The term “elision” (from Latin ēlīsiō, meaning “striking out”) refers to the omission of one or more sounds (a vowel, a consonant, or even a full syllable) in speech. In phonetics and linguistics, elision often describes how everyday speech trims weaker or redundant sounds to ease articulation or improve fluency. Because it overlaps with (but is broader than) contraction, many examples of elision are familiar: don’t from “do not,” I’m from “I am,” or gonna from “going to.”

Below, we explore the mechanisms and patterns of elision, survey illustrative elision examples, and discuss its role in English pronunciation, connected speech, and poetry.

Types and Mechanisms of Elision

Vowel Elision and Schwa-Elision

In English, the most common elisions involve weak, unstressed vowels—especially schwa (/ə/)—disappearing between consonants or before certain liquids and nasals. For instance, the vowel in “camera” is often elided in fast speech, yielding something like /ˈkæmrə/ rather than /ˈkæmərə/. Similarly, “history” may reduce from /ˈhɪstəri/ to /ˈhɪstri/ or even /ˈhɪʃri/. In words like “family,” “separate,” and “opera,” the weak vowel may be dropped entirely or replaced by a syllabic consonant (e.g. /ˈfæmli/ vs. /ˈfæməli/).

This process often depends on speech rate, speaker style, and phonetic environment: the more rapid or casual the speech, the more likely elision becomes.

Consonant Elision (Especially /t/ and /d/)

Another frequent pattern is dropping /t/ or /d/ when they occur between consonants or in clusters, particularly when adjacent to other consonants. For example, in “first light,” the /t/ of first may be omitted in rapid speech, effectively rendering something like firs’ light. In phrases like “left the party” or “cold shoulder,” the /t/ or /d/ can vanish: left the → /lef ðə/, cold shoulder → /koʊl ʃoʊldər/ (losing the /d/).

Consonant elision does not always apply mechanically—some phonetic environments prevent it (for example, when /h/ intervenes) or in slower, more careful speech.

Elision in Connected Speech and Sandhi Phenomena

Elision often operates across word boundaries as part of connected speech phenomena. The drive toward smoother, more efficient articulation leads speakers to drop or merge intervening sounds. For instance, “must be” may be realized as /mʌsbi/ or “didn’t he” as /dɪdni/ or /dɪdnʔi/. Words like “give me” → /gɪmi/, “friendly” → /frɛnli/ serve as popular examples. Because elision is context-sensitive, it interacts with other connected-speech processes like assimilation, liaison, and reduction.

Elision Examples and Environments

Here, we present illustrative elision examples (grouped by context) and analyze how they conform to phonetic patterns.

Contractions and Colloquial Speech

Contractions constitute a subclass of elision in which words fuse and one or more sounds are dropped. Common cases include “isn’t” (is not), “I’ve” (I have), “they’d” (they had/should), “I’m” (I am). In many of these, the dropped sound is a vowel or the reduction of a syllable (e.g. “they had” → they’d). Some elisions fall outside strict contraction: gonna for “going to,” kinda for “kind of,” dunno for “don’t know.”

Word-Internal Reduction

Many elision examples appear within individual words, especially in fast or casual speech. Words like “temperature” often lose an unstressed vowel: /ˈtɛmprətʃər/ → /ˈtɛmptʃər/ or /ˈtɛmptʃr/. “History” may become /ˈhɪstri/, “family” → /ˈfæmli/, “camera” → /ˈkæmrə/. These examples show how internal elision reduces syllabic burden when vowels carry weak stress or occur in complex clusters.

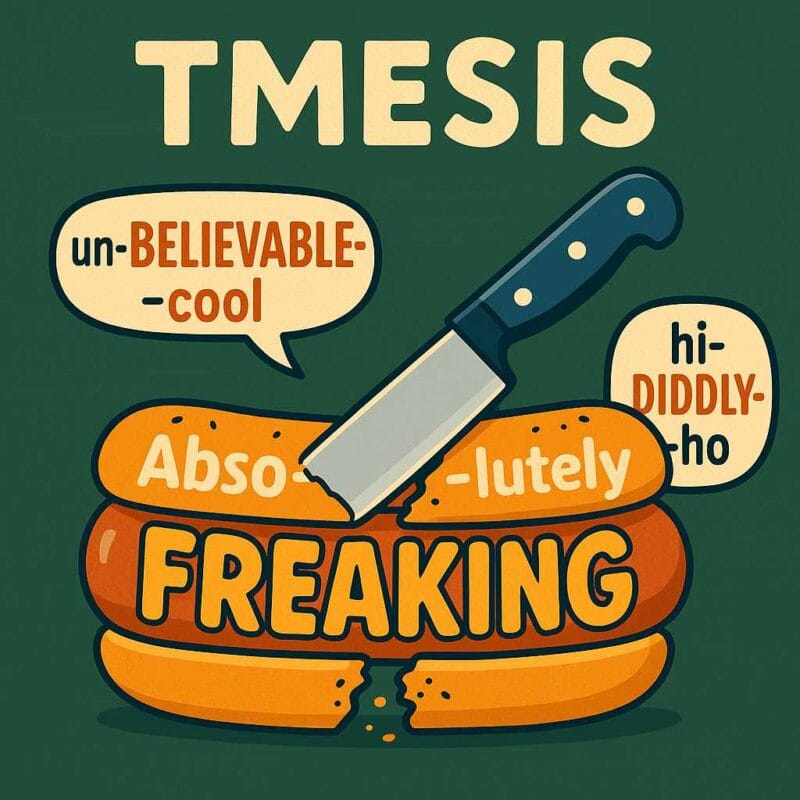

Poetic Elision (Meter, Verse)

In poetry, elision adjusts syllable counts to satisfy meter. A vowel ending a word may be dropped when the next word begins with a vowel or weak consonant—heav’n instead of “heaven,” o’er instead of “over.” Classical Greek and Latin verse followed systematic elision rules; English poets adopted similar devices (e.g. th’angel for “the angel”). Robert Bridges, in his prosocial analysis of Milton, categorized many forms of poetic elision (vowel, R-elision, semi-vowel, etc.) to justify metrical consistency in Paradise Lost (1667).

Impact, Constraints, and Perception

- Efficiency and the principle of least effort: Elision aligns with a principle of articulatory economy: speakers commonly omit sounds that do not impair intelligibility to streamline speech. Over time, repeated elision may stabilize into normative pronunciation, as in “cupboard” (where the /p/ was historically lost) or “Wednesday” (often reduced in casual usage).

- Limits on elision: intelligibility, style, and register: Not every sound is eligible for elision. Phonological constraints (e.g. maintaining minimal contrast), speaker clarity, and the formality of context often prevent elision. In formal or slow speech, speakers may restore elided elements for precision. Moreover, excessive elision can obscure meaning; listeners depend on cues such as context or word boundaries for comprehension.

- Accent, dialect, and perception of fluency: Different accents and dialects use elision to different extents. For example, British English may more readily drop /t/ in “got to” (go’ to) than more enunciated American variants. Non-native speakers who master elision patterns often sound more fluent and natural, but mis-applied elisions may appear sloppy or accented.

Beyond English: Cross-Language Perspectives

While this article emphasizes English, elision is cross-linguistic and interacts with poetic, phonological, and orthographic systems. In French, final e often elides before vowels or mute h, signaled in writing with apostrophes (e.g. l’homme, c’est); classical Latin poetry elided vowels or -m at word boundaries in metrical scansion. Some languages mark elision orthographically, while others treat it purely as a phonetic phenomenon. Recognizing the broader phenomenon clarifies how elision functions in diverse settings.

Strategies for Learners: Recognizing and Practicing Elision

Learners wishing to internalize elision should:

- Listen to natural, connected speech (podcasts, dialogues) and note reduced forms such as gonna, kinda, gimme (/gɪmi/).

- Use phonetic transcripts (e.g. in dictionaries) to spot schwa elision or dropped /t/ in colloquial speech.

- Practice imitating reduced forms in controlled exercises (e.g. “I don’t know” → /aɪ duno/) before gradually inserting them in casual speech.

- Always balance clarity: when meaning may suffer, consciously avoid elision in formal or unfamiliar contexts.

By attending to both the mechanics and stylistic constraints of elision, curious learners deepen their perception of spoken English and sharpen their phonetic intuition.

Further Reading

What Is Elision? Examples in Language and Literature by Kate Miller-Wilson, YourDictionary

Mastering English Language Elisions: How to Sound Like a Native Speaker by Betül Dağ, Lingo Pie

Elision in Spoken English on Reddit

Elision Pronunciation – How to Understand Fast English Speakers by Oxford Online English, YouTube