The word “vellichor” carries a strange allure. Coined in the twenty-first century, the word has spread widely through online lists of unusual vocabulary, yet its legitimacy as a “true” word remains contested. To understand the word, one must look not only at its origin but also at how it engages with literature, language, and the cultural imagination surrounding books.

Defining Vellichor

Vellichor is most often defined as the wistful, nostalgic feeling that arises when browsing in a used bookstore. The word points to more than the presence of books on shelves, however. It gestures toward the history pressed into them: creased spines, marginal notes, and faded pages that suggest the hands of many earlier owners. The word attempts to distill into language an atmosphere familiar to anyone who has stepped into a secondhand shop filled with volumes that carry the trace of other lives.

Origin and Coinage

The earliest known use of vellichor can be traced to John Koenig’s The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows (2013, later expanded in 2021), a project dedicated to inventing words for otherwise nameless feelings. The book’s title itself signals the intention: to fill gaps in the lexicon by crafting new linguistic vessels for complex emotions. Vellichor stands out as one of the most widely circulated of these creations, making its way into blog posts, social media feeds, and even personal essays.

Etymologically, Koenig derived the term from the Latin vellere (“to pluck or tear”) and chorus (suggesting space or place). The construction is more imaginative than strictly etymological, but it lends the word a sense of antiquity that helps explain why it feels authentic even though it is a modern invention.

Is vellichor a real word?

Here lies the debate. Some language purists argue that because vellichor does not appear in standard dictionaries such as the Oxford English Dictionary or Merriam-Webster, it cannot be considered “real.” Others counter that any word in active use is real, regardless of whether it carries institutional approval.

Language evolves through adoption. Shakespeare’s coinages such as “blushing” or “fashionable” entered English because they were useful and memorable. While vellichor has not yet reached that level of widespread integration, it occupies a gray zone: not fully official, but far from imaginary. Its presence in essays, online communities, and even bookshop marketing demonstrates that it has gained traction as a meaningful lexical item.

Vellichor in Literature and Reading Culture

The Feeling in Classic Works

Although the word itself is new, the emotion it describes appears throughout literature. Writers have long captured the aura of old books and the spaces that house them. Walter Benjamin’s essay “Unpacking My Library” (1931) meditates on the aura of personal collections, where every secondhand book is marked by the trace of earlier readers.

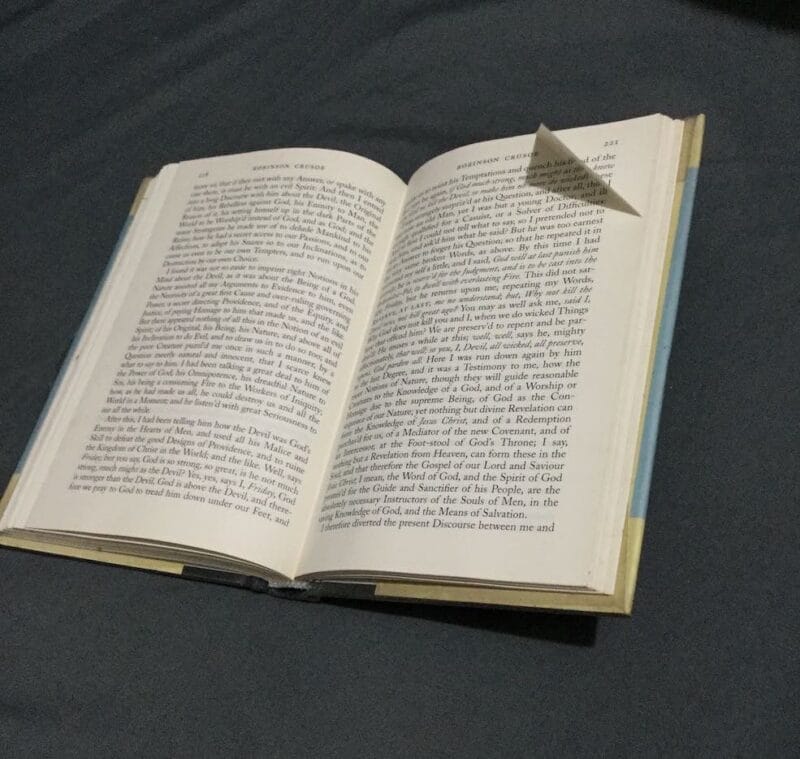

Even before the coinage of vellichor, writers described feelings that resemble it. Charles Lamb, in essays such as “Detached Thoughts on Books and Reading” (1822), reflects on the peculiar charm of secondhand volumes. He notes how marginalia, dog-ears, and inscriptions turn a book into a palimpsest of past owners, where every mark speaks of a vanished presence. His meditations capture the same wistful atmosphere that vellichor names, even if the word itself would not be invented for another two centuries.

The Bookshop as Symbol

The secondhand bookstore often functions in fiction as a site of memory and possibility. Jorge Luis Borges, in works like “The Library of Babel” (1941), constructed spaces where books accumulate into infinity, a metaphor for knowledge and loss. George Orwell in his essay “Bookshop Memories” (1936) writes with wry affection about the strange melancholy of working in a small bookshop. Both capture facets of vellichor—the wistfulness, the dusty shelves, the sense of standing within an archive of forgotten worlds.

Vellichor and Vocabulary: Why Words Like This Matter

Neologisms such as vellichor highlight how vocabulary stretches to accommodate emotions that feel universal yet unnamed. They demonstrate the creative elasticity of English and show that language is not only preserved in dictionaries but also continually renewed by writers and communities.

The coinage of vellichor also illustrates how internet culture accelerates the spread of words. A single invented term, once shared on blogs or social media platforms, can achieve a resonance that rivals older entries in the lexicon. In a way, the word functions as both a poetic invention and a case study in linguistic change.

Related Words and Concepts

- Neologism: Vellichor belongs to the wider family of neologisms or words recently coined or newly adopted. English has absorbed countless neologisms over centuries, from scientific terms to colloquialisms. Its status as a neologism does not diminish its validity; it simply places it on the threshold between invention and permanence.

- Nostalgia: The feeling described by vellichor is tied closely to nostalgia. Unlike nostalgia for childhood or home, however, this version is impersonal. It arises from objects once owned by strangers, which suggests a longing for stories never lived but somehow shared through the medium of books.

- Bibliophilia: Book lovers may recognize vellichor as part of bibliophilia, the affection for books as both physical objects and intellectual companions. For bibliophiles, the charm of used bookstores lies in their unpredictability: the chance of discovering a forgotten edition, inscribed with a name that sparks curiosity about its prior owner.

Vellichor in Popular Culture

Though absent from canonical dictionaries, vellichor has surfaced in cultural usage. Independent bookstores have adopted the word in marketing campaigns. This taps into its aura of wistfulness. Creative writers occasionally use it in poetry or fiction, which lends a sense of novelty and emotional precision. Online, it circulates in the same vein as words like “sonder” (another of Koenig’s inventions). As a result, it gains symbolic value in communities drawn to unusual vocabulary.

Whether it achieves lasting acceptance will depend on whether future writers and speakers continue to find it useful. Some neologisms fade after brief popularity, while others root themselves firmly into common speech.

Why Vellichor Persists

The persistence of vellichor may lie in its capacity to articulate a sensation that many recognize but had struggled to name. The moment of wandering through a used bookstore, feeling both comforted and unsettled by the presence of countless past readers, demands language that standard vocabulary could not quite supply. By condensing that sensation into a single term, vellichor satisfies both emotional and linguistic desires.

It may remain marginal, or it may, like many once-obscure words, gradually find a permanent place in English. Regardless of its fate in dictionaries, it continues to enrich conversations about literature, memory, and the language we use to capture fleeting moods.

Further Reading

Vellichor on The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows

Of Violets and Vellichor : an ode to my love for writing by Alisha Behera, Medium