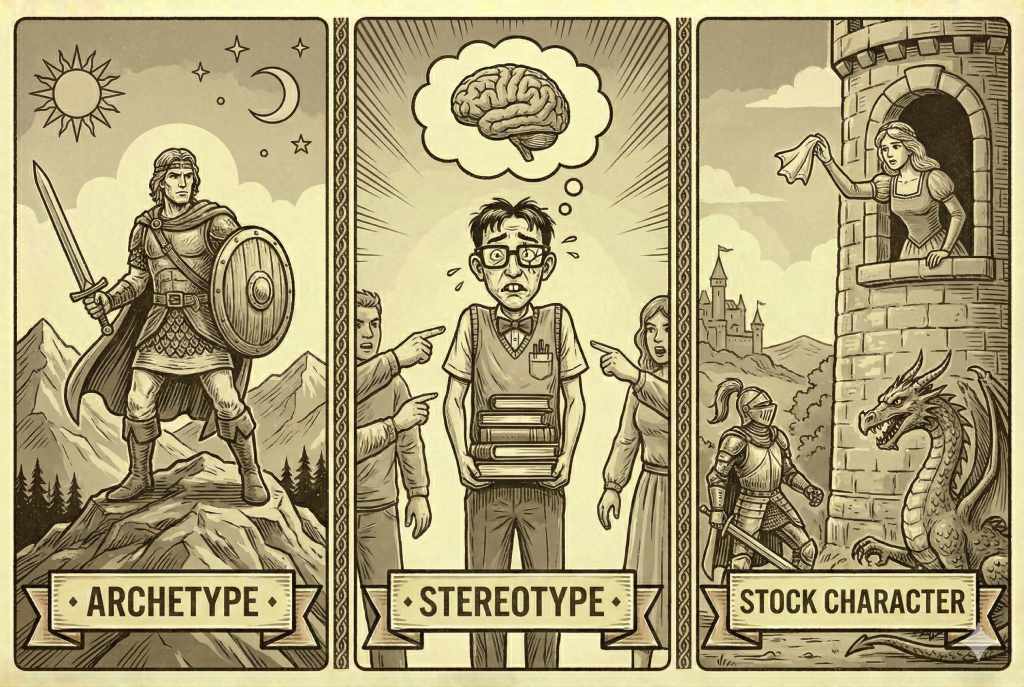

Archetype, Stereotype, Stock Character

A critical distinction separates the archetype from the stereotype and the stock character. Where the archetype operates as a generative function, the stereotype presents a fixed formula, and the stock character serves a static, utilitarian role. This distinction rests on narrative function, internal logic, and capacity for variation. Failure to recognize these differences leads to reductive interpretation and limits narrative possibility.

The Archetype: A Generative Function

An archetype is a narrative function: it operates as a specific, recurring role that performs essential work within a story’s logic, such as to challenge, to guide, or to corrupt. This function generates a field of narrative potential by establishing a set of conventional expectations: the “mentor” will provide wisdom; the “guardian” will offer protection. These expectations form a tacit contract with the audience. The writer’s creative act, therefore, lies in how this contract is executed: honored with classic fidelity, subverted for surprise, or deepened with new complexity.

The Stereotype: A Formulaic Prescription

A stereotype is an archetype drained of its generative power. It is a fixed, often reductive set of superficial attributes assigned to a character without internal logic or capacity for change. Where an archetype poses a question about human nature (What does it cost to protect?), a stereotype offers a prefabricated conclusion (The bodyguard is strong and silent). Stereotypes trade in cliché and assumption, systematically eliminating the potential for surprise or development. They operate as expedient labels, not as representations of consciousness.

The Stock Character: A Functional Unit

The stock character occupies a middle ground. It is a familiar, functional narrative unit, e.g., the “wise old bartender” the “corrupt official.” Its role is primarily utilitarian: to deliver exposition, provide a specific service to the plot, or establish a generic setting. A stock character may originate from an archetype but operates at a fixed, conventional level. It exhibits consistency instead of complexity. Its purpose is efficient communication, not profound exploration.

The 10 Archetypes

1. The Hero

The Hero functions as the narrative’s primary agent of change, confronting a central conflict to restore order or achieve justice. This role is defined by a capacity for consequential choice. The archetype’s potency emerges from the internal tension between duty and desire, a conflict that drives substantive character development. Frodo Baggins in The Lord of the Rings embodies this through the committed bearing of a destructive burden, his journey marking a profound character arc from innocence to tragic wisdom.

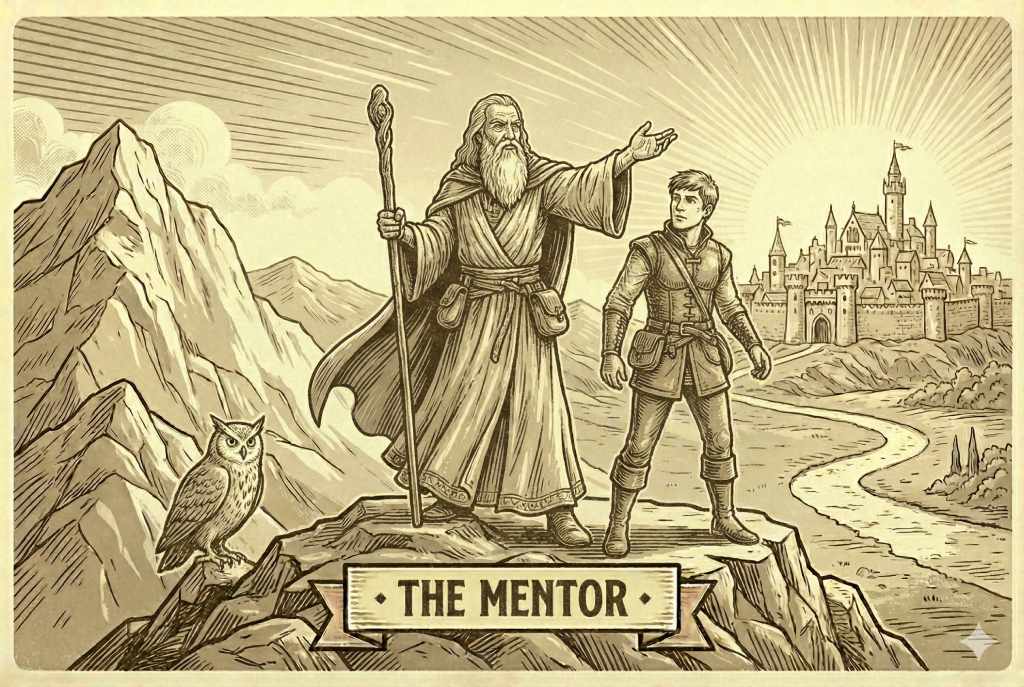

2. The Mentor

This archetype fulfills the narrative function of guidance, providing the protagonist with crucial knowledge, tools, or ethical counsel. An effective Mentor’s own history often serves as a foundational lesson. Their ultimate purpose is often catalytic, to equip The Hero for independent action. Gandalf’s strategic interventions and intentional absences in The Lord of the Rings force the Fellowship to cultivate their own resolve, illustrating how mentorship operates through enablement, not dependency.

3. The Sidekick

The Sidekick acts as the protagonist’s steadfast counterpart, serving functions of loyalty, contrast, and emotional grounding. This role reflects and humanizes The Hero, often embodying relatable fears that highlight the protagonist’s exceptional drive. Through unwavering support and dialogue, The Sidekick makes The Hero’s internal world legible. Dr. John Watson does not merely record Sherlock Holmes’s cases; his decency and perspective frame Holmes’s brilliance, making their partnership the narrative’s emotional core.

4. The Villain

The Villain embodies the principle of active opposition, functioning as the engine of the plot’s central conflict. Compelling iterations possess a coherent internal logic; their threat stems from a perverted virtue or a reasoned counter-ideology. By directly challenging The Hero’s goal, they force the decisive tests that propel the protagonist’s character trajectory. Their narrative power lies in their commitment to their cause, acting as a dark mirror to heroic conviction.

5. The Innocent

Representing purity and uncorrupted morality, The Innocent serves as a moral benchmark or a symbol of what must be protected. Their perspective of inherent trust exposes the complexity and cynicism of the surrounding world. Their narrative journey often involves a loss of this innocence, a transformation that marks the story’s emotional or ethical cost. Characters like Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist use this archetype to examine a specific society that would threaten such inherent goodness.

6. The Rebel

The Rebel functions as a narrative mechanism for instigating dissent. This archetype rejects established authority or a corrupt status quo. It externalizes the thematic conflict between control and autonomy. Their defiance possesses clear motivations and creates necessary instability. It forces other characters to choose sides and propels plot movement. Whether tragic or triumphant, as in Sophocles’s Antigone, The Rebel asserts individual will against systemic power.

7. The Ruler

This archetype embodies control and sovereignty. It establishes the story’s political and social structure. The central tension lies in the burden of power that pits the responsibility to protect against the temptation to corrupt. The Ruler’s decisions reveal their core motivations and flaws, which eventually determine political outcomes. The Ruler serves as a focal point for themes of leadership and justice, whether portrayed as a wise sovereign or a tyrant.

8. The Creator

Driven by the imperative to innovate or build, The Creator acts as a source of vision, often pushing against accepted limits. Their central conflict arises from the cost of creation: the obsession that damages relationships or the ethical boundary crossed for a breakthrough. They introduce change, wonder, or horror into the narrative’s world. Victor Frankenstein epitomizes this, where the act of creation becomes an uncontrollable entity exploring the peril of manifesting an idea.

9. The Lover

Defined by the pursuit of intimacy and connection, The Lover places relationships at the center of their motivations. This archetype explores the transformative power of love and desire and the vulnerabilities they expose. Their journey is one of emotional development, by seeking fulfillment in connection rather than conquest. Whether through the turbulent passion of Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights (1847) or the principled affection of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847), The Lover’s arc tests the strength of human bonds.

10. The Explorer

The Explorer archetype is motivated by insatiable curiosity. This figure drives the narrative into uncharted physical, intellectual, or spiritual territory. They are the vector for discovery, confronting the unknown. The core tension lies between the safety of the familiar and the peril of the undiscovered. This conflict fuels their character development. From Odysseus to modern cosmic voyagers, they embody the impulse to seek and to cross established frontiers.

Archetypes as Narrative Grammar

Archetypes constitute the foundational syntax of character. They are the recurring functions that establish a narrative’s dramatic potential. To employ or analyze these functions is to engage with the deep structure of a story. These patterns form the common language that renders character complexity both legible and significant. Mastery of this language, this grammar of characterization, is the necessary preliminary step for constructing a functional fictional character or for discerning the architecture of an existing one.