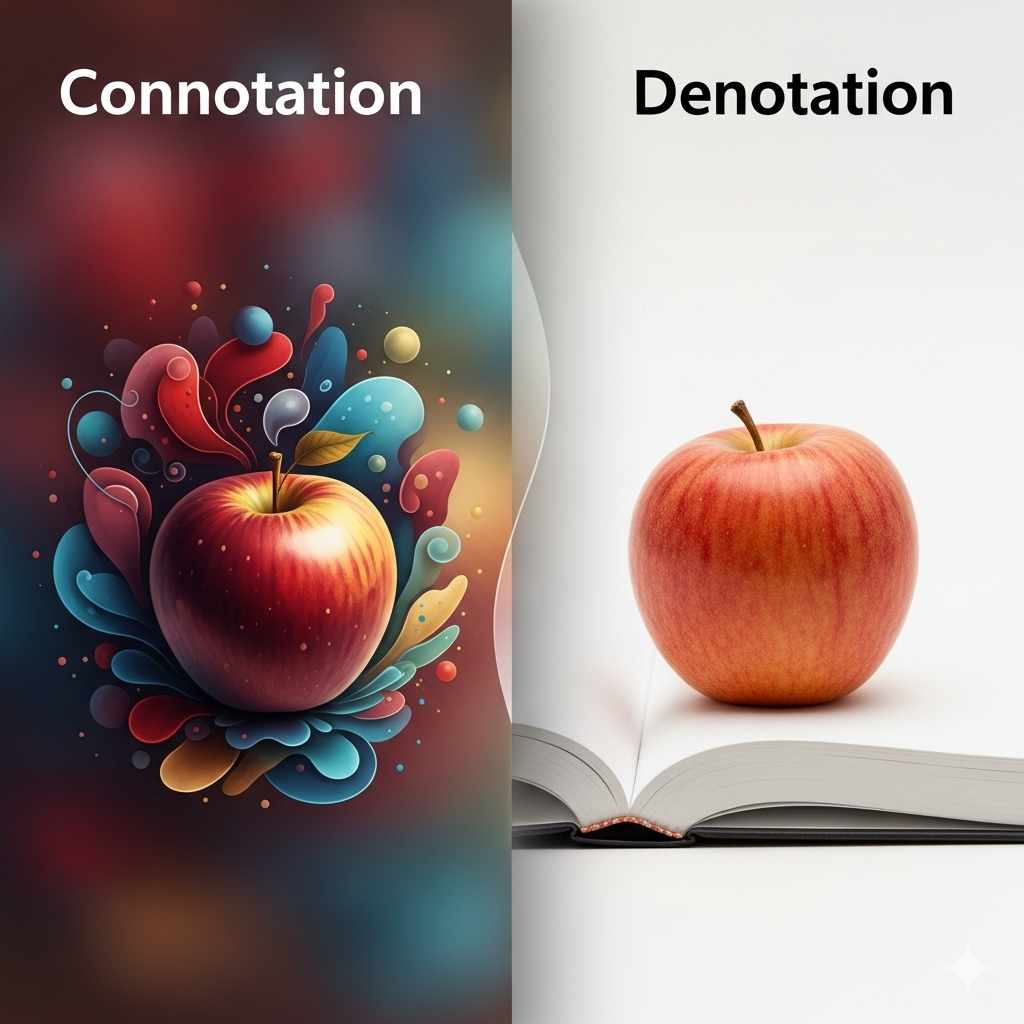

The distinction between connotation and denotation lies at the heart of how words operate in language. In literary writing, their interplay influences atmosphere and texture. Denotation conveys the literal, dictionary meaning of a word, stripped of context or affect. Connotation, by contrast, points to the cultural and emotional associations that cluster around a word.

Both dimensions work together in every expression, but in fiction, the way they are balanced can guide tone and mood with great precision. Writers who recognize this dual role of language can harness it to enrich their prose, moving beyond straightforward description into writing that feels charged with implication.

Denotation: The Ground of Literal Meaning

Denotation provides the stable foundation of language. Without agreed-upon definitions, words would lose their ability to communicate ideas. When a novelist writes “river,” the denotative meaning directs us to a natural stream of water flowing within defined banks. The literal sense carries precision and ensures the reader understands the physical reference.

In scientific writing or legal documents, denotation is paramount because clarity outweighs emotional suggestion. Even in fiction, denotation matters: Ernest Hemingway’s concise style often relied on denotative clarity to portray landscapes, objects, and actions with exactness. Yet if fiction were built solely on denotation, it would lack the suggestive power that makes language reverberate with nuance.

Connotation: The Shade of Suggestion

Connotation expands a word beyond its bare definition. When a character describes a house as a “home,” the shift activates a range of associations, such as warmth, belonging, or intimacy, that the neutral term “house” lacks. Connotation harnesses culture, history, and personal memory.

In William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury (1929), the repeated references to the perishing Compson household carry connotations of deterioration, loss, and the end of a Southern order. Such associations deepen the emotional charge without needing explicit explanation. Connotation thrives on suggestion, operating in the gaps where language meets cultural impact.

The Importance of Connotation in Literature

Writers rarely rely on denotation alone because fiction depends on emotional engagement and atmosphere. Connotation defines characterization and theme as much as imagery. A villain described as “serpentine” draws power not only from the denotative reference to a snake but also from connotative associations of danger, deceit, and temptation rooted in myth and religion.

Poets in particular lean heavily on connotation to compress significance into a few words. Emily Dickinson’s use of “slant” in her poem “Tell all the truth but tell it slant” (1868) derives its impact from connotation by suggesting indirectness, subtlety, and perhaps distortion, all carried by a single word.

More Examples in Fiction

Examples from canonical texts reveal how writers manipulate connotation to expand meaning:

- In George Orwell’s 1984 (1949), the name of the totalitarian figure “Big Brother” carries a denotation of familial closeness while connoting surveillance, intrusion, and authoritarian control.

- In F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925), the word “green” in the famous green light denotes a color but connotes longing, wealth, envy, and unattainable dreams.

- In Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987), the repeated reference to “rememory” invents a denotation through neologism while connoting trauma, haunting, and the persistence of the past.

Denotation also has literary potency when carefully employed. Below are some well-known examples:

- In Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1869), the detailed descriptions of battles rely on the denotative precision of military terms, ensuring clarity in the midst of sprawling events.

- In Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse (1927), the literal description of the sea, waves, and lighthouse establishes a concrete world in which connotative layers about time, distance, and desire can emerge.

The power of denotation lies in its ability to ground the fictional world so that metaphor, symbolism, and association do not drift into vagueness.

How Writers Use Them in Fictional Narratives

Writers employ both dimensions strategically to build character, setting, and theme. Connotation guides emotional coloring by steering the reader’s response without overt direction. Denotation, on the other hand, anchors the scene. It ensures the writer does not lose clarity within suggestion. Successful fiction balances these elements.

- For character creation, connotative choices determines how a figure is perceived: calling a man “gaunt” rather than “thin” draws out connotations of suffering and severity.

- For setting, connotation transforms description into atmosphere: describing fog as “choking” rather than “dense” shifts tone from neutral to oppressive.

- For theme, denotation lays the groundwork for shared reference, while connotation opens interpretive pathways that expand significance.

Great stylists move seamlessly between the two, calibrating precision and suggestion to serve narrative design.

The Role of Figurative Language

Figurative devices such as metaphor, simile, and symbolism rely heavily on connotation. When Sylvia Plath in Ariel (1965) likens herself to a horse rider charging into the morning, the denotative elements (horse, rider, morning) are clear, yet the connotations of freedom, power, and transformation drive the poem’s intensity.

Fictional narratives similarly exploit the connotative charge of figurative language to reach beyond description and establish themes. Denotation ensures the metaphor remains anchored to recognizable references, but connotation carries the emotional and interpretive resonance.

Balancing Precision and Suggestion

The craft of literary writing lies in balancing denotation and connotation rather than privileging one over the other. Writers who ignore denotation risk obscurity; those who neglect connotation produce prose that feels mechanical. The balance can shift depending on genre and purpose.

Science fiction often leans on denotation to describe technological detail, yet its impact depends on the connotative aura of its invented terms. Historical fiction grounds itself in denotative accuracy of place and custom, while relying on connotative language to reanimate vanished worlds. To master the difference between connotation and denotation is to master the spectrum of language, from literal meaning to evocative suggestion.

Further Reading

Connotation vs. Denotation: Literally, what do you mean? by Merriam-Webster

Difference between “connotation” and “denotation”? on Reddit

What is the difference between connotation, annotation, and denotation? on Quora

Connotative vs Denotative by Communication Coach Alexander Lyon, Youtube