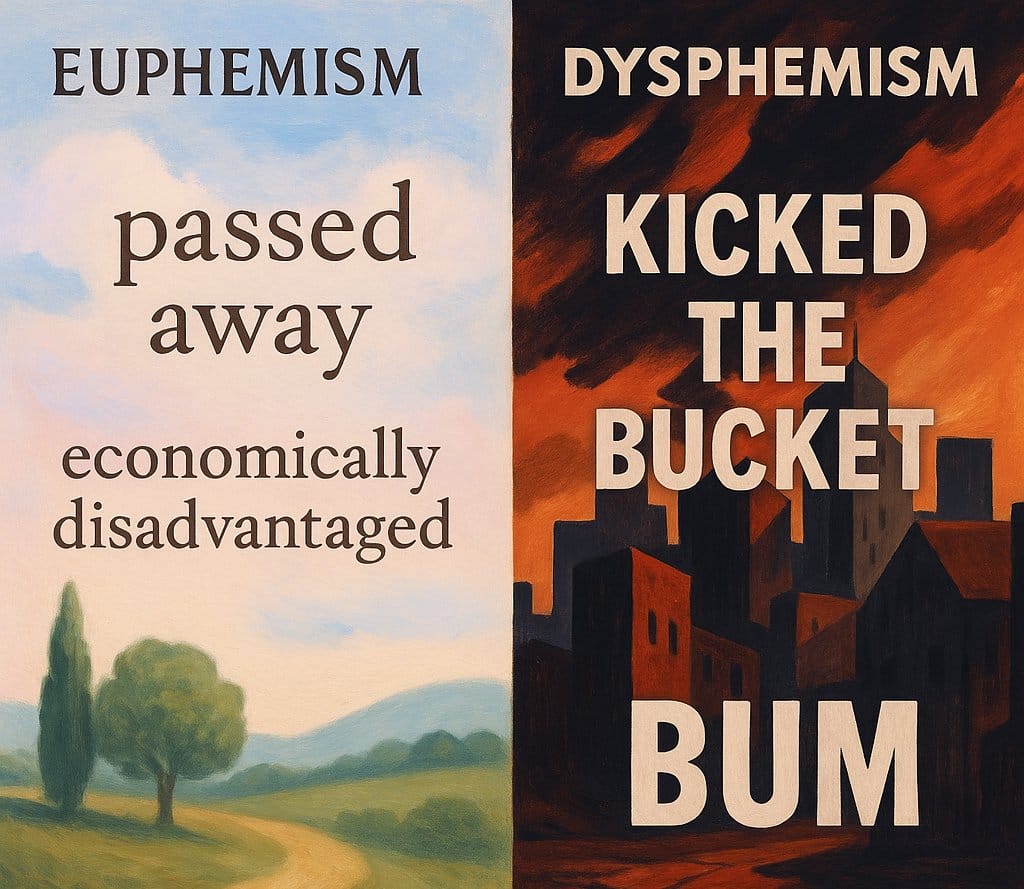

Writers and speakers have always molded language to soften or intensify what they say. Two rhetorical devices stand out in this work of molding tone: euphemism and dysphemism. Both concern the substitution of words, yet their purposes move in opposite directions. Euphemism smooths the harshness of expression, while dysphemism sharpens it to sting or provoke. Together, they show how words carry denotation and affect social and emotional response.

Euphemism and Dysphemism in Rhetoric

The rhetorical impact of both devices lies in how they guide emotional response. Euphemism often signals tact, diplomacy, or respect for cultural taboos. Dysphemism tends to frame opposition, criticism, or satire. When political debates replace tax relief with tax burden, or when critics refer to spin doctors instead of public relations officers, the choice of words shifts the emotional charge of the argument.

Euphemism Examples in Everyday Language

Euphemisms often cluster around subjects considered uncomfortable:

- Death and dying: “Resting in peace” instead of dead

- Bodily functions: “Powder room” instead of toilet

- Employment: “Downsizing” instead of firing

These substitutions show how language shields speakers and listeners from unpleasant realities while maintaining social harmony.

Dysphemism Examples in Common Speech

Dysphemisms, however, sharpen the blow:

- Food: “Junk food” instead of fast food

- People: “Bum” instead of poor individual

- Places: “Hellhole” instead of poor neighborhood

Euphemism and Dysphemism in Literature

In “Politics and the English Language” (1946), George Orwell criticized how vague, inflated, or euphemistic diction concealed brutality. His examples include pacification for the bombing of villages, elimination of unreliable elements for executions, and rectification of frontiers for forced population transfers.

Dysphemism, by contrast, chooses a harsher expression to intensify negativity. Where euphemism avoids offense, dysphemism heightens it. Shakespeare supplies clear dysphemisms: Falstaff sneers at conscripts as “food for powder” in Henry IV, Part 1, and Antony brands Caesar’s killers “these butchers” in Julius Caesar.

In Bleak House (1853), Charles Dickens saturates his portrayal of the Court of Chancery with dysphemism. Instead of calling it a court, he brands it a “monstrous maze.” Dickens strips away any semblance of dignity from the system by likening Chancery to a “scarecrow of a suit” and calling its practitioners “vultures.”

Each of these choices substitutes what could have been neutral terms such as “case” or “lawyers” with imagery that dehumanizes and derides. By loading his prose with such dysphemisms, Dickens ensures that the Court of Chancery appears not as a pillar of justice but as a compromised organism feeding on those caught in its endless procedures.

Further Reading

Dysphemism on Wikipedia

Not Nice and Too Nice: A Collection of Dysphemisms and Euphemisms by Merriam-Webster