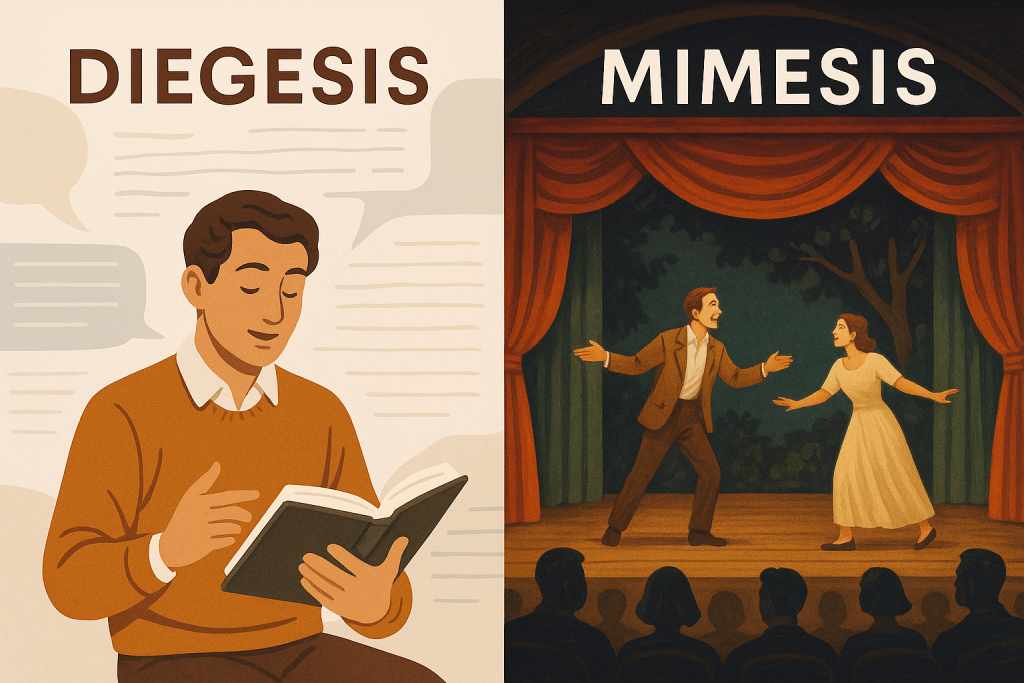

Literary storytelling moves through two distinct channels: telling and showing. These two methods, often presented in tension or in tandem, determine not only the structure of a story but also the experience it constructs. The classical terms for these narrative modes are “diegesis” and “mimesis”—a pair of ancient concepts that remain central to how fiction works.

Understanding the distinction between diegesis and mimesis is not a matter of theory alone. These modes form the underlying mechanics of how stories are communicated. A novel either speaks through a narrator who interprets, or simply presents action as though it unfolds before us without commentary, depending on how the work balances these two methods of representation.

Diegesis: Narrative Through Mediation

Diegesis refers to the act of telling. In literary terms, it is the mediated report of events through a narrator’s voice. The world of the story, such as its characters, incidents, and settings, is filtered through the consciousness of someone recounting them. This figure may be omniscient, limited, reliable, or unreliable, but always acts as an establishing presence. In the diegetic mode, readers are always aware of the narration as a construct, of events being formed by an authorial voice or a narrating character.

Plato introduced the term to distinguish between direct representation and narrated account. In The Republic (c. 375 BC), he criticized poets for imitating characters rather than speaking in their own voices, associating diegesis with philosophical clarity and mimesis with dangerous illusion. Aristotle, by contrast, did not assign such moral value, and in his Poetics (c. 335 BCE), he recognized both as legitimate forms of dramatic and poetic expression.

In fiction, diegetic narration can manifest in varying degrees of remove. Consider Rachel Cusk’s Outline (2014), where the narrator serves as unobtrusive conduit for other people’s stories. The book’s structure relies almost entirely on diegetic narration by presenting conversations as recollected monologues with little dramatized interaction. Here, the act of telling becomes the actual narrative.

Diegesis enables commentary, reflection, and selective emphasis. It can condense time, summarize years in a paragraph, or deliver philosophical musings that extend beyond the characters’ immediate awareness. It is a technique of control, often lending fiction its rhetorical texture.

Mimesis: Representing Without Apparent Mediation

Mimesis is the direct presentation of events. The term, drawn from the Greek word for imitation, refers to the dramatization of action in a way that minimizes narrative intrusion. When literature renders dialogue, gesture, conflict, or description as though they occur in real time, it engages in mimetic representation.

In mimetic passages, characters speak and act without the visible intercession of a narrator’s voice. This is the principle that governs drama, which is wholly mimetic by design. In fiction, however, the mimetic effect is always partial, since no novel can entirely escape narration. Still, the mimetic mode aspires to immediacy, to the illusion of witnessing.

Writers such as Ernest Hemingway have famously pursued this mode. In The Sun Also Rises (1926), dialogue and understated observation dominate, with little overt explanation or interpretation. Characters reveal themselves through what they say and do, rather than what the narrator tells us about them. In this way, mimesis builds meaning from within the scene, not from an external viewpoint.

The mimetic mode heightens realism, even when dealing with imaginary worlds. It creates space for subtext, tension, and ambiguity, requiring the audience to draw conclusions from the unfolding action rather than relying on narrative commentary.

The Difference Between Diegesis and Mimesis

The most crucial difference between diegesis and mimesis lies in narrative distance. Diegesis introduces a narrator who selects, interprets, and recounts; mimesis withdraws that presence to foreground the represented action.

This distinction, however, does not divide literary works into two clean camps. Most fiction blends both. A story may begin with a diegetic summary, narrow into a mimetic scene, and return to commentary. Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be? (2010) often moves between these registers, presenting stylized interviews, conversations, and memoir-like exposition. The transitions between diegesis and mimesis blur, directing the text to mimic thought while still dramatizing experience.

What changes between diegesis and mimesis is the position of the audience. With diegesis, the audience listens to a telling. With mimesis, they are positioned closer to the stage of events. The mode used determines how information is revealed and what degree of interpretive authority the reader is granted.

Narrative Composition

The interplay between diegesis and mimesis defines the rhythm, voice, and architecture of a story. Their use is not a binary choice but a compositional strategy. Writers modulate between telling and showing to control emphasis, pace, and psychological tone.

Exposition and Economy

Diegesis allows for compression. Events that are not central to the plot or emotional arc may be summarized or alluded to. A narrator can traverse decades in a few sentences or provide context that would feel artificial if dramatized. This function is vital for exposition, background, and shifts in time or place.

Teju Cole’s Open City (2011) offers a reflective, meandering form of diegesis. The narrator wanders through New York City recounting thoughts, memories, and past conversations. The structure is built on associative movement rather than dramatized conflict, and its power lies in accumulation rather than event.

Scene and Intensity

Mimesis, by contrast, serves as the focus of dramatic engagement. When writers want readers to feel the intensity of a moment, they slow the narrative and let the scene unfold. In mimetic passages, sensory detail, dialogue, gesture, and pacing take precedence. The effect is immersive because it recedes behind the action, not because the narration disappears entirely.

Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (2019) frequently shifts into scenes of mimetic clarity. A single conversation, gesture, or moment of violence is rendered in almost cinematic detail. Though the book is framed as a letter, its most memorable sections dramatize personal trauma through mimetic confrontation rather than abstracted commentary.

Shifts in Perspective and Mood

A subtle shift from diegesis to mimesis or vice versa can signal a change in mood or consciousness. Stream-of-consciousness narration often straddles both modes. In Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation (2014), short fragments alternate between factual, summarizing narration and vivid, momentary scenes that capture domestic fracture and interior unrest. The fragmentation itself becomes a structural marker of movement between telling and showing.

Writers also use diegesis to create irony or opposition. A narrator may describe an event with detachment, while the scene, rendered mimetically, suggests a different reality. This distance between narrator and scene, or between voice and event, is a crucial technique for establishing comprehension.

Beyond Fiction: Broader Applications

While the concepts of diegesis and mimesis originate in literary and dramatic theory, they extend beyond fiction into film, oral storytelling, and even digital media. In cinema, voice-over narration is a diegetic tool, while visual storytelling, especially without commentary, leans toward mimesis. In interactive narratives, such as video games, the player’s immersion depends largely on mimetic structure.

In nonfiction as well, memoirs and essays alternate between reflective diegesis and scene-based mimesis. Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts (2015) flows between analysis and memory, between philosophical discourse and lived anecdote, enacting an oscillation between modes that mirrors the subject’s shifting identity.

The tension between diegesis and mimesis is not only a technical matter. It touches the very heart of how narrative builds meaning. To tell is to interpret; to show is to evoke. A storyteller who understands how these modes function does not merely construct events, they sculpt attention, control time, and manage distance.

The richest works of literature rarely commit to one mode exclusively. Instead, they move between them, using each to intensify the other. Diegesis and mimesis, far from being opposing forces, work together to define the aesthetic, philosophical, and emotional architecture of a story.

Further Reading

Diegesis on Wikipedia

Mimesis on Wikipedia

Mimesis and Diegesis by Tim Ralphs, timralphs.com